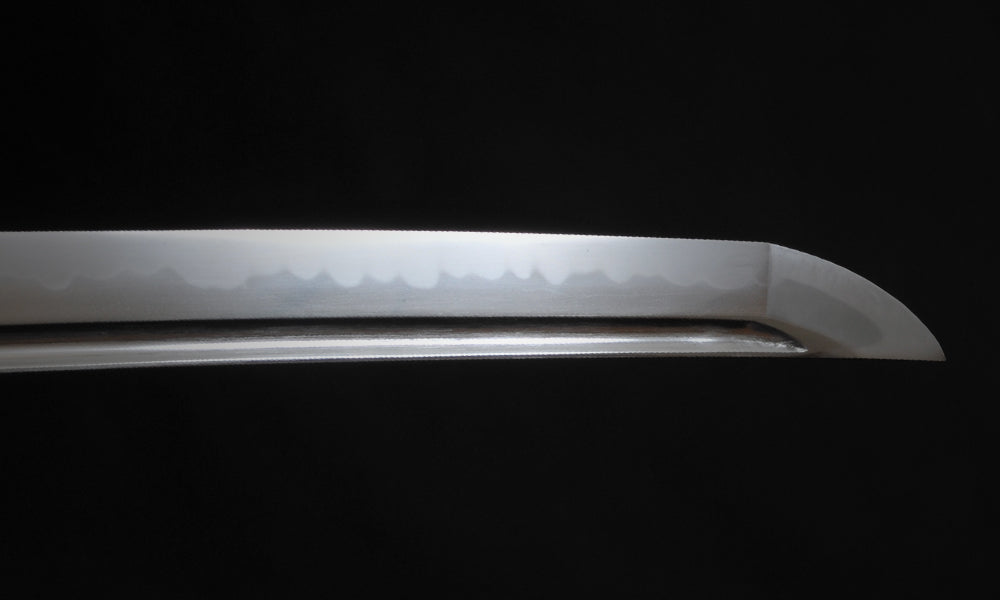

The blade of the Japanese sword is made by heating the tamahagane (steel for making swords) to high temperature then hitting it flat with a mallet. They use a chisel to create the rift in the blades, fold it, then hit it again with a mallet. This process is repeated over and over again. This is called tanren, which also means “training” in Japanese. This results in a distinct pattern appearing in the hiraji and shinogiji. This pattern is called kitae-hada(literally means forged and folded surfaces) or kitae.

Kitae-hada

The tanren methods differ between the era and school of swordsmiths which gives different appearances and is a key point in determining the style of swords in during authentication. When the kitae-hada appears clearly on the blade, they say “Hada ga tatsu”, meaning the surface stands out.. When it appears meticulous on the blade they say “the skin is fine”. Here I will introduce some typical kitae-hada in categories. However, many swords have a kitae-hada of multiple categories, and this fusion is what creates the complexity and beauty of the sword patterns.

Mokume (Wood Grain)

This looks like the annual ring of the tree. There are no wood grain patterns alone but present among cross grains or mixed together. If there is an abundance of wood grains overall, it is called “mokume”. It is common in swords made in Bizen (Okayama) in ancient times.

Itame (Wood Slab Grain)

This pattern resembles the patterns of wooden boards, and it is the most common pattern found among all Japanese swords old and new. It is further divided into size and how it appears. The bigger ones are called “o-itame” and the more intricate ones “ko-itame”. O-itame is found commonly among the Soshu (Kanagawa) schools.

Masame (Straight Grain)

Like the straight grain of wood, this pattern has multiple lines running along the blade. This is common among the Yamato (Nara) swordsmiths, and it is said that the Yamato swords always include masame somewhere in the sword.

Ayasugi (Wave)

In the pattern, the straight lines become crooked like waves continuously. It looks like the “ayasugi” pattern which is a traditional zig-zag pattern in Japan since old times. It appears commonly in the Gassan swordsmiths in the Tohoku region, giving its alternative name “Gassan-hada”.

Matsukawa (Pine Tree Bark)

This pattern looks like a spot appearing on a big cross-grain pattern, and it looks like a pine tree park. It also looks like hijiki (a type of seaweed) and is also called “hijiki-hada”.

Nashiji (Pear)

It is finely carved that it is very difficult to see it, but there is a strong “boil” pattern there, almost like the skin of a pear. For the older swords, the boils appear strong and abundant, whereas in the new swords the pattern is so fine that it almost appears patternless. It looks beautiful, but often the boils are rough and lack strength.

Konuka (Rice bran)

This is like the nashiji pattern, but with the lack of boils, the pattern looks like white dots. The name was given as it looks like rice brans spread out on a glass board. It is found commonly among the Hizen (Nagazaki) swords during the new sword era, and is also called Hizen-hada.

Summary

There are now two identical kitae-hada, and it is an artistic element that further brings out the charm of the Japanese sword. It is also bears testimony to the Japanese sword which does not bend or break easily and can cut well.

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Leave a comment: