Discover Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo's samurai philosophy. This article illuminates its core Bushido principles, including the "Way of Death," historical context, and enduring relevance for modern life.

1. The Essence of Hagakure Unveiled

1.1 What is Hagakure

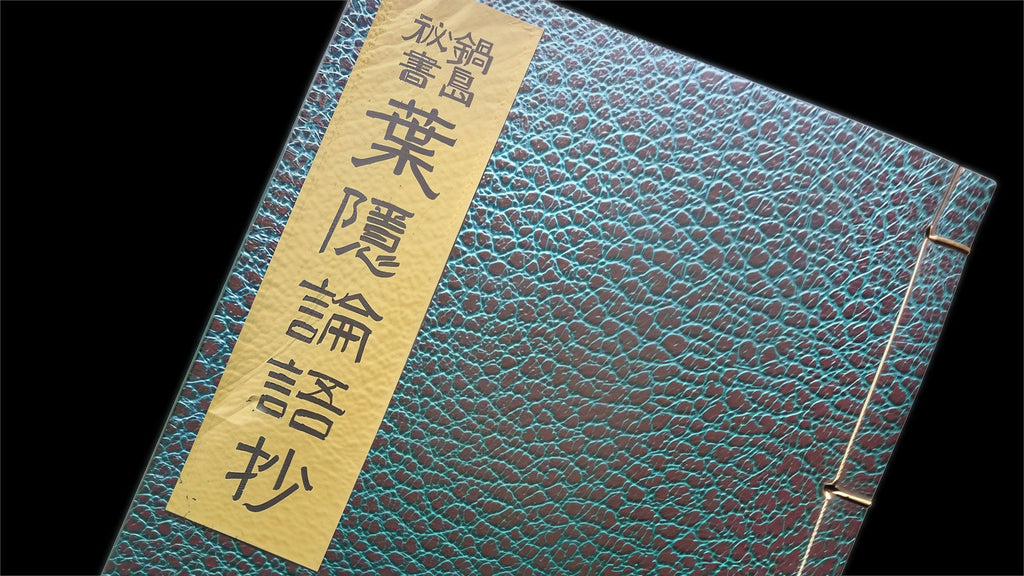

Hagakure, meaning "In the Shadow of Leaves" or "Hidden Leaves," is not a formal philosophical treatise but a profound collection of thoughts, anecdotes, and practical advice on the samurai way of life. Dictated between 1710 and 1716 by the retired samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo to his disciple Tashiro Tsuramoto, it offers a unique and often provocative insight into the Bushido, or the Way of the Warrior, during a period of prolonged peace in Japan.

At its core, Hagakure emphasizes a radical preparedness for death as the ultimate expression of a samurai's loyalty and commitment. It delves into the virtues deemed essential for a warrior, including unwavering loyalty to one's lord, honor, integrity, and the importance of daily discipline in both martial arts and personal conduct. While often associated with a rigid and even fatalistic outlook, the text also explores themes of sincerity, purity of heart, and the constant striving for self-perfection. It serves as a powerful testament to a samurai's dedication, reflecting the values and anxieties of its time.

1.1.1 Key Characteristics of Hagakure

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Nature of Text | A collection of dictated reflections, anecdotes, and advice, rather than a structured philosophical work. |

| Author | Yamamoto Tsunetomo, a retired samurai of the Nabeshima Domain. |

| Compiler | Tashiro Tsuramoto (Tsunetomo's disciple), who transcribed Tsunetomo's oral teachings. |

| Core Theme | The "Way of Death" (Shido), emphasizing preparedness for death as the ultimate form of loyalty and living fully. |

| Key Virtues | Loyalty, honor, duty, sincerity, integrity, martial discipline, and self-sacrifice. |

| Historical Context | Edo Period, a time of peace and perceived decline of the traditional warrior ethos. |

1.2 Yamamoto Tsunetomo The Author

The voice behind Hagakure is that of Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659–1719), a samurai retainer of the Nabeshima Domain in Hizen Province (modern-day Saga Prefecture). Tsunetomo dedicated his life to serving his lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige. His deep personal loyalty and extensive experience within the samurai class shaped his views expressed in Hagakure.

Upon the death of his lord Mitsushige in 1700, Tsunetomo was prevented from performing junshi (ritual suicide to follow one's lord in death) due to a shogunate ban on the practice. This prohibition, coupled with his lord's personal wishes, led him to retire from service and become a Buddhist monk, taking the tonsure and living in seclusion. It was during this period of reflection and detachment from worldly affairs that he dictated his insights, driven by a profound concern for the perceived decline of traditional samurai values in an increasingly peaceful era. His unique position, living outside the direct daily pressures of samurai service yet deeply steeped in its traditions, allowed him to offer a candid and uncompromising perspective.

1.3 Historical Context The Edo Period and Samurai Decline

Hagakure emerged during the Edo Period (1603–1868), a transformative era in Japanese history characterized by over two centuries of unprecedented peace and stability under the centralized rule of the Tokugawa Shogunate. This long period of peace, while beneficial for national development, presented a profound existential challenge to the samurai class.

Traditionally, samurai were warriors whose primary function was warfare. With the absence of major conflicts, their roles shifted dramatically. They transitioned from battlefields to bureaucratic offices, becoming administrators, scholars, and civil servants. This fundamental change led to a perceived softening of the samurai spirit, with many feeling that the true essence of the warrior was being eroded by comfort and routine.

Tsunetomo's Hagakure can be understood as a direct response to this historical context. It is a lament for the fading warrior ethos and a fervent call to return to what he considered the true, uncompromising path of the samurai. The emphasis on the "Way of Death" was not merely a morbid fascination but a philosophical tool to maintain the warrior's readiness and intensity in an age that no longer demanded constant combat. It was a way to cultivate an inner discipline and resolve, ensuring that even in peace, the samurai remained prepared for any eventuality, embodying the ultimate loyalty and self-sacrifice that defined their historical role. The very act of dictating Hagakure was, in a sense, an act of resistance against the perceived dilution of the samurai identity in a world that no longer required their swords.

1.3.1 Samurai Role Transformation in the Edo Period

| Aspect | Pre-Edo Period (Warring States) | Edo Period (Peace) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Direct military combat, warfare, conquest, defense. | Bureaucratic administration, civil service, scholarly pursuits, policing. |

| Lifestyle | Often nomadic, focused on martial prowess and readiness for battle. | Settled in castle towns, emphasis on social etiquette and intellectual development. |

| Source of Status | Battlefield achievements, military leadership. | Hereditary position, administrative competence, adherence to social norms. |

| Challenges Faced | Survival in constant conflict, securing territory. | Maintaining warrior identity, avoiding moral decay, adapting to peace. |

| Philosophical Response | Practical combat manuals, direct application of Bushido in war. | Texts like Hagakure advocating for an internal, spiritual adherence to the warrior way despite peace. |

2. The Core Philosophy of Bushido and the Way of Death

2.1 Bushido: The Way of the Warrior

While the term "Bushido" (武士道), meaning the Way of the Warrior, encompasses a broad ethical code for samurai, Hagakure offers a distinct and often austere interpretation of this philosophy. Unlike more formal treatises that might focus on martial strategy or governance, Hagakure delves into the inner spiritual and moral landscape of the samurai, emphasizing an unwavering commitment to duty and honor above all else. For Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Bushido was not merely a set of rules but a deeply personal and all-encompassing way of life, especially relevant during the peaceful Edo period when opportunities for battlefield glory were scarce.

In Hagakure, Bushido is less about a codified system and more about a state of mind and a relentless pursuit of perfection in one's conduct. It stresses virtues such as rectitude (Gi), courage (Yu), benevolence (Jin), respect (Rei), honesty (Makoto), honor (Meiyo), and above all, unwavering loyalty (Chugi) to one's lord. However, these virtues are often presented through the unique lens of Hagakure's most famous and central teaching: the acceptance and embrace of death.

The text suggests that true Bushido manifests not in grand gestures but in the meticulous attention to daily discipline, sincerity, and the constant preparedness for one's inevitable end. This perspective allowed the samurai to maintain their warrior spirit and integrity even in an era of peace, transforming their inner lives into a battlefield for moral and spiritual victory.

2.2 The Centrality of Death in Hagakure

Perhaps the most famous and often misunderstood aspect of Hagakure's philosophy is its explicit focus on death. The very first line of the text declares: "I have found that the Way of the Warrior is death." This statement is not a morbid fascination with dying, nor is it a simple endorsement of suicide. Instead, it is a profound philosophical stance intended to guide the samurai's entire existence.

For Tsunetomo, the constant awareness of one's mortality serves as a powerful catalyst for living a truly meaningful and effective life. By acknowledging and accepting death as an ever-present possibility, the samurai is meant to be freed from hesitation, fear, and attachment to worldly comforts, reputation, or even life itself. This detachment allows for absolute purity of purpose and unwavering resolve in fulfilling one's duties.

The centrality of death encourages the warrior to act decisively and without reservation, as if each moment could be their last. It cultivates a sense of urgency and profound appreciation for the present moment, ensuring that every action is undertaken with maximum effort and sincerity. This mindset eliminates the fear of failure or physical harm, enabling the samurai to perform their tasks with ultimate courage and dedication, irrespective of the outcome. It is through this constant readiness for death that a samurai could achieve true loyalty and sincerity, becoming a truly selfless instrument for their lord.

2.3 The Concept of Instant Death

Building upon the centrality of death, Hagakure introduces the concept of "instant death" or "dying in advance." This is not a literal call for immediate self-destruction, but rather a rigorous mental discipline. It posits that a samurai should live as if they are already dead, or metaphorically, that they should die in their mind before any action is taken.

This radical form of detachment aims to strip away all ego, self-preservation instincts, and fear of consequences. If one has already "died," then there is no longer a self to protect, a future to worry about, or a reputation to uphold. This mental state allows the warrior to act with unparalleled decisiveness, purity, and fearlessness. Hesitation, which Tsunetomo viewed as a fatal flaw, is completely eliminated because the outcome of one's actions, including one's own survival, becomes irrelevant.

The concept of instant death ensures that the samurai's loyalty and duty to their lord are absolute and uncompromised. It means that one is prepared to sacrifice everything, including one's life, at any given moment for the sake of their lord or their honor. This extreme readiness for self-sacrifice was seen as the ultimate manifestation of Bushido during a period when the traditional role of the samurai was evolving. It was a means of maintaining the fierce, uncompromising spirit of the warrior even when actual combat was rare, channeling that intensity into daily conduct and unwavering service.

| Aspect of Bushido | General Interpretation | Hagakure's Emphasis through "The Way of Death" |

|---|---|---|

| Loyalty (Chugi) | Devotion and faithfulness to one's lord or clan. | Absolute, unquestioning devotion, achieved by overcoming self-preservation through acceptance of death. |

| Courage (Yu) | Bravery in battle and facing danger without fear. | Fearlessness born from the acceptance of one's own mortality, leading to decisive and unhesitating action. |

| Honor (Meiyo) | Maintaining one's reputation and avoiding shame. | Inner integrity and purity of intent, even if it means sacrificing one's life or public understanding. |

| Rectitude (Gi) | Justice, moral correctness, and right conduct. | Acting decisively and correctly, unburdened by fear of consequences, as one is already "dead." |

| Sincerity (Makoto) | Truthfulness and honesty in words and deeds. | Genuine and unreserved commitment to duty, achieved by eliminating self-serving instincts through mental death. |

3. Key Principles and Teachings

3.1 Loyalty and Duty to One's Lord

At the very heart of Hagakure lies an unwavering emphasis on absolute loyalty and selfless duty to one's lord. Yamamoto Tsunetomo posits that a samurai's existence is fundamentally defined by this devotion, transcending personal desires, family ties, and even life itself. This concept, known as `chūgi` (loyalty), was the bedrock of the feudal system and the samurai's social contract.

Tsunetomo stresses that a samurai should always prioritize the lord's welfare, honor, and prosperity above all else. This isn't merely about obedience but about a profound internal commitment. The ideal samurai is one who is constantly prepared to sacrifice everything for their master, seeing their own life as expendable in the service of their domain. This commitment is often linked to the concept of `on` (a profound debt or obligation) owed to the lord, which can only be repaid through unwavering service and, if necessary, death.

The text suggests that loyalty is not just a public display but a deeply ingrained internal state, manifesting in every action and thought. Even in times of peace, the samurai's mind should be focused on how to best serve and protect their lord, anticipating needs and dangers.

3.2 Honor, Integrity, and Reputation

For the samurai, `meiyo` (honor) was not just a virtue but the very essence of their being. Hagakure meticulously details the paramount importance of maintaining one's honor, integrity, and reputation (`na`). A samurai without honor was considered worse than dead, as it brought shame not only upon themselves but also upon their family, clan, and lord.

Tsunetomo advises that a samurai must always act with the utmost integrity, ensuring their actions align with their principles, even when unobserved. The fear of `haji` (shame or disgrace) was a powerful motivator, driving samurai to uphold stringent codes of conduct. This extended to every aspect of life, from martial prowess to administrative duties, and even personal interactions. A samurai's reputation was their most valuable asset, built on a lifetime of honorable conduct and decisive action.

The text often presents scenarios where a samurai must choose between life and honor, invariably advocating for the latter. This reflects the belief that true existence was tied to the preservation of one's good name, which would endure long after physical death.

3.3 Sincerity and Purity of Heart

Beyond outward displays of loyalty and honor, Hagakure places significant emphasis on `makoto` (sincerity) and `kokoro` (purity of heart or mind). Tsunetomo argues that true samurai conduct stems from an inner state of genuine intent, free from duplicity, calculation, or ulterior motives. It's about acting with a clear, unburdened mind, focused solely on the task at hand and the principles guiding it.

This purity of heart allows a samurai to act decisively and without hesitation, particularly in moments of crisis or when facing death. If one's heart is clouded by attachments, fears, or self-interest, it hinders their ability to fully embody the Way of the Warrior. Sincerity ensures that one's actions are authentic and reflect their true commitment to their lord and their chosen path.

Tsunetomo suggests that by cultivating a sincere and pure heart, a samurai can achieve a state of readiness for anything, including their own demise, without regret or internal conflict. This internal alignment is crucial for living a life consistent with the Way of Death.

3.4 Martial Arts and Practical Conduct

While Hagakure is deeply philosophical, it never loses sight of the practical realities of a samurai's life, including the mastery of martial arts and disciplined daily conduct. Tsunetomo emphasizes that the Way of the Warrior is not merely a theoretical construct but must be lived out through constant training and readiness.

The text frequently references the importance of sword practice (`kenjutsu`) and other martial skills, not just for combat effectiveness but as a means of cultivating discipline, focus, and an immediate connection to the reality of death. The idea of the "one cut" or `itto` — the ability to resolve a situation with a single, decisive action — underscores the need for absolute proficiency and mental clarity.

However, practical conduct extends beyond the battlefield. It encompasses the samurai's demeanor, speech, and interactions in everyday life. Every action, no matter how mundane, is an opportunity to embody the principles of Bushido. This includes punctuality, politeness, attention to detail, and maintaining a composed bearing under all circumstances. For Tsunetomo, the Way is found in the everyday details, and consistent, disciplined conduct is the manifestation of a samurai's inner commitment.

3.5 The Importance of Daily Discipline

Yamamoto Tsunetomo places immense value on `shugyo` (austere training or discipline) as an ongoing, lifelong process. He argues that the Way of the Warrior is not something achieved through a single grand gesture but through consistent, diligent effort in daily life. This daily discipline is the foundation upon which a samurai builds their character, skills, and readiness for death.

This involves not only martial training but also mental and spiritual cultivation. It includes rigorous self-examination, adherence to routines, and the cultivation of virtues like patience, perseverance, and humility. Tsunetomo advocates for a constant state of preparedness, where the samurai is always mindful of their mortality and ready to face any challenge, including death, at a moment's notice.

The table below summarizes some of the key aspects of daily discipline emphasized in Hagakure:

| Aspect of Discipline | Description in Hagakure | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Constant Readiness | Always being prepared for battle or death, physically and mentally. | To ensure no hesitation or regret when the decisive moment arrives. |

| Mindfulness in Routine | Performing even mundane tasks with full attention and sincerity. | To cultivate focus, presence, and embody the Way in all actions. |

| Self-Correction | Regularly reflecting on one's actions and thoughts to improve. | To eliminate flaws, cultivate virtues, and maintain purity of heart. |

| Cultivation of Skills | Continuous practice of martial arts and other necessary abilities. | To ensure proficiency, confidence, and decisive action when needed. |

| Maintaining Appearance | Attention to personal grooming and attire, even in private. | To reflect inner discipline and readiness, honoring one's status. |

Through such consistent discipline, a samurai develops an unbreakable spirit and a profound understanding that the Way is lived in every moment, not just in extraordinary circumstances.

4. Yamamoto Tsunetomo A Life of Dedication

4.1 Tsunetomo's Background and Service

Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659–1719) was a samurai of the Nabeshima clan, a prominent domain in what is now Saga Prefecture. Born into a distinguished samurai family, Tsunetomo began his service at a young age, entering the employ of Nabeshima Mitsushige, the third lord of the Nabeshima domain, at the age of nine. His life was characterized by unwavering loyalty and diligent service to his lord for over three decades.

During his tenure, Tsunetomo served in various capacities, including as a chamberlain and attendant, gaining intimate knowledge of the domain's affairs and the intricacies of samurai life. His devotion to Lord Mitsushige was absolute, forming the bedrock of his personal philosophy and later, the essence of Hagakure. Tsunetomo's service spanned a period of relative peace under the Tokugawa shogunate, a time when the practical warrior skills of the samurai were slowly giving way to more bureaucratic and administrative roles. This shift significantly influenced his perspective on the declining samurai spirit, a central theme in his teachings.

Upon the death of his lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige, in 1700, Tsunetomo faced a profound personal crisis. Customarily, a loyal retainer would follow their lord in death through ritual suicide, known as junshi (殉死). However, Lord Mitsushige himself had forbidden junshi for his retainers, following a shogunate decree that aimed to curb such practices. This prohibition left Tsunetomo in a difficult position, forcing him to reconcile his deep-seated desire to follow his lord with the explicit command not to do so. This pivotal event led to his retirement from active service and his decision to become a Buddhist monk, adopting the monastic name Jocho.

4.2 The Motivation Behind Hagakure's Creation

After his retirement and entry into monastic life, Yamamoto Tsunetomo retreated to a hermitage outside Saga Castle. It was during this period, from 1710 to 1716, that he engaged in conversations with a young samurai scribe named Tashiro Tsuramoto. Tsunetomo, now in his fifties, felt a profound sense of urgency to transmit the values and spirit of the samurai way as he understood it, believing them to be rapidly eroding in the peaceful Edo period.

His motivation was multi-faceted:

- Preservation of the Old Ways: Tsunetomo lamented what he perceived as a decline in the true samurai spirit, a shift from martial valor and selfless loyalty to more materialistic and bureaucratic concerns. He sought to preserve the essence of the samurai's moral and ethical code for future generations.

- Guidance for Future Samurai: He believed that the younger samurai of his time lacked the authentic understanding of Bushido that had guided his own life. Hagakure was intended as a practical guide, offering insights into conduct, duty, and the mindset required for a samurai.

- Personal Reflection and Legacy: The dictation process also served as a means for Tsunetomo to reflect on his own life, his service, and the lessons he had learned. It was his way of leaving a lasting legacy, not just for his clan but for the samurai class as a whole.

The core of his message was a radical emphasis on the readiness to die at any moment, which he believed was the ultimate expression of loyalty and freedom from worldly attachments. This philosophy was a direct response to the perceived complacency of an era without major warfare.

4.3 Jocho Yamamoto Tsunetomo's Disciple

The creation of Hagakure was not a solitary endeavor but a collaborative effort between Yamamoto Tsunetomo and his devoted scribe, Tashiro Tsuramoto (田代陣基, 1678–1748). While Tsunetomo adopted the monastic name Jocho, it is Tsuramoto who diligently recorded Tsunetomo's sayings and reflections over a period of seven years.

Tashiro Tsuramoto was a young samurai of the Nabeshima clan who, like Tsunetomo, was deeply concerned about the changing times and the erosion of traditional samurai values. He visited Tsunetomo at his hermitage, engaging in extensive conversations that covered a vast range of topics: samurai ethics, practical conduct, historical anecdotes, and personal observations. Tsuramoto's role was not merely that of a transcriber; he was an active listener and questioner, prompting Tsunetomo to elaborate on his ideas and ensuring the comprehensive recording of his master's thoughts.

The resulting compilation, originally titled Nabeshima Rongo (The Analects of Nabeshima) and later known as Hagakure, was initially kept within the Nabeshima clan and circulated only among a select few. It was a private collection of wisdom, not intended for public dissemination, which explains its candid and sometimes provocative nature.

The relationship between Tsunetomo and Tsuramoto was one of master and disciple, built on mutual respect and a shared commitment to the ideals of Bushido. Tsuramoto's dedication ensured that Tsunetomo's profound insights and experiences were preserved, allowing Hagakure to eventually emerge as one of the most influential texts on samurai philosophy.

4.3.1 Key Figures in Hagakure's Creation

| Figure | Role | Contribution to Hagakure |

|---|---|---|

| Yamamoto Tsunetomo (Jocho) | Author/Dictator | The primary source of the philosophy and anecdotes; dictated his life's wisdom and observations. |

| Tashiro Tsuramoto | Disciple/Scribe | Diligently recorded and compiled Tsunetomo's oral teachings over seven years, forming the text of Hagakure. |

| Nabeshima Mitsushige | Lord | Tsunetomo's revered lord; his death and the prohibition of junshi were pivotal events leading to Tsunetomo's retirement and the creation of the text. |

5. Misinterpretations and Controversies

5.1 The Allegation of Fanaticism

Hagakure, while revered by many, has also faced significant criticism, primarily centered on the perception of it promoting a fanatic adherence to death and blind obedience. This interpretation often stems from the text's famous opening line: "I have found that the Way of the Warrior is death." Critics argue that this phrase, taken in isolation, suggests a reckless pursuit of death or a nihilistic outlook, leading to a misunderstanding of its deeper philosophical underpinnings. However, proponents argue that this "way of death" is not about dying carelessly, but rather about a profound readiness to die, which paradoxically frees the samurai to live fully and act decisively without fear or hesitation. It is about transcending the fear of death to achieve ultimate sincerity and effectiveness in one's duties. The text emphasizes that such a mindset allows a warrior to remain true to their lord and their principles, even in the face of insurmountable odds, embodying a state of ultimate commitment rather than a desire for self-destruction. The alleged fanaticism often overlooks the extensive practical advice, emphasis on daily discipline, and the pursuit of sincerity that permeates the work.

5.2 Hagakure's Role in World War II Japan

Perhaps the most significant and controversial period for Hagakure was its resurgence and deliberate promotion during World War II in Japan. During this time, the text was selectively interpreted and propagated by militarist regimes to foster extreme nationalism, unwavering loyalty to the Emperor, and a willingness for ultimate self-sacrifice among soldiers and the populace. The nuanced teachings of Yamamoto Tsunetomo, originally intended for a specific feudal context during a time of peace, were distorted to serve a wartime agenda. The concept of "instant death" was stripped of its spiritual and ethical context and weaponized to encourage kamikaze pilots and suicidal charges, transforming a philosophy of personal integrity and readiness for duty into a tool for state-sanctioned fanaticism. The original text's emphasis on individual sincerity and the moral integrity of the samurai within their domain was largely ignored in favor of a narrative that demanded unquestioning obedience and sacrifice for the nation. This appropriation led to a post-war backlash, where Hagakure was often viewed with suspicion and associated with the militaristic excesses of the era.

| Aspect | Original Context (Edo Period) | Wartime Interpretation (WWII) |

|---|---|---|

| "Way of Death" | A philosophical readiness to die, enabling sincere action and duty fulfillment without hesitation. Freedom from fear of death to live fully. | A literal command for self-sacrifice and suicide missions (e.g., kamikaze), promoting blind obedience and nationalistic fanaticism. |

| Loyalty | Deep, personal loyalty to one's feudal lord (daimyo) and domain, rooted in sincerity and duty. | Absolute, unquestioning loyalty to the Emperor and the state, used to justify expansionism and war. |

| Purpose | Guidance for personal conduct, moral integrity, and maintaining the samurai spirit during a time of peace. | Propaganda tool to instill extreme militarism, suppress dissent, and encourage ultimate sacrifice for the war effort. |

| Focus | Individual samurai's inner state, discipline, and ethical conduct within a specific feudal structure. | Collective nationalistic fervor, martial spirit, and sacrifice for the imperial agenda. |

5.3 Critiques and Modern Perspectives

Beyond the WWII controversy, Hagakure has faced various critiques from scholars and modern readers. Some argue that its teachings are anachronistic and incompatible with contemporary values, promoting a rigid hierarchy and a mindset that could stifle individuality or critical thought. Critics point to the seemingly extreme emphasis on loyalty and the acceptance of death as potentially fostering a cult of personality or blind obedience rather than fostering independent moral reasoning. Additionally, the text's often raw and unrefined nature, being a collection of oral teachings, can make it challenging to interpret consistently, leading to varied and sometimes contradictory understandings.

However, modern perspectives increasingly seek to extract universal wisdom from Hagakure while acknowledging its historical context. Many scholars and practitioners now view it not as a literal guide for modern life, but as a profound exploration of human nature, discipline, and commitment. They emphasize aspects like sincerity, resilience, mindfulness, and the importance of living fully in the present moment, detached from the fear of future outcomes. This approach allows readers to appreciate Tsunetomo's insights into self-mastery and ethical conduct, separating them from the feudalistic or militaristic interpretations that have historically clouded its reception. The ongoing dialogue surrounding Hagakure highlights its enduring power to provoke thought and inspire debate on the nature of duty, honor, and human existence.

6. Hagakure's Enduring Relevance Today

While written centuries ago for a specific warrior class in feudal Japan, the profound philosophical underpinnings of Hagakure transcend its historical context. Its teachings offer surprising and valuable insights applicable to modern life, leadership, personal development, and even contemporary psychological practices.

6.1 Lessons for Leadership and Business

The principles espoused in Hagakure, particularly those concerning loyalty, duty, decisive action, and unwavering commitment, resonate strongly within today's competitive business and leadership landscapes. Though the context has shifted from lord and samurai to CEO and employee, or leader and team, the core tenets remain potent:

- Decisive Action and Risk-Taking: The samurai's readiness for "instant death" can be reinterpreted as a call for leaders to make bold, timely decisions without excessive hesitation, understanding the potential consequences but not being paralyzed by them. This fosters agility and responsiveness in dynamic markets.

- Unwavering Loyalty and Commitment: While not advocating blind obedience, Hagakure emphasizes deep loyalty to one's organization or mission. For modern businesses, this translates to fostering a culture of commitment, where employees are invested in the company's success and uphold its values.

- Integrity and Reputation: The samurai's profound concern for honor and reputation translates directly to the importance of ethical conduct and building trust in business. A leader's integrity is paramount for inspiring confidence and maintaining a positive corporate image.

- Service and Selflessness: The warrior's dedication to serving their lord, often above personal gain, can be adapted to a leadership style focused on serving the team, customers, and the broader organizational goals. This selfless approach builds stronger teams and fosters a more positive work environment.

- Continuous Self-Improvement: The samurai's constant training and pursuit of martial excellence reflect the modern business imperative for continuous learning, skill development, and adapting to new challenges.

6.2 Personal Growth and Resilience

Hagakure offers a rigorous framework for cultivating inner strength and resilience in the face of life's inevitable challenges. Its emphasis on mental fortitude and preparation for adversity provides a unique perspective on personal development:

- Embracing Adversity: The philosophy encourages individuals to confront difficulties head-on, viewing challenges not as obstacles but as opportunities for growth and to demonstrate one's character. This mindset is crucial for building psychological resilience.

- Self-Discipline and Purpose: The rigorous daily discipline advocated for samurai can be applied to personal goals, fostering habits that lead to self-mastery and a purposeful existence. Living with a clear sense of duty and intention can provide direction and meaning.

- Cultivating Inner Calm: Despite its focus on death, Hagakure implicitly promotes a profound inner calm derived from accepting one's mortality and focusing on what is within one's control. This equanimity allows individuals to navigate stress and uncertainty with greater composure.

- Living Authentically: The emphasis on sincerity and purity of heart encourages individuals to align their actions with their true values, fostering authenticity and integrity in all aspects of life.

6.3 Mindfulness and Living in the Present

Paradoxically, Hagakure's preoccupation with death leads to a profound appreciation for life and the present moment. The concept of "instant death" can be interpreted not as a morbid obsession, but as a catalyst for heightened awareness and full engagement with the here and now:

- Full Engagement in Every Task: If one is always prepared for the end, then every action, no matter how mundane, is performed with utmost seriousness and dedication. This mirrors modern mindfulness practices that encourage full presence in daily activities, from drinking tea to performing complex tasks.

- Awareness of Impermanence: The constant awareness of mortality, a central theme in Hagakure, serves as a powerful reminder of life's fleeting nature. This awareness can deepen appreciation for experiences, relationships, and the preciousness of each moment, preventing procrastination and fostering a sense of urgency to live fully.

- Letting Go of Attachments: The samurai's readiness to die implies a detachment from outcomes and material possessions. This detachment, when applied to modern life, can reduce anxiety and stress, allowing for greater freedom and peace of mind, aligning with principles of non-attachment found in various Eastern philosophies.

6.4 Stoicism and Eastern Philosophy Parallels

The philosophical underpinnings of Hagakure share striking similarities with Western Stoicism and other Eastern philosophical traditions, highlighting universal human concerns and wisdom:

| Principle / Concept | Hagakure (Samurai Philosophy) | Stoicism (Western Philosophy) | Zen Buddhism (Eastern Philosophy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance of Fate / Impermanence | "The Way of the Warrior is to find death." Embracing mortality and the unpredictable nature of life. | "Amor Fati" (Love of Fate). Accepting what is beyond one's control, including death and misfortune. | "Anicca" (Impermanence). Understanding that all phenomena are constantly changing and impermanent. |

| Focus on Virtue / Inner Character | Emphasis on honor, loyalty, integrity, sincerity, and courage as paramount virtues. | Virtue is the sole good. Cultivating wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance as the highest aim. | Emphasis on compassion, mindfulness, and the development of an enlightened mind. |

| Discipline / Training | Rigorous martial and moral training, daily practice, and self-control. | Practical exercises and mental disciplines to cultivate resilience and rational thought. | Meditation (Zazen), mindfulness, and adherence to precepts to achieve enlightenment. |

| Action / Duty | Immediate action and unwavering commitment to one's duty and lord. | Focus on acting virtuously in the world and fulfilling one's role in society. | Right action and skillful means, performing tasks with full awareness. |

| Detachment from Outcomes | Readiness to die implies detachment from life's comforts and outcomes. | Focus on effort and intention, not on external results, which are outside one's control. | Non-attachment to desires and outcomes as a path to reduce suffering. |

These parallels underscore Hagakure's position not merely as a historical document, but as a work of profound philosophical depth that continues to offer valuable guidance for navigating the complexities of human existence.

7. Accessing Hagakure Notable Translations

For those seeking to delve into the profound teachings of Hagakure, understanding the various available translations is crucial. As a classical Japanese text penned in the early 18th century, its nuances, historical context, and philosophical depth require skilled interpretation. Different translators bring unique perspectives, academic rigor, and literary styles, each offering a distinct gateway into Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s world.

7.1 William Scott Wilson's Translation

One of the most widely recognized and influential translations of Hagakure is by William Scott Wilson, titled "Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai." Published by Kodansha International, Wilson's work has long been a staple for English-speaking readers interested in samurai philosophy and martial arts. Wilson, a respected scholar of Japanese literature and martial arts, is known for his ability to capture the poetic and spiritual essence of classical texts.

- Approach and Style: Wilson's translation is often praised for its readability and its focus on conveying the inherent spirit and philosophical weight of Tsunetomo's words. He tends to emphasize the martial and spiritual dimensions, making it particularly appealing to practitioners of traditional Japanese arts and those interested in the more esoteric aspects of Bushido.

- Completeness: This edition offers a substantial portion of the original text, presenting a comprehensive view of Tsunetomo's teachings, though not every single passage from the extensive original eleven books.

- Strengths: Readers often find Wilson's prose to be elegant and evocative, providing a compelling and immersive experience. His deep understanding of the historical context and the nuances of samurai culture shines through, offering a translation that feels authentic to the period and captures the aesthetic qualities of the text.

7.2 Alexander Bennett's Translation

More recently, Alexander Bennett's translation, also titled "Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai" (Tuttle Publishing, 2010), and his later "The Complete Hagakure" (Tuttle Publishing, 2019), have gained significant acclaim. Bennett is a highly regarded academic and practitioner of Japanese martial arts, holding a high rank in Kendo. His background provides a unique blend of scholarly precision and practical insight into the Way of the Warrior.

- Approach and Style: Bennett's translations are characterized by their academic rigor, meticulous research, and comprehensive annotations. He strives for a high degree of literal accuracy while ensuring accessibility for a modern audience. His editions often include extensive introductions, historical context, and detailed footnotes that clarify obscure references and provide deeper understanding of the philosophical underpinnings.

- Completeness: "The Complete Hagakure" is particularly notable for being the first full, unabridged English translation of all eleven books of the original text, including sections previously omitted or abridged in other editions. This makes it an invaluable resource for scholars and serious students.

- Strengths: Bennett's work is invaluable for serious students and scholars who require a more detailed and contextually rich understanding of Hagakure. His clear, precise language and thorough explanations help to demystify complex concepts and address potential misinterpretations that have arisen over time regarding Tsunetomo's philosophy.

7.3 Other Editions and Interpretations

While Wilson and Bennett's translations are currently the most prominent, other editions and interpretations of Hagakure have existed over time, each contributing to its accessibility and understanding:

- Paul Gordon Smith's "Hagakure: The Way of the Samurai" (1999) was an earlier significant attempt to bring Tsunetomo's work to a wider audience, focusing on selected passages. While not a complete translation, it served as an important introduction for many readers.

-

Challenges in Translation: Translating classical Japanese philosophical texts like Hagakure presents inherent challenges. The original text is a collection of dictated anecdotes and musings, not a formally structured treatise. Its language is dense, often elliptical, and deeply embedded in the specific cultural and linguistic context of the Edo period. Translators must grapple with:

- Idiomatic Expressions: Many phrases do not have direct English equivalents, requiring careful interpretation.

- Cultural Nuances: Concepts like 'Bushido' or 'honor' carry specific weight in Japanese culture that can be difficult to fully convey across linguistic and cultural divides.

- Ambiguity: Tsunetomo's often stark and seemingly contradictory statements require careful interpretation to avoid misrepresenting his core message, especially his famous emphasis on "instant death."

- The Value of Comparison: For a truly comprehensive understanding, readers are often encouraged to consult multiple translations. Comparing how different scholars interpret the same passages can illuminate various facets of Tsunetomo's philosophy and provide a richer, more nuanced appreciation of Hagakure's enduring wisdom, highlighting both the consistencies and subtle differences in interpretation.

7.3.1 Comparison of Notable Translations

| Feature | William Scott Wilson's "Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai" | Alexander Bennett's "Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai" / "The Complete Hagakure" |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Poetic, spiritual, and martial essence, emphasizing readability and flow. | Academic rigor, historical context, and comprehensive detail, with extensive annotations. |

| Style | Flowing, evocative, literary, aiming to capture the aesthetic and philosophical spirit. | Clear, precise, scholarly, and annotated, prioritizing accuracy and contextual clarity. |

| Completeness | Substantial selection of the original text, providing a comprehensive overview of key teachings. | "The Complete Hagakure" is the first full, unabridged English translation of all eleven books, including previously omitted sections. |

| Target Audience | Martial artists, general readers seeking philosophical insights, those appreciating a more literary and spiritual approach to the text. | Scholars, serious students, readers seeking deep contextual understanding, and those valuing academic precision and thoroughness. |

| Strengths | Captures the spirit and mood of the original, offers an accessible and engaging reading experience, and conveys the martial arts philosophy effectively. | Accuracy, extensive notes, detailed historical background, comprehensive coverage of the entire work, and addresses common misinterpretations of Hagakure. |

8. Comparing Hagakure with Other Samurai Texts

8.1 Hagakure Versus Miyamoto Musashi's Book of Five Rings

While both Hagakure and Miyamoto Musashi's The Book of Five Rings (Go Rin No Sho) are foundational texts for understanding the samurai ethos, they originate from distinct perspectives and offer different lessons. Hagakure, penned by Yamamoto Tsunetomo in the early 18th century, reflects the perspective of a retainer in a period of relative peace, emphasizing a spiritual and ethical readiness for death and unwavering loyalty. In contrast, The Book of Five Rings, written by the legendary swordsman Miyamoto Musashi in the mid-17th century, is a practical treatise on martial strategy, swordsmanship, and tactical thinking derived from a life spent in duels and battles.

The core distinction lies in their primary focus: Hagakure is largely a guide to the inner life of a samurai, stressing **the spiritual preparation for death** and the cultivation of an unwavering spirit of loyalty and duty. It delves into the samurai's daily conduct, moral integrity, and the purity of their intentions. Musashi's work, however, is a strategic manual, dissecting the art of combat, the psychology of an opponent, and the principles of victory in real-world engagements. It is less about the philosophical 'Way of Death' and more about the practical 'Way of Victory'.

Consider their approaches to training: Hagakure advocates for constant self-discipline and mental preparedness, viewing every moment as an opportunity to cultivate the samurai spirit. Musashi, while also emphasizing rigorous training, focuses on the physical and strategic mastery of the sword, advocating for **fluidity, adaptability, and understanding the rhythm of combat**. Their audiences also differed; Hagakure was a private record for a specific clan, intended to preserve a fading samurai spirit, while Musashi's work was a broader treatise on strategy applicable not only to swordsmanship but also to various aspects of life and leadership.

| Feature | Hagakure (Yamamoto Tsunetomo) | The Book of Five Rings (Miyamoto Musashi) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Spiritual and ethical readiness, loyalty, the "Way of Death" | Practical martial strategy, swordsmanship, tactical victory |

| Historical Context | Edo Period peace (early 18th century), preservation of samurai ideals | Sengoku/early Edo Period (mid-17th century), direct combat experience |

| Key Message | **Embrace death to live fully and serve loyally** | **Master strategy to achieve victory in all aspects of life** |

| Emphasis | Inner discipline, moral purity, unwavering resolve | Practical application, adaptability, psychological advantage |

| Audience/Purpose | Private record for a specific clan, preserving fading samurai spirit | Broader treatise on strategy for martial artists and leaders |

8.2 Zen Buddhism and the Samurai Way

Zen Buddhism profoundly influenced the development of Bushido, the Way of the Warrior, and its principles are deeply interwoven into many samurai texts, including Hagakure. Zen offered the samurai a philosophical framework for **facing death with equanimity**, cultivating mental fortitude, and achieving a state of "no-mind" (mushin) essential for spontaneous and effective action in combat. Concepts like impermanence (mujo), detachment, and living in the present moment resonated strongly with the samurai's perilous existence.

In Hagakure, the Zen influence is particularly evident in its emphasis on **detachment from the outcome of actions** and the acceptance of death as an ever-present reality. The famous phrase "The Way of the Warrior is death" reflects a Zen-like acceptance of impermanence, suggesting that by constantly contemplating death, a samurai could live more fully and act without hesitation. This contemplation was not morbid but a means to achieve ultimate freedom and effectiveness. The text encourages a state of mind where one is always prepared to die, thus removing fear and enabling decisive action. This aligns with Zen's focus on **direct experience and intuitive action** over intellectualization or hesitation.

Furthermore, Hagakure's advocacy for **daily discipline and mindfulness** in every task, no matter how mundane, mirrors Zen monastic practices. The idea that one should perform even the simplest duties with the same focus and dedication as facing an enemy in battle echoes Zen's emphasis on bringing complete awareness to every moment. While Hagakure does not explicitly discuss Zen meditation techniques, its underlying philosophy encourages a similar mental state of focused presence and unshakeable calm, which are hallmarks of Zen training. However, it's worth noting that Hagakure's interpretation of these Zen principles is often filtered through a lens of absolute loyalty and a more rigid adherence to duty than some other Zen-influenced samurai texts might present, which might emphasize individual enlightenment more broadly.

8.3 Confucianism's Influence on Bushido

Confucianism, introduced to Japan centuries before the Edo period, played a significant role in shaping the social and ethical fabric of samurai society and the broader concept of Bushido. Its emphasis on **hierarchy, loyalty to one's lord, filial piety, benevolence, righteousness, and propriety** provided a structured moral framework that complemented the martial aspects of the samurai way. Many samurai texts and codes of conduct drew heavily from Confucian principles to establish social order and define the samurai's responsibilities.

Hagakure, while deeply rooted in the samurai tradition, presents a complex relationship with Confucianism. On one hand, it strongly upholds the Confucian virtue of loyalty (chu) to one's lord, elevating it to an absolute and unquestionable principle. The entire text is essentially a testament to unwavering service and devotion. The importance of sincerity (makoto) and integrity, also prominent in Hagakure, aligns with Confucian ideals of moral uprightness.

However, Hagakure also notably **diverges from strict Confucian rationality** in its extreme emphasis on the "Way of Death." Confucianism typically prioritizes rational governance, social harmony, and the preservation of life and order. Yamamoto Tsunetomo's radical assertion that "The Way of the Warrior is death" and his encouragement of impulsive, decisive action even to the point of self-sacrifice, can be seen as a departure from the more balanced and pragmatic approach often found in Confucian thought. While Confucianism values loyalty, it usually within a framework that considers the larger societal good and the preservation of the ruling house, often through strategic, calculated means. Hagakure, by contrast, seems to advocate for a more immediate and less calculating form of devotion, sometimes even bordering on fanaticism from a purely Confucian viewpoint.

In other samurai texts or historical periods, Confucianism might have led to a more bureaucratic and less individually radical interpretation of loyalty, emphasizing the samurai's role as administrators and moral exemplars within a stable social structure. Hagakure, written during a time when the samurai's traditional martial role was diminishing, sought to re-instill a primal, uncompromising spirit that transcended the more measured and rationalistic aspects of Confucianism, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable devotion and preparedness for ultimate sacrifice.

9. Summary

Hagakure, meaning "In the Shadow of Leaves," stands as a seminal work of samurai philosophy, offering profound insights into the ethos of the warrior class during Japan's Edo Period. Compiled in the early 18th century by Tsunetomo's disciple, Tashiro Tsuramoto, from the oral teachings of Yamamoto Tsunetomo, a former samurai retainer of the Nabeshima domain, this text serves as a poignant reflection on a fading way of life.

At its heart, Hagakure articulates a unique interpretation of Bushido, "the Way of the Warrior," emphasizing an unwavering commitment to one's lord and an acute awareness of mortality. Unlike other samurai texts that might focus on martial strategy or Zen enlightenment, Tsunetomo's philosophy is famously encapsulated in the phrase, "the Way of the Warrior is death." This concept is not a call for reckless self-destruction, but rather a profound mental preparedness to accept death at any moment, thereby enabling one to live fully and act decisively without hesitation, a principle often referred to as "instant death."

The text delves into a myriad of practical and ethical guidelines for samurai conduct, stressing virtues such as absolute loyalty, unblemished honor, integrity, sincerity, and purity of heart. It champions daily discipline, not just in martial arts but in every aspect of life, urging the samurai to constantly refine their character and fulfill their duties with utmost dedication. Tsunetomo's teachings were born from a sense of crisis, as the long period of peace under the Tokugawa Shogunate saw the samurai's traditional role diminish, leading him to advocate for a return to the rigorous, self-sacrificing spirit he believed was being lost.

Despite its profound philosophical depth, Hagakure has faced its share of misinterpretations and controversies. Its stark emphasis on death and duty has led some to criticize it as promoting fanaticism or blind obedience. Notably, its selective adoption during World War II Japan, where certain passages were used to fuel ultranationalist fervor, further complicated its legacy. However, modern scholarship often contextualizes these interpretations, distinguishing Tsunetomo's original intent from later political appropriations.

Today, Hagakure's relevance extends far beyond its historical context. Its principles offer valuable lessons for leadership and business, emphasizing decisive action, accountability, and the importance of a strong ethical foundation. For personal growth, it inspires resilience, mindfulness, and living authentically in the present moment, echoing parallels found in Western philosophies like Stoicism.

Accessing Hagakure has been made possible through various notable translations, including those by William Scott Wilson and Alexander Bennett, each offering unique insights into the nuances of Tsunetomo's original Japanese.

While often compared to other seminal samurai texts like Miyamoto Musashi's "Book of Five Rings," Hagakure distinguishes itself by focusing less on strategy and more on the inner spiritual and moral disposition of the warrior. Its unique blend of Zen Buddhist and Confucian influences, filtered through Tsunetomo's personal experience, provides a distinct perspective on Bushido.

In essence, Hagakure remains a powerful and challenging text that invites readers to confront fundamental questions about life, death, duty, and honor. It is not merely a historical artifact but a living philosophy that continues to provoke thought and inspire individuals seeking a path of integrity and purpose in a complex world.

9.1 Key Distinctions of Hagakure's Philosophy

| Aspect | Hagakure's Emphasis | Contrast with General Bushido / Other Texts |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | "The Way of the Warrior is death." A constant readiness to die, enabling fearless action and living fully. | Other texts (e.g., Musashi) often focus on winning, martial skill, or strategic mastery. |

| Motivation for Writing | A lament for the perceived decline of the samurai spirit during a period of peace (Edo Period). | Many samurai texts were written as practical guides for combat or governance during war. |

| Loyalty | Absolute, unwavering loyalty to one's lord, even in the face of death or apparent futility. | While loyalty is central to Bushido, Hagakure's portrayal is particularly intense and personal. |

| Practicality vs. Spirit | Strong emphasis on the inner spiritual state, moral purity, and mental preparedness over mere physical skill. | "Book of Five Rings" focuses heavily on practical combat techniques and strategy. |

| Sincerity & Purity | Advocates for a deep, unadulterated sincerity in all actions and intentions, free from calculation. | While important, not always articulated with the same fervent emphasis as in Hagakure. |

| Historical Context | A product of a time when the samurai's traditional role was changing, leading to a nostalgic and urgent call for adherence to old ways. | Many Bushido texts emerged during periods of active warfare, reflecting different practical concerns. |

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Related Articles

Leave a comment: