Uncover the unbreakable bond linking the Japanese sword to samurai identity. This piece reveals how the iconic katana was not just a weapon, but the very soul of the warrior, embodying Bushido and shaping their place in society.

1. Introduction The Unbreakable Bond

The Japanese sword, or Nihonto, is far more than a mere weapon; it is a profound symbol, an artistic masterpiece, and a spiritual artifact deeply interwoven with the identity of the samurai, Japan's elite warrior class. This introduction embarks on an exploration of the unbreakable bond between the samurai and their sword, a connection so intrinsic that the blade was often considered the very soul of the warrior. We will delve into how this iconic weapon not only defined the samurai's role in feudal Japan but also served as a mirror to their innermost character, values, and societal standing, ultimately shaping a unique warrior identity that continues to fascinate the world.

1.1 Defining the Samurai and Their Iconic Blade

The samurai, meaning "those who serve," emerged as a powerful military and social class in feudal Japan, adhering to a strict code of conduct and valuing martial prowess above all. Central to their existence and image was the Japanese sword, most famously the katana. This curved, single-edged blade was not merely a tool for warfare; it was the samurai's constant companion, a badge of their rank, and a testament to their dedication to the warrior's path. The relationship was so profound that the samurai and their sword were often seen as an indivisible entity, the blade representing an extension of the warrior's arm and will. The quality and craftsmanship of a sword were paramount, reflecting the status and discernment of its owner. This intimate connection between the warrior and their weapon laid the foundation for an identity built on principles of honor, discipline, and martial excellence.

1.2 The Sword as a Mirror of the Warrior's Soul

In the samurai ethos, the sword was revered as the physical embodiment of the warrior's soul (tamashii). It was believed that the blade possessed its own spirit, reflecting the purity, integrity, and strength of its wielder. A samurai's sword was meticulously cared for, not just for its practical utility in combat, but as a sacred object that mirrored their inner state. A polished, well-kept blade signified a disciplined and honorable samurai, while a neglected one could imply a flaw in character or a departure from the warrior's code. The sword was thus a constant reminder of the virtues a samurai was expected to uphold: courage, loyalty, righteousness, and self-control. This belief elevated the Japanese sword from a simple implement of war to a profound symbol of the samurai's spiritual and moral identity, a true reflection of their inner being.

1.3 Exploring the Concept of Identity in Feudal Japan

Identity in feudal Japan was largely predetermined by birth, social class, and one's designated role within a highly structured, hierarchical society. For the samurai, their identity was inextricably linked to their martial function, their unwavering loyalty to their lord (daimyo), and the strictures of their warrior code. The sword played a crucial role in visibly and symbolically cementing this identity. Possessing and wearing swords, particularly the daisho (pair of long and short swords), was a distinct privilege of the samurai class, instantly distinguishing them from other social strata. This privilege came with immense responsibilities and expectations, shaping every aspect of a samurai's life and conduct.

| Aspect of Feudal Japanese Identity | General Significance | Samurai Context and Sword Linkage |

|---|---|---|

| Social Hierarchy | Society was rigidly stratified, with distinct roles and privileges for each class (e.g., nobility, warriors, farmers, artisans, merchants). | Samurai were near the top, serving as the military and ruling elite. The sword was a clear visual marker of this elevated status. |

| Loyalty (Chugi) | A paramount virtue, especially loyalty to one's superiors and clan. | Central to the samurai code (Bushido). The sword was often pledged in oaths of fealty and used to defend their lord's honor, making it a symbol of unwavering allegiance. |

| Honor (Meiyo) | A deeply ingrained concept, crucial for personal and familial reputation. Loss of honor could be worse than death. | The samurai's honor was intrinsically tied to their actions, martial skill, and their sword. The blade was used to defend personal and clan honor, and in extreme cases, in the ritual of seppuku to preserve it. |

| Role and Duty | Each individual had specific duties and responsibilities based on their position in society. | The samurai's primary role was that of a warrior and protector. Their swords were the tools of their trade and symbols of their martial duty, constantly reminding them of their responsibilities. |

Thus, the Japanese sword was not just an accessory but a cornerstone of samurai identity, representing their authority, their martial skill, their spiritual depth, and their unwavering commitment to a unique way of life that profoundly shaped Japanese history and culture.

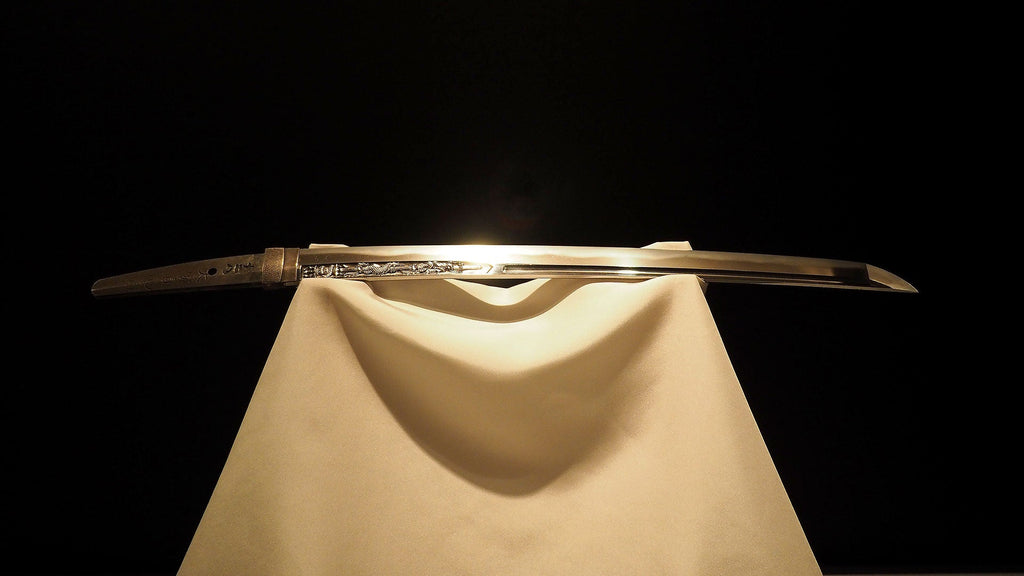

2. The Katana: An Emblem of Perfection and Power

The Katana, with its iconic curved, single-edged blade and long grip for two-handed use, is more than just a weapon; it is a profound symbol of Japanese culture, artistry, and the samurai spirit. Revered for its exceptional cutting ability and aesthetic beauty, the Katana stands as an emblem of the relentless pursuit of perfection and the embodiment of power, both martial and spiritual. Its creation was a sacred act, and its possession a mark of honor and responsibility, deeply intertwined with the identity of the warrior class that wielded it.

2.1 The Art and Mystique of Japanese Swordsmithing

The creation of a Japanese sword, particularly the Katana, is a highly sophisticated and ritualistic process, honed over centuries by master swordsmiths (tosho). This intricate craft, often regarded as a sacred art form, involves not only exceptional technical skill but also profound spiritual dedication. The swordsmith would often undergo purification rituals before commencing work, imbuing the process with a sense of reverence. The forging itself involves repeatedly heating, hammering, and folding the steel, a technique that removes impurities and creates thousands of infinitesimally thin, laminated layers. This meticulous folding results in the characteristic grain pattern (hada) visible on the blade's surface. Following the shaping and folding, the blade undergoes differential hardening. Clay is meticulously applied in a specific pattern along the blade, with a thicker layer on the spine and a thinner layer along the edge. When heated and quenched, the edge cools rapidly, becoming incredibly hard (forming the hamon, or temper line), while the body and spine cool more slowly, retaining a softer, more shock-absorbent quality. This combination gives the Katana its legendary ability to maintain a razor-sharp edge while resisting breakage. The final stages involve meticulous polishing, a painstaking process undertaken by specialized craftsmen (togishi) to bring out the blade's inherent beauty, revealing the hamon and hada, and sharpening the edge to its fearsome potential.

2.1.1 Tamahagane Steel: The Soul of the Sword

At the heart of every traditionally made Japanese sword lies tamahagane, often referred to as "jewel steel." This precious metal is produced in a traditional clay smelting furnace called a tatara, a laborious process lasting several days and nights, fueled by vast quantities of charcoal and iron sand (satetsu). The tatara master carefully controls the temperature and conditions to produce a bloom of steel with varying carbon content. The swordsmith then meticulously selects pieces of tamahagane, breaking them apart and examining the fracture patterns to identify high-carbon steel (kawagane), ideal for the sharp edge, and lower-carbon steel (shingane), which forms the softer, more resilient core of the blade. The purity and unique properties of tamahagane are considered essential for crafting a superior sword, contributing not only to its physical attributes but also to its spiritual essence. Many believe the very soul of the sword originates from this carefully crafted steel, making it far more than mere raw material.

2.1.2 Legendary Swordsmiths: Masamune and Muramasa

Throughout Japanese history, numerous swordsmiths achieved legendary status, but few names resonate as powerfully as Goro Nyudo Masamune and Sengo Muramasa. Masamune (c. 1264–1343 AD), active during the late Kamakura period, is widely regarded as Japan's greatest swordsmith. His blades are celebrated for their ethereal beauty, flawless craftsmanship, and remarkable resilience. Masamune's swords often exhibit a sophisticated nie-deki hamon, characterized by bright, individual martensite crystals, and are associated with a sense of calm, strength, and defensive prowess. Legends often depict his swords as instruments of peace and justice. In contrast, Muramasa (active during the Muromachi period, 14th-16th centuries) forged blades renowned for their extraordinary sharpness and almost unsettling cutting ability. Folklore and popular culture have often imbued Muramasa swords with a bloodthirsty or even cursed nature, supposedly driving their wielders to violence. While historical evidence for such curses is lacking, the reputation reflects the sheer martial effectiveness of his creations. The contrasting legacies of Masamune and Muramasa highlight the diverse qualities valued in Japanese swords and the deep cultural narratives woven around these master craftsmen and their iconic blades.

2.2 Types of Japanese Swords: Beyond the Katana

While the Katana is the most internationally recognized Japanese sword, it is but one of a family of blades, each designed for specific purposes and reflecting different eras of warfare and societal norms. The collective term for these traditional blades is nihonto. Understanding these variations provides a richer appreciation for the evolution of Japanese swordsmanship and samurai culture.

| Feature | Tachi (太刀) | Wakizashi (脇差) | Tanto (短刀) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Cavalry combat, ceremonial display | Auxiliary weapon, indoor combat, symbol of status (as part of daisho) | Close-quarters combat, armor-piercing, ritual suicide (seppuku) |

| Blade Length (Nagasa) | Typically over 60 cm (approx. 23.6 inches), often longer and more curved than Katana | Typically between 30 cm and 60 cm (approx. 11.8 to 23.6 inches) | Typically under 30 cm (approx. 11.8 inches) |

| Curvature (Sori) | Often more pronounced, with the deepest point of curvature (koshi-zori) closer to the hilt | Moderate, similar to Katana | Usually straight (hira-zukuri) or slightly curved (uchizori) |

| Method of Wear | Suspended from the belt with the cutting edge facing down (tachi-koshirae) | Worn thrust through the sash (obi) with the cutting edge facing up, often paired with a Katana (daisho) | Worn thrust through the obi, sometimes concealed |

| Era of Prominence | Predominantly Koto period (pre-1596), especially Heian and Kamakura periods | Muromachi period onwards, solidified as part of the samurai's daisho in the Edo period | Used throughout samurai history, with various styles and applications |

2.2.1 Tachi: The Predecessor on Horseback

The Tachi was the primary sword of the samurai during the Koto period (roughly 900-1596 AD), an era characterized by mounted archery and warfare. Typically longer and more deeply curved than the later Katana, the Tachi was designed for use by cavalry. It was worn slung from the belt with the cutting edge facing downwards, allowing for an efficient draw while on horseback. The curvature and length of the Tachi facilitated sweeping cuts from a mounted position. Many Tachi blades were later shortened and remounted as Katanas when fighting styles shifted towards more ground-based combat.

2.2.2 Wakizashi: The Companion Sword and Symbol of Status

The Wakizashi, or "side inserted [sword]," is a shorter blade, typically ranging from 30 to 60 centimeters. It served as the companion sword to the Katana, and together they formed the daisho ("big-little"), the symbolic pairing that represented a samurai's social status and honor. The Wakizashi was used as an auxiliary weapon in battle, for fighting in confined spaces where the Katana was unwieldy, and sometimes for the gruesome task of beheading a defeated opponent. Samurai would wear the Wakizashi at all times, even indoors where the Katana might be left at the entrance, signifying their constant readiness and warrior identity.

2.2.3 Tanto: The Dagger for Close Quarters and Ritual

The Tanto is a Japanese dagger, with a blade usually less than 30 centimeters long. It was designed primarily as a stabbing weapon but could also be used for slashing in extremely close combat. Some Tanto were specifically designed as yoroi-doshi ("armor piercers"), with thick, strong blades capable of penetrating gaps in samurai armor. Beyond its martial applications, the Tanto held significant ritualistic importance. It was the weapon of choice for ritual suicide (seppuku or hara-kiri) for samurai men, and sometimes for women of the samurai class (jigai) to preserve honor or avoid capture. Various styles of Tanto existed, reflecting different combat needs and aesthetic preferences.

2.3 The Sword's Sacred and Spiritual Significance

In Japanese culture, particularly within Shintoism, objects of exceptional craftsmanship or natural beauty can be seen as housing kami (spirits or deities). The Japanese sword, due to the purity of its materials, the intense spiritual focus of its creation, and its vital role in life and death, was often regarded as a sacred object. Swordsmiths traditionally observed Shinto purification rites before and during the forging process, and shrines were often erected within their forges. Famous swords were sometimes enshrined, given names, and treated with profound respect, almost as living entities. They were considered protectors against evil spirits and symbols of purity and justice. This spiritual dimension elevated the sword beyond a mere tool of war, transforming it into a repository of spiritual power and a tangible link to the divine. The meticulous care and etiquette surrounding the handling and display of swords further underscored their sacred status, reflecting a deep-seated reverence that permeated samurai culture and continues to influence Japanese perspectives on these remarkable blades.

3. The Samurai Rise of a Warrior Ethos

The samurai, Japan's elite warrior class, did not emerge fully formed. Their ascent was a gradual process, deeply intertwined with the evolution of Japanese feudal society and the development of a unique martial and ethical code. This chapter explores the origins of the samurai, the forging of their guiding principles known as Bushido, and their multifaceted role in shaping Japanese history and warfare.

3.1 Origins and Evolution of the Samurai Class

The term "samurai" itself means "those who serve" (from the verb saburau), initially referring to attendants of the nobility. Their journey from provincial guards to the de facto rulers of Japan spanned several centuries, marked by shifting political landscapes and constant martial demands.

- Early Beginnings (Pre-Heian and Heian Period, c. 7th - 12th centuries): The earliest precursors to the samurai were mounted archers and swordsmen employed by the imperial court and powerful clans for protection and military campaigns. During the Heian period (794-1185), the central government's authority weakened in the provinces. This led to the rise of provincial warrior families (bushi), who developed their own power bases, often managing large estates (shoen) and providing military service to absentee aristocrats. Clans like the Taira (Heike) and Minamoto (Genji) became particularly prominent, engaging in fierce rivalries.

- The Kamakura Period (1185-1333): The Genpei War (1180-1185) between the Minamoto and Taira clans culminated in Minamoto no Yoritomo establishing the Kamakura Shogunate (Bakufu) in 1192. This marked a pivotal moment: the samurai class effectively seized political control, with the Shogun as their military dictator. The samurai became the ruling elite, their status solidified by land grants and privileges in exchange for loyalty and military service. The way of the horse and bow, kyuba no michi, was a central tenet of their martial identity during this era.

- The Muromachi Period (1336-1573): This era, including the tumultuous Sengoku Jidai (Warring States period) from the mid-15th to early 17th century, was characterized by near-constant civil war. Regional lords (daimyo) vied for power, leading to an increased demand for skilled samurai. Martial prowess was paramount, and warfare became more sophisticated. It was during this period that the sword began to gain even greater prominence as the primary weapon and symbol of the samurai. Concepts of loyalty were tested and often redefined amidst shifting allegiances.

- Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1568-1600): The efforts of Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu gradually brought an end to the Sengoku Jidai, unifying Japan. Samurai played crucial roles in these unification wars. Hideyoshi's "sword hunt" (katanagari) in 1588 disarmed the peasantry, further cementing the samurai's exclusive right to bear arms and reinforcing their distinct social status.

By the end of these formative centuries, the samurai had evolved from mere servants into a powerful military and political aristocracy, their identity inextricably linked to warfare and governance.

3.2 Bushido The Way of the Warrior

Bushido, literally "the Way of the Warrior," represents the ethical code and moral principles that guided the samurai. It was not initially a written, formalized doctrine but rather an unwritten code of conduct that evolved organically over centuries, shaped by the samurai's experiences in warfare, their social responsibilities, and philosophical influences. While often romanticized, Bushido provided a framework for samurai behavior, emphasizing virtues deemed essential for a warrior's life and death.

3.2.1 Core Tenets Honor Loyalty and Courage

The principles of Bushido, though varying slightly in interpretation and emphasis over time and among different clans, generally revolved around several key virtues. These ideals shaped the samurai's self-perception and their expectations of one another.

| Tenet (Japanese) | English Translation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gi (義) | Rectitude / Justice | The ability to make morally sound decisions and act upon them without hesitation; choosing the right path based on reason and moral principles. It meant upholding what is right and just, even when difficult. |

| Yu (勇) | Courage / Bravery | Heroic valor and bravery in the face of adversity, danger, or death. This courage was not reckless abandon but rather a calm, rational fearlessness rooted in training and conviction. |

| Jin (仁) | Benevolence / Mercy | Compassion, empathy, and kindness towards others, particularly those weaker or defeated. While warriors, samurai were also expected to govern and show concern for the welfare of the people under their protection. |

| Rei (礼) | Respect / Politeness | Proper conduct, courtesy, and adherence to social etiquette and ceremony. Rei demonstrated respect for others, social hierarchy, and tradition, contributing to social harmony. |

| Makoto (誠) or Shin (信) | Honesty / Sincerity | Truthfulness in word and deed; living with utmost integrity. A samurai's word was considered his bond, and sincerity was essential for trust and honor. |

| Meiyo (名誉) | Honor | A profound sense of personal dignity, reputation, and worth. Maintaining one's honor, and that of one's family and lord, was paramount. Shame (haji) was to be avoided at all costs, often leading to extreme measures to preserve or restore honor. |

| Chugi (忠義) or Chu (忠) | Loyalty | Unwavering allegiance, devotion, and faithfulness, primarily to one's feudal lord (daimyo). This was often considered the cornerstone of Bushido, demanding selfless service and sacrifice. |

3.2.2 The Influence of Zen Buddhism and Shintoism

The philosophical underpinnings of Bushido were significantly shaped by Japan's major religious and ethical systems:

- Zen Buddhism: Introduced to Japan from China, Zen had a profound impact on the samurai mindset. Zen Buddhism's emphasis on discipline, self-control, meditation (zazen), and the attainment of a state of "no-mind" (mushin) resonated deeply with the warrior class. Mushin allowed for spontaneous and intuitive action in combat, free from fear or hesitation. Zen also fostered an acceptance of impermanence and death, crucial for warriors constantly facing mortality.

- Shintoism: As Japan's indigenous religion, Shinto instilled a deep reverence for ancestors, nature, and loyalty to the land and its traditions. Concepts of purity, respect for deities (kami), and a connection to the imperial lineage (though often symbolic in terms of direct political power) contributed to the samurai's sense of duty and national identity. Shinto rituals and beliefs were integrated into many aspects of samurai life.

- Confucianism: Though not exclusively a religion, Confucian philosophy, with its emphasis on social order, filial piety, and hierarchical relationships, heavily influenced Bushido. The Confucian stress on loyalty (to one's superior), righteousness, and the proper conduct within social structures provided a framework for the samurai's role in a feudal society and their obligations to their lord and family.

These influences combined to create a complex ethical system that, while not always perfectly adhered to, provided a powerful ideal for the samurai to strive towards, shaping their identity as more than just fighters, but as disciplined, honorable, and loyal members of society.

3.3 The Samurais Role in Japanese Society and Warfare

The samurai were not merely soldiers; they were a distinct social class with wide-ranging responsibilities and influence that evolved over time, particularly with the transition from constant warfare to prolonged peace.

- Military Dominance: The primary function of the samurai was as skilled warriors. Initially, their martial prowess was centered on mounted archery (yabusame) and the use of weapons like the naginata (polearm) and yari (spear). Over time, especially from the Kamakura period onwards, the sword (tachi, then katana) became their signature weapon and symbol. They were masters of various martial arts (bujutsu) and wore distinctive armor (yoroi). Their military role was crucial in both defending and expanding the territories of their lords, and later, in maintaining the Shogun's authority.

- Political and Administrative Authority: With the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate, samurai became the ruling class. High-ranking samurai, or daimyo, controlled vast domains and wielded significant political power. Even lower-ranking samurai often served as administrators, magistrates, and officials within their lord's territory or the shogunate's bureaucracy. During the peaceful Edo period (1603-1868), these administrative roles became even more prominent for many samurai.

- Social Status and Hierarchy: During the Edo period, Japanese society was rigidly structured under the Shi-no-ko-sho social hierarchy (Samurai, Farmers, Artisans, Merchants). The samurai (shi) were at the apex, entitled to privileges such as the right to wear two swords (daisho) and to cut down commoners who disrespected them (kiri-sute gomen, though rarely exercised). This elevated status came with expectations of exemplary conduct and leadership.

- Cultural Patrons and Practitioners: Contrary to the image of being solely rough warriors, many samurai were highly cultured. They patronized and practiced various arts, including Noh theater, the tea ceremony (chanoyu), calligraphy (shodo), poetry (haikai, waka), and ink painting (sumi-e). These pursuits were often seen as complementary to their martial training, fostering discipline, aesthetic sensibility, and mental acuity.

- Guardians of Order and Tradition: As the ruling class, samurai were responsible for maintaining peace and order within society. They enforced laws, resolved disputes, and upheld social norms. Their adherence to Bushido, at least in its idealized form, was meant to set an example for the rest of the populace. The figure of the ronin, or masterless samurai, often highlighted the complexities and challenges of adhering to this ethos outside the established feudal structure.

The samurai's multifaceted role as warriors, leaders, administrators, and cultural figures was central to the fabric of feudal Japan. Their ethos, though evolving, provided a guiding compass for their actions and profoundly shaped their collective identity and the course of Japanese history.

4. Forging Identity The Sword as the Samurai's Soul

The Japanese sword, particularly the katana, was far more than a mere weapon for the samurai; it was an extension of his being, a physical manifestation of his honor, and the ultimate symbol of his unique identity within feudal Japanese society. This chapter delves into the profound connection between the samurai and his blade, exploring how the sword was not just carried, but lived, shaping the warrior's perception of himself and his role in the world. The very act of forging a sword was imbued with Shinto rituals, suggesting that from its inception, the blade was destined to be more than tempered steel; it was to be a vessel for spirit and a cornerstone of samurai identity.

4.1 The Sword as a Symbol of Samurai Status and Privilege

During much of Japan's feudal era, the right to wear swords, especially the distinctive daisho pairing of the long katana and shorter wakizashi, was a privilege strictly reserved for the samurai class. This exclusivity was a powerful and visible marker of their elevated social standing and authority over other classes like farmers, artisans, and merchants. Sumptuary laws, such as those enacted during the Edo period, explicitly codified who could wear swords, reinforcing the samurai's position at the apex of the social hierarchy. The mere sight of a samurai wearing his daisho commanded respect and often fear, instantly communicating his warrior status and his legal right to use lethal force, particularly under the principle of kirisute-gomen (permission to strike down a commoner for perceived disrespect).

The quality, craftsmanship, and ornamentation of a samurai's swords also reflected his individual rank, wealth, and lineage within the buke (warrior families). A high-ranking samurai or a daimyo (feudal lord) might possess blades crafted by legendary swordsmiths, adorned with elaborate koshirae (sword mountings) featuring precious metals and intricate designs. These were not just functional weapons but also status symbols, displayed with pride and often given as prestigious gifts. The sword, therefore, was an undeniable badge of honor and a constant reminder of the samurai's unique place and responsibilities within the feudal structure. Even after the samurai class was officially dissolved during the Meiji Restoration, their descendants, the shizoku, initially retained some sword-wearing privileges, highlighting the deep-seated association between the blade and samurai identity.

4.2 The Personal Connection My Sword My Self

The bond between a samurai and his sword transcended mere ownership; it was a deeply personal and often spiritual connection, encapsulated in the saying, "The sword is the soul of the samurai" (katana wa bushi no tamashii). This belief underscored the idea that the sword was not an inanimate object but an extension of the warrior's own spirit, courage, and honor. Many samurai believed their swords possessed a living essence, sometimes referred to as tamashii, which could be influenced by both the smith who forged it and the warrior who wielded it.

Swords were treated with profound respect. They were often given names, carefully maintained, and displayed in a place of honor within the home. A samurai would never step over a sword laid on the floor, and strict etiquette governed how swords were handled, presented, and stored. These blades were frequently cherished as ancestral heirlooms, passed down through generations, carrying with them the history, honor, and spirit of the family line. The idea that a part of the owner's character was imprinted onto the blade, and vice-versa, fostered an intimate relationship. Losing one's sword, or having it confiscated, was not just a loss of a weapon but a profound blow to one's identity and honor. Celebrated swords, known as meibutsu, were often attributed with their own personalities or histories, further enhancing this mystical connection.

4.3 How the Sword Embodied Samurai Virtues and Ideals

The physical characteristics and perceived qualities of the Japanese sword were seen as direct reflections of the core virtues and ideals of Bushido, the samurai's moral code. The sword was not just a tool for enacting these virtues but a constant, tangible reminder of the principles by which a samurai was expected to live and die. The discipline required to master swordsmanship was itself a path to cultivating these virtues.

| Sword Characteristic / Quality | Embodied Samurai Virtue (Bushido Tenet) | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Uncompromising Sharpness & Cutting Ability | Gi (Rectitude/Justice), Decisiveness | The sword's ability to cut cleanly and effectively symbolized the samurai's capacity for decisive action and his commitment to upholding justice. A swift, clean cut represented a clear, unwavering moral judgment. |

| Resilience & Strength of the Steel (ability to bend without breaking, hold an edge) | Yu (Courage/Bravery), Indomitable Spirit | The blade's toughness, forged through fire and hammer, mirrored the samurai's courage in the face of adversity and his unyielding spirit, even when facing death. It represented the ability to endure hardship. |

| Purity & Clarity of the Steel (as seen in the jihada and hamon) | Meiyo (Honor), Makoto (Sincerity/Truthfulness) | The clear, often intricate patterns in the steel and the distinct temper line were seen as reflections of the samurai's pure honor and the sincerity of his intentions. A flawless blade represented an untarnished reputation. |

| Disciplined Forging Process (precision, patience, dedication of the smith) | Jisei (Self-Control), Rei (Respect/Propriety) | The immense skill, patience, and ritualistic dedication required to forge a superior sword mirrored the self-discipline and control a samurai was expected to cultivate in all aspects of his life, as well as respect for tradition and craft. |

| The Balanced & Purposeful Design | Chugi (Loyalty/Duty), Bu (Martial Prowess) | The sword was perfectly designed for its purpose, embodying the samurai's unwavering loyalty to his lord and his dedication to fulfilling his martial duties. Its balance allowed for effective and skilled use in service. |

Through these symbolic associations, the sword became a moral compass for the samurai. To care for one's sword, to train with it diligently, and to understand its deeper meaning was to cultivate the virtues essential to the warrior's identity. The concept of giri, or duty, was intrinsically linked to the sword, as it was the primary instrument through which a samurai fulfilled his obligations to his lord and society.

4.4 The Psychological Impact of Wielding the Blade

Carrying and being prepared to use the sword had a profound psychological impact on the samurai, shaping his mindset, demeanor, and perception of the world. The constant presence of the blade served as an unwavering reminder of the thin line between life and death, fostering a heightened state of awareness and readiness known as zanshin. This was not merely about combat preparedness but a state of mindful presence in all activities.

Wielding the sword imbued the samurai with a potent sense of power and responsibility. The knowledge that one possessed the means to take a life, and the societal sanction to do so under certain circumstances, could cultivate both confidence and a heavy burden. This duality demanded immense mental discipline. The rigorous training in kenjutsu (the art of swordsmanship) was not just about learning techniques; it was about forging the spirit, cultivating fudoshin (an immovable mind, calm and unperturbed in the face of danger), and striving for mushin (a mind free from distracting thoughts and emotions, able to react intuitively and spontaneously).

The psychological weight of the sword also reinforced the samurai's commitment to his code. The potential lethality of the blade necessitated a strong ethical framework to govern its use, further solidifying the importance of Bushido in the samurai's identity. The sword was a tool that demanded respect not only for its craftsmanship but for its capacity, forcing its owner to confront fundamental questions of life, death, honor, and duty on a daily basis. This constant internal dialogue, mediated by the presence of the sword, was crucial in shaping the internal landscape of the samurai warrior and his unique identity.

5. The Sword in Samurai Life Ritual and Reality

Beyond its primary function as a weapon, the Japanese sword was deeply interwoven into the fabric of samurai existence, dictating aspects of daily conduct, defining the brutal realities of combat, playing a crucial role in solemn rituals, and even featuring in artistic and ceremonial life. For the samurai, the sword was an ever-present companion, a constant reminder of their duties, status, and the precariousness of life.

5.1 Daily Wear and Etiquette of the Daisho Sword Pair

The most recognizable symbol of a samurai was the daishō (大小), literally "big-little," the pair of swords consisting of the long katana and the shorter wakizashi. The manner in which these swords were worn and handled was governed by strict rules of etiquette, reflecting the samurai's preparedness, social standing, and respect for the blade itself.

Samurai typically wore the daishō thrust through their obi (sash) on the left hip, with the cutting edge facing upwards. This allowed for a swift, fluid draw, particularly with the katana. The wakizashi, the companion sword, served as an auxiliary weapon in battle and was also used for close-quarters combat or, in dire circumstances, for ritual suicide (seppuku).

Sword etiquette, or reihō, was a critical aspect of a samurai's training and daily life:

- Entering Dwellings: When visiting another's home, a samurai would often remove their katana as a sign of peaceful intent. Depending on the host's status and the formality of the occasion, the wakizashi might also be removed or simply shifted to a less threatening position. The long sword was typically handed to a servant or placed on a designated rack (katana-kake).

- Placement of Swords: When seated, a samurai would place their sheathed katana on the floor to their right, with the hilt (tsuka) pointing away from the host, signifying no immediate intention to draw. If expecting trouble or in an untrusted environment, it might be placed on the left for quicker access.

- Respect for the Blade: A samurai's swords were considered extensions of their soul. Touching another samurai's unsheathed sword without permission was a grave offense, often leading to a duel. Even stepping over a sword lying on the floor was considered disrespectful.

- Social Settings: In formal processions or when appearing before a superior lord (daimyō), specific protocols dictated how swords were carried and presented. The quality and ornamentation of the sword mountings (koshirae)—including the tsuba (handguard), fuchi-kashira (pommel and collar), and menuki (hilt ornaments)—also conveyed the samurai's status and taste.

The daishō was not merely a set of weapons; it was a badge of honor and a constant public declaration of the samurai's identity and readiness to uphold their responsibilities.

5.2 The Sword in Combat Kenjutsu Techniques and Duels

The primary purpose of the Japanese sword was, of course, combat. Kenjutsu (剣術), the art of Japanese swordsmanship, encompassed a vast array of techniques and philosophies developed over centuries of warfare. Numerous schools, or ryūha, emerged, each with its unique approach to wielding the blade.

Key elements of kenjutsu included:

- Stances (Kamae): Various postures adopted to balance offense and defense, such as jōdan-no-kamae (high stance), chūdan-no-kamae (middle stance), and gedan-no-kamae (low stance).

- Cuts and Thrusts: Precise and powerful strikes targeting vulnerable points, often delivered with the entire body's momentum. Common cuts included shōmen-uchi (vertical head cut) and dō-giri (horizontal body cut).

- Parries and Blocks: Defensive maneuvers to deflect or stop an opponent's attack, often followed by an immediate counter-attack.

- Footwork (Ashi Sabaki): Essential for maintaining proper distance (maai) and generating power.

- Mental Fortitude: Concepts like zanshin (lingering awareness after an attack) and fudōshin (immovable mind, free from fear or distraction) were crucial for effective combat.

Duels (kettō or shinken shōbu – "true sword fight") were a stark reality for samurai, often fought to defend one's honor, settle disputes, or prove martial prowess. These were typically deadly encounters, governed by their own unwritten rules and rituals. The victor gained reputation, while the loser faced death or disgrace. Famous swordsmen like Miyamoto Musashi became legendary through their numerous duels.

Training in kenjutsu was rigorous and relentless, often beginning in early childhood. Samurai practiced with wooden swords (bokken) or bamboo swords (shinai) in dōjō (training halls) to hone their skills without the immediate lethality of a live blade, though serious injuries were still common.

5.3 Seppuku The Swords Role in Ritual Suicide and Preserving Honor

Seppuku (切腹), often known in the West by the more colloquial term hara-kiri (腹切り, "belly-cutting"), was a highly ritualized form of suicide practiced by samurai to avoid capture, atone for failure, protest injustice, or otherwise preserve their honor. The sword, typically the wakizashi or a specially designated dagger (tantō), played the central and most gruesome role in this solemn act.

The ritual of seppuku was complex and deeply symbolic:

| Element of Seppuku | Description and Significance |

|---|---|

| The Act | The samurai would kneel in a formal seated position (seiza) and, after composing themselves, plunge the short blade into their left abdomen, drawing it across to the right and then upwards. This method was chosen for its excruciating pain, demonstrating the samurai's courage and control. |

| The Kaishakunin | Often, a trusted second, known as a kaishakunin, would stand by with a katana. Their role was to perform kaishaku – a merciful decapitation – once the samurai had made the disemboweling cut, to end their suffering and prevent any display of agony that might be seen as dishonorable. The skill of the kaishakunin lay in cutting almost entirely through the neck, leaving a small flap of skin so the head would fall forward into the samurai's arms, rather than rolling away disrespectfully. |

| Setting and Attire | Seppuku was often performed in a designated, purified space, such as a garden or temple courtyard, typically on white cloth. The samurai would usually be dressed in a white kimono (shiroshōzoku), the color of death and purity. |

| Witnesses | Official witnesses were often present to ensure the ritual was carried out correctly and to attest to the samurai's bravery. |

| Death Poem (Jisei no ku) | It was customary for the samurai to compose a death poem, reflecting on life, death, or the circumstances leading to their seppuku. This poem was a final expression of their character and state of mind. |

For samurai women, a similar ritual known as jigai involved cutting the throat with a tantō or kaiken (a small dagger). Seppuku was not merely suicide; it was a profound statement of samurai values, where dying an honorable death was preferable to living in shame. The sword, in this context, transformed from a weapon of war into an instrument for the ultimate preservation of a warrior's identity and honor.

5.4 The Sword in Arts and Ceremony Beyond the Battlefield

The Japanese sword's significance extended far beyond the battlefield and the grim ritual of seppuku. It was also an object of art, a symbol in ceremonies, and a cherished heirloom.

- Gifts and Symbols of Alliance: High-quality swords were often presented as prestigious gifts between daimyō and samurai, symbolizing respect, loyalty, and the forging of alliances. The exchange of swords could seal important political or personal bonds.

- Shinto Rituals: Swords have ancient connections to Shintoism, Japan's indigenous religion. The legendary sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi is one of the Three Imperial Regalia of Japan. Swords were, and still are, used in Shinto purification rituals and as sacred offerings (gohōbi) at shrines.

- Aesthetic Appreciation (Kantei): The craftsmanship of Japanese swords led to their appreciation as art objects. Kantei, the art of sword appraisal, became a refined practice, with connoisseurs meticulously examining blades for their form, hamon (temper line), steel quality, and the smith's signature. Swords were admired for their deadly beauty and the spiritual essence believed to be imbued by the swordsmith.

- Theatrical and Festive Use: Swords featured prominently in traditional Japanese performing arts, such as Noh and Kabuki theatre, where they were used as props to signify samurai characters and dramatic conflict. They also appeared in various festivals and processions.

- Family Heirlooms: Many swords became treasured family heirlooms, passed down through generations. These blades were not just possessions but embodiments of ancestral spirit, family honor, and history.

- Tameshigiri (Test Cutting): While primarily a method to test a sword's cutting ability, tameshigiri also evolved into a martial art form, demonstrating the swordsman's skill and the blade's quality. It was sometimes performed ceremonially.

- Coming-of-Age Ceremonies: For a young samurai, receiving his first swords (often the mamorigatana, a protection sword, at a very young age, followed by the daishō later) was a significant rite of passage, marking his official entry into the samurai class and its responsibilities.

In these diverse roles, the sword transcended its utilitarian function, becoming a multifaceted symbol deeply embedded in the cultural, spiritual, and artistic life of the samurai and Japanese society as a whole. Its presence in these contexts reinforced the samurai's identity and the values they were expected to uphold, even in times of peace.

6. Shifting Tides The Sword Samurai and Identity Through Eras

The relationship between the samurai, their swords, and their identity was not static. It underwent profound transformations as Japan moved through distinct historical periods, each reshaping the warrior class and the significance of their iconic blade. From the battlefields of feudal Japan to the peaceful avenues of the Edo period and the radical societal shifts of the Meiji Restoration, the sword's role evolved, reflecting the changing tides of samurai fortune and self-perception.

6.1 The Golden Age of Samurai Dominance and Sword Culture

The "Golden Age" of samurai dominance, encompassing periods like the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1336-1573) eras, and culminating in the tumultuous Sengoku Jidai (Warring States Period, c. 1467-1603), was characterized by near-constant warfare and the ascendancy of the samurai class. During these centuries, the Japanese sword, particularly the tachi and later the katana, was primarily a brutal and effective weapon of war. Its design and craftsmanship were honed by the relentless demands of combat. Swordsmiths achieved legendary status, producing blades renowned for their sharpness, resilience, and deadly beauty.

For the samurai of this era, their identity was inextricably linked to their martial prowess and their sword. The blade was an extension of their arm and their will, a constant companion in a life defined by conflict, loyalty to their daimyo (feudal lord), and the pursuit of honor on the battlefield. The quality of a samurai's sword could mean the difference between life and death, and it also reflected his status and the power of his clan. Sword schools (ryuha) flourished, focusing on practical, life-or-death combat techniques (kenjutsu). The sword culture was raw, pragmatic, and deeply ingrained in the warrior's psyche; to be a samurai was to be a swordsman, and the sword was the ultimate arbiter in a world governed by force.

6.2 The Edo Period Peace and the Idealized Samurai Identity

The establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603 ushered in the Edo Period (1603-1868), a long era of relative peace and stability that profoundly altered the samurai's role and, consequently, their relationship with the sword. With major wars ceasing, the samurai transitioned from active combatants to a hereditary class of administrators, bureaucrats, and enforcers of social order within the rigid shinokosho four-tier class system (samurai, farmers, artisans, merchants).

6.2.1 The Sword as a Symbol More Than a Weapon of War

During the Edo Period, the sword, particularly the daisho (pair of long and short swords – katana and wakizashi), became less a tool of daily combat and more a potent symbol of samurai status, authority, and privilege. The right to wear the daisho was exclusively granted to the samurai, visibly distinguishing them from other social classes and reinforcing their elite identity. While still expected to be proficient in martial arts, the likelihood of drawing a sword in battle significantly diminished. Instead, the sword represented the samurai's readiness to uphold justice, maintain order, and defend their honor, even if its use was largely ceremonial or reserved for rare duels. There was a heightened appreciation for the aesthetic qualities of swords and their fittings (koshirae), which became elaborate works of art reflecting the owner's taste and rank.

6.2.2 The Formalization of Bushido and Martial Arts Schools

The prolonged peace of the Edo Period provided fertile ground for the philosophical and ethical codification of Bushido, "The Way of the Warrior." Thinkers like Yamaga Soko and Yamamoto Tsunetomo (author of Hagakure) articulated ideals of loyalty, self-discipline, frugal living, honor, and a preparedness for death. The samurai identity became increasingly associated with these virtues, often romanticized and idealized.

Martial arts schools (ryuha) also evolved. While practical techniques were still taught, there was a growing emphasis on kata (forms), discipline, and the spiritual and character development (seishin tanren) aspects of swordsmanship (kenjutsu) and sword drawing (iaijutsu/battojutsu). The sword became a tool for self-cultivation, a means to embody the lofty principles of Bushido. The focus shifted from merely surviving on the battlefield to perfecting oneself through the rigorous practice of the sword arts, transforming the warrior's path into a way of life (do).

6.3 The Meiji Restoration The Decline of the Samurai and Sword Prohibitions

The arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry's "Black Ships" in 1853 shattered Japan's centuries-long isolation, leading to a period of immense upheaval that culminated in the Meiji Restoration of 1868. This revolution overthrew the Tokugawa Shogunate, restored direct imperial rule under Emperor Meiji, and launched Japan on a path of rapid modernization and Westernization. For the samurai class, these changes were cataclysmic, leading to the dismantling of their traditional privileges and a fundamental crisis of identity.

6.3.1 The Haitorei Edict and its Impact on Samurai Identity

A critical blow to the samurai's traditional identity and status was the Haitorei Edict (Sword Abolition Edict) issued in 1876. This decree prohibited the public wearing of swords by most of the population, including the former samurai, effectively stripping them of their most visible and cherished symbol of distinction. For centuries, the daisho had been the samurai's exclusive right and the embodiment of their soul and social standing. The loss of this privilege was not merely symbolic; it represented the eradication of their warrior identity in the eyes of society and for many, in their own self-perception.

The impact was profound. Many former samurai struggled to adapt to a society that no longer valued their martial skills or hereditary status. Some participated in rebellions, such as the Satsuma Rebellion led by Saigo Takamori in 1877, in a desperate attempt to preserve their way of life, but these efforts were ultimately suppressed by the new imperial army. The Haitorei Edict, along with other reforms like the abolition of feudal domains and stipends, effectively dissolved the samurai class, forcing its members to find new roles in a rapidly changing Japan.

6.3.2 Preserving Sword Traditions in a Modernizing Japan

Despite the official decline of the samurai class and the prohibition on wearing swords, the legacy of the Japanese sword and its associated traditions did not vanish. Efforts began to emerge aimed at preserving swordsmithing as a unique Japanese art form and swords themselves as important cultural artifacts. Connoisseurship and collection of Nihonto (Japanese swords) continued, albeit in a different context, appreciating them for their historical significance, artistic beauty, and the incredible skill of their creators.

Martial arts centered around the sword, such as kenjutsu and iaijutsu, also underwent a transformation. They evolved into modern budo forms like Kendo ("Way of the Sword") and Iaido ("Way of Sword Drawing"). While retaining their martial roots, these disciplines increasingly emphasized character development, mental discipline, physical fitness, and the preservation of traditional techniques as a cultural heritage rather than as preparation for actual combat. Organizations like the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (Greater Japan Martial Virtue Society), established in 1895, played a role in standardizing and promoting these martial arts. Thus, even as the samurai class faded into history, the spirit of the sword and its cultural importance found new ways to endure in a modernizing Japan, shifting from a symbol of a warrior class to an emblem of national heritage and disciplined practice.

The table below summarizes the evolving role and symbolism of the Japanese sword through these critical eras, highlighting the profound shifts in its connection to samurai identity:

| Feature | Golden Age of Samurai (e.g., Kamakura, Muromachi, Sengoku) | Edo Period (Tokugawa Shogunate) | Meiji Restoration & Early Modern Japan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function of the Sword | Essential Weapon of War and Survival; tool for conquest and defense. | Symbol of Status, Authority, and Social Order; rarely used in combat. | Art Object, Cultural Heritage, Tool for Budo; practical combat use obsolete. |

| Sword's Connection to Samurai Identity | Integral to the identity as a warrior and combatant; an extension of self. | Definitive marker of elite samurai class and moral exemplar; badge of privilege. | A lost symbol of a defunct class; later, a link to historical legacy and tradition. |

| Bushido (Way of the Warrior) | A practical, uncodified martial code focused on battlefield conduct and loyalty. | A formalized philosophical and ethical system; idealized virtues. | An idealized legacy influencing national spirit and martial arts philosophy. |

| Public Sword Carrying | Constant and necessary for combat readiness and personal defense. | The daisho (katana and wakizashi) as an exclusive right and duty of samurai. | Prohibited by the Haitorei Edict (1876) for most of the population. |

| Swordsmithing Focus | Driven by battlefield performance, sharpness, and durability. | Increased emphasis on artistic beauty, elaborate fittings (koshirae), and tradition. | Efforts focused on preservation of traditional techniques and art appreciation. |

7. Enduring Legacy The Japanese Sword and Samurai Identity Today

The echoes of the samurai and the gleam of their iconic swords resonate far beyond the battlefields of feudal Japan. Even in the 21st century, the Japanese sword, particularly the katana, remains a potent symbol, deeply interwoven with both contemporary Japanese identity and a global fascination with the samurai ethos. This enduring legacy manifests in diverse forms, from revered cultural artifacts and living martial traditions to influential popular culture and the dedicated pursuit of collectors.

7.1 The Sword in Modern Japanese Culture and National Identity

In modern Japan, the sword, or Nihonto, transcends its historical function as a weapon. It is revered as a pinnacle of traditional craftsmanship (monozukuri) and an embodiment of the Japanese spirit (Yamato-damashii). Many ancient and significant blades are designated as National Treasures (Kokuhō) or Important Cultural Properties (Jūyō Bunkazai), meticulously preserved and displayed in institutions like the Tokyo National Museum and the Japanese Sword Museum (Token Hakubutsukan) in Tokyo. These swords are not merely historical objects; they are seen as carriers of cultural DNA, representing discipline, artistic excellence, and a profound connection to the nation's past.

While Japan has embraced pacifism, the sword continues to symbolize purity, resilience, and the pursuit of perfection. For some families, an ancestral sword is a cherished heirloom, a tangible link to their lineage and the virtues associated with the samurai. The meticulous process of swordsmithing itself, using traditional methods to forge tamahagane steel, is a respected art form, highlighting a dedication to quality and tradition that is highly valued in Japanese society. The sword, therefore, contributes to a nuanced national identity, one that respects its martial heritage while championing peace and artistic refinement.

7.2 Samurai Ideals and Swords in Global Popular Culture

The allure of the samurai, their code of Bushido, and their iconic swords has captivated audiences worldwide, profoundly influencing various forms of popular media. This global reach has cemented the samurai and the katana as instantly recognizable symbols, though often romanticized or stylized.

7.2.1 Influence in Cinema Literature Anime and Video Games

The portrayal of samurai and their swords in popular culture has been a significant factor in shaping global perceptions of this warrior class and their connection to their blades.

- Cinema: Japanese filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa, with masterpieces such as Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, introduced the world to compelling samurai narratives. Hollywood has also explored samurai themes, notably in films like The Last Samurai, which, while fictionalized, brought samurai ideals to a vast international audience. Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill series heavily features katana and pays homage to samurai film tropes. These cinematic representations often emphasize the sword as an extension of the warrior's skill and spirit.

- Literature: Historical novels, such as James Clavell's Shōgun, have provided immersive (though sometimes Westernized) perspectives on feudal Japan and the samurai. Manga series like Takehiko Inoue's Vagabond (based on the life of Miyamoto Musashi) and Hiroaki Samura's Blade of the Immortal offer intricate storytelling and vivid depictions of sword combat, exploring the philosophical and personal dimensions of a swordsman's life.

- Anime: Anime has been a powerful medium for popularizing samurai imagery. Series like Rurouni Kenshin, which follows a former assassin wielding a reverse-blade sword (sakabatō) in the Meiji era, explore themes of atonement and the changing role of the samurai. Samurai Champloo offers a stylized, hip-hop-infused take on samurai adventures, while series like Gintama blend samurai settings with comedy and science fiction. These shows often highlight the sword's symbolic weight and the moral complexities faced by its wielder.

- Video Games: The interactive nature of video games allows players to step into the role of a samurai. Titles like Ghost of Tsushima, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, and the Nioh series offer immersive experiences centered around sword combat and samurai lore. Fighting game franchises such as Soulcalibur and Samurai Shodown feature numerous characters wielding various Japanese swords, further embedding these weapons into global gaming culture. These games often emphasize the mastery of the blade as a core element of samurai identity and power.

Through these diverse media, samurai ideals such as honor, loyalty, self-discipline, and martial prowess, along with the iconic image of the katana, continue to inspire and entertain, contributing to a persistent global fascination.

7.3 The Practice of Iaido and Kendo Keeping the Spirit of the Sword Alive

The spirit of the samurai and their dedication to swordsmanship are preserved and cultivated through traditional Japanese martial arts known as budō. Among these, Iaido and Kendo are particularly significant for their direct connection to the Japanese sword, offering practitioners living traditions that preserve warrior disciplines and philosophies.

Iaido (居合道) is the art of drawing the sword, cutting, and re-sheathing it in a single, fluid motion. It primarily involves the practice of kata (pre-arranged forms) against one or more imaginary opponents. The focus is on mental concentration, precision, calmness, and the seamless unity of mind, body, and sword. Practitioners often use an iaitō (an unsharpened training sword) or, for advanced students, a shinken (a sharp, real sword). Iaido emphasizes zanshin (lingering awareness) and the spiritual development of the individual.

Kendo (剣道), or "the Way of the Sword," is a dynamic martial art where practitioners wear protective armor (bōgu) and use bamboo swords (shinai) to strike specific targets on their opponents. Kendo matches are characterized by powerful strikes accompanied by strong shouts (kiai). Beyond the physical combat, Kendo aims to cultivate character, emphasizing respect, etiquette (reigi), and the relentless pursuit of self-improvement. It seeks to apply the principles of the katana to life.

The table below highlights key distinctions between these two prominent sword arts:

| Feature | Iaido | Kendo |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Art of drawing, cutting, and sheathing (kata-based) | Sparring and striking with bamboo swords against a live opponent |

| Equipment | Iaitō (unsharpened practice sword) or Shinken (real sword) | Shinai (bamboo sword), Bōgu (protective armor) |

| Opponent | Primarily conceptual or imaginary (within kata) | Live, armored opponent |

| Core Philosophy | Mental discipline, precision, spiritual refinement, awareness (zanshin) | Cultivating spirit (kiai), etiquette (reigi), full-contact engagement, character development |

Through dedicated practice of Iaido, Kendo, and other related arts like Kenjutsu (classical sword combat techniques), individuals today can connect with the samurai legacy, not just by learning fighting techniques, but by embodying the discipline, focus, and respect that were central to the warrior's way of life. These arts ensure that the spirit of the sword continues to shape and inspire.

7.4 Collecting and Appreciating Japanese Swords as Art and History

The Japanese sword is highly esteemed worldwide not only as a historical weapon but also as a sophisticated art form. A global community of collectors, scholars, and enthusiasts dedicates itself to the study, preservation, and appreciation of Nihonto. These swords are considered tangible links to Japan's feudal past and marvels of metallurgical and artistic achievement.

Organizations such as the Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai (NBTHK, The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords) play a crucial role in authenticating, evaluating, and promoting Japanese swords. Sword appraisal, or kantei, is a refined skill, requiring deep knowledge of different periods, schools, and individual smiths.

Collectors and connoisseurs value swords based on several factors:

- Historical Period: Swords are broadly categorized into Kotō (old swords, pre-1596), Shintō (new swords, 1596-1780), Shinshintō (new new swords, 1781-1876), Gendaitō (modern swords, 1876-1945), and Shinsakutō (newly made swords, post-1953).

- Craftsmanship: The quality of the forging, the beauty of the hamon (temper line), the texture of the steel (jihada), and the overall shape and balance are paramount.

- Swordsmith: Blades made by legendary smiths like Masamune or Muramasa, or other highly-rated masters, are exceptionally prized.

- Condition and Provenance: The state of preservation, any historical records, and previous ownership can significantly impact a sword's value.

- Artistic Mountings (Koshirae): The scabbard (saya), hilt (tsuka), and fittings (kodōgu) are often exquisite works of art in their own right, reflecting the aesthetic tastes of different eras.

Collecting Japanese swords is more than an investment; it is an engagement with history, art, and a unique cultural heritage. Each blade tells a story, embodying the skill of its creator and the spirit of the age in which it was forged. Exhibitions and private collections allow these masterpieces to be admired, ensuring that the legacy of Japanese swordsmithing continues to be cherished and understood by future generations.

8. Summary

The Japanese sword, far more than a mere instrument of war, stands as a profound and enduring symbol inextricably linked to the identity of the samurai and, by extension, to significant aspects of Japanese culture. From its origins as a formidable battlefield weapon to its elevation as the "soul of the samurai," the sword has embodied the warrior's virtues, status, and spiritual aspirations. The meticulous art of its creation, the rigorous discipline of its use, and the deep philosophical underpinnings associated with it—all contributed to forging a unique warrior identity centered on honor, loyalty, and martial excellence.

Throughout Japanese history, the sword's role evolved: from the practical weapon of the early samurai, to the status symbol and artistic object of the peaceful Edo period, and even surviving the Meiji Restoration's prohibitions to re-emerge as a cherished cultural icon. Its sacred and spiritual significance, influenced by Shinto and Zen Buddhist beliefs, imbued the blade with a mystique that transcended its physical form, making it a mirror of the warrior's inner self.

Today, the legacy of the Japanese sword and the samurai identity continues to thrive. It is preserved in the revered craftsmanship of Nihonto, celebrated in museums and private collections, and kept alive through the dedicated practice of martial arts like Kendo and Iaido. Globally, the samurai and their swords have become powerful archetypes in popular culture, influencing cinema, literature, anime, and video games, and shaping worldwide perceptions of Japanese warrior traditions. The Japanese sword, therefore, remains a potent emblem—a testament to a unique historical and cultural phenomenon, reflecting not only the soul of the samurai but also an enduring human fascination with the interplay of art, power, and identity.

9. Summary

This exploration has illuminated the profound and multifaceted relationship between the Japanese sword, the samurai warrior, and the very fabric of their identity. Far more than a mere instrument of combat, the Nihonto, or Japanese sword, served as the embodiment of the samurai's soul (tama), a sacred emblem of their elite status within feudal Japanese society, and an unwavering companion that shaped their philosophy, daily life, and ultimate destiny. The journey through the history and culture surrounding these iconic blades reveals how deeply intertwined the warrior and their weapon became, forging an identity recognized worldwide.

We have seen how the meticulous and spiritual art of Japanese swordsmithing, from the ritualistic creation of Tamahagane steel to the legendary skills of master smiths like Masamune and Muramasa, produced blades of unparalleled quality and beauty. The archetypal Katana, often paired with the Wakizashi to form the Daisho, stood as the primary symbol of the samurai. However, other blades like the earlier Tachi, designed for cavalry, and the Tanto, a dagger for close-quarters and ritual, each played significant roles. Beyond their practical applications, these swords were imbued with a deep sacred and spiritual significance, often considered to house kami or divine spirits, reflecting Shinto beliefs and the samurai's reverence for their weapons.

The ascendancy of the samurai class was inextricably linked to the development and codification of Bushido, the Way of the Warrior. This complex ethical and moral code, profoundly influenced by Zen Buddhism's emphasis on discipline and mindfulness, and Shinto's reverence for ancestry and nature, guided the samurai's conduct. Core tenets such as Gi (Justice), Yu (Courage), Jin (Benevolence), Rei (Respect), Makoto (Honesty), Meiyo (Honor), and Chugi (Loyalty) were not abstract ideals but principles to be lived and, if necessary, died for, with the sword often being the ultimate arbiter of these virtues, particularly in the preservation of honor through Seppuku.

The sword was the most potent symbol of the samurai's station, a clear demarcation of their privileges and responsibilities within the Buke (warrior families) and broader society. The personal connection, often described as "my sword, my self," underscored the idea that the blade was an extension of the warrior's being. It was through the mastery and respectful handling of the sword, in arts like Kenjutsu, that samurai honed not only their martial skills but also their character, embodying the virtues espoused by Bushido. The psychological impact of carrying and potentially wielding such a blade fostered a unique warrior consciousness, centered on readiness, discipline, and an acute awareness of life and death.

The following table encapsulates the critical dimensions of the Japanese sword's role in shaping and reflecting samurai identity:

| Core Theme | Elaboration on the Sword-Samurai-Identity Nexus |

|---|---|

| The Sword as a Material & Spiritual Icon | Represents the pinnacle of Japanese craftsmanship (Tamahagane, legendary smiths). The variety of blades, including the Katana, Wakizashi, Tanto, and Tachi, each served specific functions while collectively symbolizing martial readiness. Perceived as more than mere metal, these swords were often considered sacred objects, sometimes believed to house a spirit or soul. |

| Bushido: The Warrior's Code Forged with Steel | The sword was central to the samurai's ethical framework. Bushido's virtues – honor, loyalty, courage, discipline, and rectitude – were intrinsically linked to the sword, which served as both a tool for upholding these principles and a symbol of the samurai's commitment to them. |

| Identity Embodied: The Sword as Self | Served as an undeniable marker of samurai status and privilege. The profound personal connection ("My Sword, My Self") highlighted the blade as an extension of the warrior's own being. It was the ultimate instrument for defending personal and familial honor, most starkly demonstrated in the ritual of Seppuku. |

| Evolution Across Eras: From Battlefield to Symbol | The sword's role transformed over centuries. In early feudal Japan, it was a primary weapon of war. During the prolonged peace of the Edo period, while still a weapon, it increasingly became a potent symbol of authority, social standing, and martial philosophy. Even after the samurai class was officially dissolved during the Meiji Restoration and the Haitorei Edict prohibited sword-wearing, its cultural and spiritual significance endured. |

| Enduring Resonance: Legacy in Modern Times | The Japanese sword and samurai ideals continue to hold a powerful allure. They are integral to Japan's national identity, have profoundly influenced global popular culture (cinema, anime, literature, video games), and inspire modern martial arts like Kendo and Iaido. Antique swords are treasured as invaluable works of art and historical artifacts. |

Throughout Japan's dynamic history, the perception and role of both the samurai and their swords underwent significant transformations. From the turbulent "Golden Age" of samurai dominance in warfare, where martial prowess and the quality of one's blade were paramount, to the relative tranquility of the Edo period. During this latter era, the samurai identity became more idealized, and the sword, while still worn as part of the Daisho, transitioned into a more potent symbol of status and refined martial philosophy than an everyday tool of conflict. Bushido and various Ryu (martial arts schools) became more formalized. The Meiji Restoration heralded the end of the samurai class and introduced prohibitions like the Haitorei Edict, fundamentally altering the samurai's societal role and relationship with their swords. Yet, even in the face of such upheaval, concerted efforts were made to preserve the rich traditions of swordsmanship and swordsmithing, recognizing their cultural value.

In conclusion, the Japanese sword is far more than a relic of a bygone martial age. It remains a powerful testament to the samurai's enduring spirit, their intricate code of ethics, and the unique identity they forged. Its legacy persists robustly in modern Japanese culture, influencing national identity and inspiring a global fascination with samurai ideals through various media. The dedicated practice of martial arts such as Iaido (the art of drawing the sword) and Kendo (the way of the sword) keeps the discipline and spirit associated with the blade alive. Furthermore, the meticulous collection and scholarly appreciation of antique Japanese swords as unparalleled works of art and significant historical artifacts ensure that the profound connection between the sword, the samurai, and their indelible identity continues to be understood and revered by generations to come.

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Related Articles

Leave a comment: