Explore the samurai code of Bushido and the ritual suicide of Seppuku (Harakiri). Understand Bushido's core tenets—like righteousness, courage, and loyalty—and its evolution. Learn why samurai performed Seppuku, the different types, and the ritual itself. This guide clarifies the relationship between Bushido and Seppuku, dispelling common misconceptions.

1. Bushido The Way of the Warrior

Bushido, often translated as "the way of the warrior," was the moral code of the samurai, Japan's warrior class, from the 12th to the 19th century. It wasn't a codified set of rules like a legal system, but rather an evolving set of principles, ideals, and ethical guidelines influenced by various philosophical and religious schools of thought, including Zen Buddhism, Confucianism, and Shinto.

1.1 Origins and Development of Bushido

The development of Bushido spanned centuries, influenced by the realities of warfare and the socio-political landscape of Japan. Early samurai culture emphasized martial prowess and loyalty to one's lord. Over time, philosophical and ethical dimensions were integrated, leading to the more complex understanding of Bushido that we recognize today.

Several key periods shaped its evolution:

- Early feudal period (12th-14th centuries): Emphasis on martial skills and loyalty in the midst of constant warfare.

- Sengoku period (15th-17th centuries): A period of intense civil war further emphasized military virtues, but also saw the influence of Zen Buddhism promoting discipline and self-control.

- Edo period (17th-19th centuries): A period of relative peace allowed for the formalization and intellectualization of Bushido through writings like the Hagakure and the Book of Five Rings. This era saw a greater focus on moral and ethical development.

1.2 Key Principles of Bushido

While different schools and individuals emphasized varying aspects, several core principles are generally considered central to Bushido:

| Virtue | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gi (義) | Righteousness, Justice | Doing what is right, even at personal cost. A samurai was expected to uphold a strong sense of justice and fairness. |

| Yu (勇) | Courage, Bravery | Facing danger and adversity with fortitude. Courage was not simply physical bravery, but also the moral courage to stand up for what is right. |

| Jin (仁) | Benevolence, Compassion | Showing kindness and empathy to others. Despite their warrior status, samurai were expected to be compassionate and caring. |

| Rei (礼) | Respect, Courtesy | Demonstrating proper etiquette and respect, even to enemies. Politeness and decorum were highly valued in samurai culture. |

| Makoto (誠) | Honesty, Sincerity | Being truthful and genuine in word and deed. A samurai's word was considered their bond. |

| Meiyo (名誉) | Honor, Glory | Maintaining one's reputation and upholding the samurai code. Honor was paramount, and a samurai would go to great lengths to preserve it. |

| Chu (忠) | Loyalty, Duty | Unwavering devotion to one's lord and fulfilling one's obligations. Loyalty was the cornerstone of the samurai code. |

1.3 Bushido in Modern Japan

Although the samurai class was officially abolished in the late 19th century, the ideals of Bushido continue to resonate in Japanese culture. Concepts like honor, duty, and self-discipline still hold value, influencing various aspects of Japanese society, from business practices to martial arts.

While its influence is debated, Bushido remains a significant part of Japan's historical and cultural legacy, offering insights into the values and beliefs that shaped the samurai and, to some extent, continue to shape Japan today.

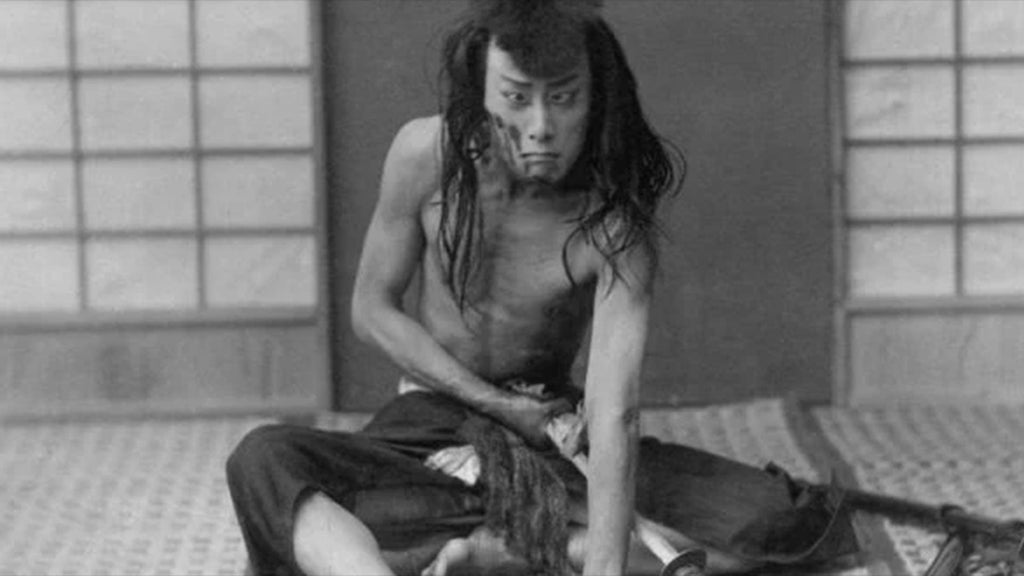

2. Seppuku/Harakiri: Ritual Suicide in Samurai Culture

2.1 Defining Seppuku and Harakiri

While often used interchangeably, seppuku and harakiri have slightly different connotations. Seppuku, written with characters meaning "belly-cutting," is the more formal and ritually significant term, often associated with the samurai class. Harakiri, written with the same characters reversed, is considered a more colloquial term. In essence, seppuku emphasizes the ritualistic and spiritual aspects of the act, while harakiri refers more directly to the physical act of disembowelment.

2.2 Reasons for Seppuku

Seppuku was performed for a variety of reasons, each carrying different levels of hararitual significance and social acceptance:

2.2.1 Junshi: Following One's Lord in Death

Junshi, meaning "following one's lord in death," was practiced by loyal retainers to demonstrate their devotion and to continue serving their lord in the afterlife. This practice, while initially voluntary, became increasingly coerced and was eventually banned during the Edo period.

2.2.2 Kanshi: Death by Protest

Kanshi, or remonstration death, was a form of protest against the actions of a superior, typically a lord or the shogun. By committing seppuku, a samurai could express his disapproval and bring attention to injustice without resorting to direct rebellion.

2.2.3 Funshi: Death to Avoid Capture

Funshi was performed to avoid capture by the enemy, preserving one's honor and preventing the possibility of being tortured or forced to betray one's comrades. It was seen as a way to maintain control over one's destiny in the face of defeat.

2.2.4 Seppuku for Atonement

Seppuku could also be performed as a form of atonement for a grave offense or failure. This act demonstrated remorse and a willingness to accept responsibility for one's actions, potentially mitigating the dishonor brought upon oneself and one's family.

2.3 The Ritual of Seppuku

Seppuku was a highly ritualized act, often performed in the presence of witnesses. The samurai would typically be dressed in white robes, symbolizing purity, and would compose a death poem before the act. He would then make a small cut across his abdomen, followed by a deeper, more decisive cut, often in a left-to-right motion.

2.3.1 The Role of the Kaishakunin

The kaishakunin, a trusted friend or fellow samurai, played a crucial role in the ritual. Their duty was to deliver a swift decapitating blow (kaishaku), immediately after the initial cut, to shorten the samurai's suffering and ensure a quick and honorable death. This act required great skill and precision, as a poorly executed kaishaku could add to the suffering and diminish the honor of the ritual. The relationship between the samurai performing seppuku and the kaishakunin was one of deep trust and respect.

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Junshi | Following one's lord in death |

| Kanshi | Death by protest |

| Funshi | Death to avoid capture |

| Seppuku | Ritual suicide by disembowelment |

| Harakiri | Colloquial term for seppuku |

| Kaishakunin | The individual who performs kaishaku |

| Kaishaku | Decapitation performed during seppuku |

3. Misconceptions and Popular Culture

While bushido and seppuku (harakiri) are significant aspects of Japanese history and culture, they are often romanticized, misinterpreted, or exaggerated in popular culture. This section aims to clarify some common misconceptions.

3.1 The Romanticized Samurai

Movies, books, and video games frequently portray samurai as noble warriors adhering strictly to the bushido code. While bushido undoubtedly influenced samurai behavior, the reality was more complex. Not all samurai were paragons of virtue, and historical accounts reveal instances of betrayal, greed, and cruelty among them. The romanticized image often overlooks the fact that samurai were also a warrior class enforcing the will of the ruling elite, sometimes through brutal means.

3.2 Seppuku as a Common Practice

Popular culture often depicts seppuku as a widespread, almost casual practice among samurai. In reality, while ritual suicide held a significant place in samurai culture, it wasn't as common as often portrayed. It was a highly ritualized act reserved for specific circumstances, and not all samurai performed it throughout their lives.

3.3 The Role of Women

The role of women in samurai culture is often overlooked or minimized. While bushido primarily focused on male warriors, women belonging to samurai families were expected to uphold similar values of honor, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. In some cases, women also committed jigai, a form of ritual suicide distinct from seppuku, often to protect their honor or follow their husbands in death.

3.4 The "Last Samurai" Myth

The concept of the "last samurai" often romanticizes figures like Saigō Takamori, portraying them as tragic heroes clinging to a dying way of life. This narrative often simplifies the complex socio-political changes occurring during the Meiji Restoration, overlooking the diverse motivations and perspectives involved in this period of transformation.

3.5 Bushido and Modern Japan

While formal bushido is no longer practiced, some of its core values, such as honor, discipline, and loyalty, continue to resonate within Japanese society. However, it's crucial to understand the difference between historical bushido and its modern interpretations, which are often adapted and reinterpreted to fit contemporary contexts.

| Misconception | Reality |

|---|---|

| All samurai strictly adhered to bushido. | Bushido influenced samurai behavior, but historical accounts reveal deviations from the ideal. |

| Seppuku was a common practice. | Seppuku was a ritualized act reserved for specific circumstances. |

| Women played a minimal role in samurai culture. | Samurai women were expected to uphold values of honor, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. |

| "Last samurai" narratives accurately depict the Meiji Restoration. | These narratives often simplify the complex socio-political changes of the era. |

4. Summary

This guide has explored bushido, the samurai code, and seppuku (harakiri), ritual suicide, offering a comprehensive overview of their historical context, key principles, and cultural significance. By understanding the nuances of these concepts, we can move beyond popular culture portrayals and appreciate the complexities of samurai history and its enduring legacy in Japan.

5. Summary

This guide has explored the intricate relationship between Bushido, the samurai code, and seppuku (also known as harakiri), a form of ritual suicide practiced within that culture. We've examined the core tenets of Bushido, from its origins to its lasting impact on modern Japan. Furthermore, we delved into the various reasons for seppuku and the specific rituals involved, including the role of the kaishakunin.

| Concept | Key Aspects |

|---|---|

| Bushido (The Way of the Warrior) |

|

| Seppuku (Harakiri) |

|

Understanding the historical context of Bushido and seppuku is crucial to avoiding common misconceptions perpetuated by popular culture. While often romanticized or misinterpreted, these practices offer valuable insights into the complex values and societal pressures of feudal Japan. By examining both Bushido and seppuku, we gain a deeper appreciation for the samurai's unwavering dedication to their code, even in the face of death.

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Related Articles

Leave a comment: