Discover why Japanese swords are renowned for their cutting excellence. Unique Tamahagane, differential hardening, precise blade geometry, and master craftsmanship combine to achieve unparalleled cutting performance.

1. The Foundation Tamahagane Steel

At the heart of the Japanese sword's legendary cutting prowess lies its unique foundational material: Tamahagane steel. Unlike modern steels, Tamahagane is a traditionally smelted steel, painstakingly produced in a specialized clay furnace known as a tatara. This ancient process, which dates back over a thousand years, is not merely a method of steel production but the initial step in crafting a blade capable of both incredible sharpness and surprising resilience.

The creation of Tamahagane is a labor-intensive, multi-day process involving iron sand (satetsu) and charcoal. The resulting steel bloom, called a kera, is far from uniform. It contains varying carbon concentrations and impurities, which are precisely what master swordsmiths utilize in the subsequent forging stages to achieve the sword's ultimate performance characteristics.

1.1 The Unique Composition of Tamahagane

The raw Tamahagane kera is not a homogenous block of steel. Instead, it comprises a mosaic of different carbon contents, ranging from very low carbon (similar to wrought iron) to high carbon steel. This inherent variability is not a flaw but a crucial feature that allows the swordsmith to select and combine pieces to achieve specific properties within the finished blade.

During the breaking down of the kera, the swordsmith meticulously sorts the steel pieces based on their carbon content and purity, identified by their appearance and fracture patterns. Generally, the steel is categorized into:

| Tamahagane Type | Carbon Content | Characteristic | Primary Use in Sword |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Carbon | Approx. 1.0 - 1.5% | Extremely hard, holds a sharp edge, but brittle. | Outer skin (kawagane) and cutting edge (hagane). |

| Low Carbon | Approx. 0.3 - 0.6% | Softer, more flexible, and resilient. | Core (shingane) and spine (mune). |

| Medium Carbon | Approx. 0.6 - 1.0% | Balanced properties, often used for outer layers. | Intermediate layers. |

This careful selection is fundamental, as it dictates the initial properties that will be further refined through the subsequent forging and folding processes. The goal is to create a blade that is both incredibly sharp and remarkably tough, a duality that is exceptionally difficult to achieve with a single, uniform type of steel.

1.2 The Folding and Forging Process

Once the Tamahagane pieces are sorted, they undergo a rigorous process of heating, hammering, and folding. This multi-stage forging is not merely about shaping the steel; it is a sophisticated method of refining its internal structure, removing impurities, and creating the layered composition that is synonymous with Japanese swords.

1.2.1 Removing Impurities and Homogenizing Carbon

The initial stages of folding are primarily focused on purification and homogenization. The selected pieces of Tamahagane are stacked, heated to high temperatures, and then hammered flat. This process is repeated multiple times, with the steel block being folded over on itself after each flattening. Each fold effectively doubles the number of layers, and with each hammering, non-metallic impurities, known as slag, are expelled from the steel. This expulsion is visible as sparks during the hammering process.

Simultaneously, the repeated heating and hammering work to homogenize the carbon content within the steel. Even though different carbon steels were initially selected, the intense forging helps to distribute the carbon more evenly throughout the selected block, ensuring a consistent base material for the specific parts of the sword (e.g., the outer skin or the core). This meticulous refinement ensures that the steel is as clean and consistent as possible before the blade's final form begins to emerge.

1.2.2 Creating Layers for Strength and Flexibility

After the initial purification and homogenization, the folding process continues, but with a refined purpose: to create the thousands of microscopic layers that give the Japanese sword its legendary combination of hardness and flexibility. Typically, the steel block is folded between 10 to 15 times, resulting in an astonishing number of layers—often exceeding 30,000. Each fold creates a distinct boundary within the steel, leading to a complex internal grain structure often visible as a subtle pattern on the finished blade.

This layering achieves several critical objectives for cutting performance:

- Differential Hardness: By combining different carbon steels (e.g., a harder outer skin, kawagane, with a softer core, shingane), the layering ensures the blade possesses a hard, sharp edge while maintaining a resilient, shock-absorbing body.

- Impact Absorption: The numerous layers act as internal shock absorbers, distributing the stress of an impact across the blade and preventing catastrophic failure, such as snapping.

- Edge Retention and Toughness: The combination of hard and soft layers contributes to superior edge retention. While the hard layers provide keenness, the underlying softer layers prevent the edge from chipping easily. This microscopic flexibility within the edge itself allows it to withstand significant stress during a cut.

The mastery of the folding process transforms raw Tamahagane into a composite material perfectly engineered for the dynamic forces encountered during cutting, laying the essential groundwork for the subsequent stages of sword crafting.

2. The Art of Differential Hardening

2.1 The Clay Tempering Process Yakiba

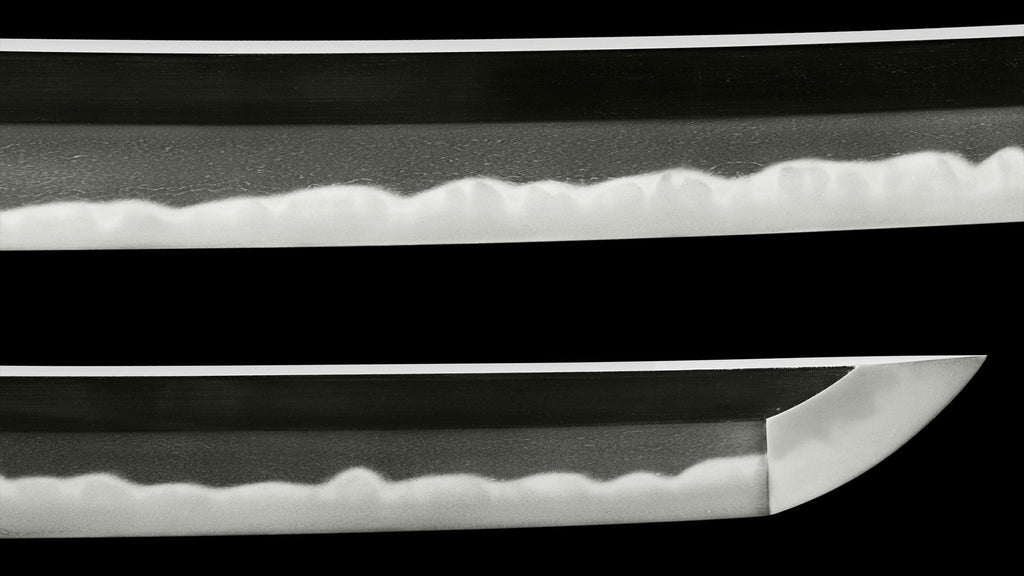

2.2 The Visible Hamon Line

2.3 Balancing a Hard Edge with a Resilient Spine

| Feature | Cutting Edge (Ha) | Spine (Mune) & Body (Ji) |

|---|---|---|

| Microstructure | Martensite | Pearlite / Bainite (Softer Steel) |

| Hardness (Approx. Rockwell) | Extremely Hard (60-65 HRC) | Softer (40-50 HRC) |

| Primary Function | Achieves and retains a razor-sharp edge for superior cutting performance. | Absorbs shock, prevents breakage, provides flexibility and resilience (*shinae*). |

| Benefit for Cutting | Allows for precise, clean cuts through various materials. | Prevents the blade from snapping upon impact, allowing it to bend and spring back. |

3. Masterful Blade Geometry and Design

Beyond the exceptional steel and the sophisticated heat treatment, the geometric design of a Japanese sword is meticulously crafted to optimize its cutting performance. Every curve, angle, and surface plays a critical role in how the blade interacts with a target, ensuring efficiency, durability, and devastating effectiveness.

3.1 The Curvature Sori for Draw Cuts

One of the most distinctive features of a Japanese sword is its elegant curvature, known as Sori. This curve is not merely aesthetic; it is a fundamental aspect of the blade's cutting mechanics. Unlike a straight blade that primarily chops or impacts, the Sori allows for a unique cutting technique called hiki-giri, or "draw cut."

When a curved blade is drawn across a target, the Sori enables a slicing motion that maximizes the effective length of the edge in contact with the material. This action distributes the force along a greater surface area of the edge, reducing resistance and allowing the blade to pass through with remarkable ease. It's akin to using a saw rather than an axe, facilitating a clean, efficient cut rather than a brute-force impact. This inherent design allows for superior penetration and minimal binding within the target, a crucial advantage in combat and cutting tests.

3.2 The Cross Section Shinogi and Niku

The cross-sectional geometry of a Japanese sword is a complex interplay of various elements, primarily the Shinogi (ridge line) and Niku (meat or convexity). These features are critical for balancing the blade's sharpness with its strength and ability to cleave through material without getting stuck.

The most common and effective cross-section for cutting is the Shinogi-zukuri. In this design, a distinct ridge line (Shinogi) runs along the length of the blade, creating a triangular profile that tapers towards the edge (Ha) and the spine (Mune). The area between the Shinogi and the Ha is called the Ji, and the area between the Shinogi and the Mune is the Shinogi-ji.

Niku refers to the amount of convexity or "fullness" behind the edge. A blade with ample Niku (known as "hamaguri-ba" or clam-shaped edge) is thicker behind the cutting edge, providing significant support and durability, making it resistant to chipping or bending during a cut. While too much Niku can reduce keenness, too little makes the edge fragile. The master swordsmith skillfully balances this convexity to ensure the blade can sustain repeated powerful impacts while still achieving a razor-sharp cut. The Shinogi itself acts as a wedge, helping to part the material after the initial edge penetration, preventing the blade from binding within the target.

| Geometric Feature | Description | Contribution to Cutting Excellence |

|---|---|---|

| Shinogi (Ridge Line) | The prominent ridge running lengthwise along the blade, typically defining the transition from the flat blade surface (Ji) to the spine side (Shinogi-ji). | Acts as a wedge to part the material after the initial edge penetration, preventing the blade from binding and reducing friction. Aids in clean, efficient cuts. |

| Niku (Convexity/Meat) | The subtle convex curvature or fullness of the blade surface behind the cutting edge (Ha). | Provides structural support and durability to the edge, making it resistant to chipping, rolling, or bending upon impact. Essential for maintaining edge integrity during powerful cuts. |

| Shinogi-zukuri (Cross-Section) | The most common blade cross-section, characterized by a distinct Shinogi (ridge line) that creates a triangular profile. | Optimizes the blade's ability to slice and cleave through targets with minimal resistance, combining the benefits of a sharp edge with robust structural integrity. |

3.3 The Point Kissaki and Edge Angle Ha

The tip of the Japanese sword, known as the Kissaki, is not merely a pointed end but a complex, multi-faceted geometry crucial for both piercing and initiating cuts. Its precise angles and transitions dictate how effectively the blade can penetrate a target before the main cutting edge engages. The length and shape of the Kissaki (e.g., Ko-kissaki, Chu-kissaki, O-kissaki) are carefully considered by the swordsmith to complement the overall blade design and intended use.

Finally, the Ha, or the cutting edge itself, is the culmination of all these design elements. While the Tamahagane steel and differential hardening provide the inherent properties, the ultimate sharpness and cutting ability depend heavily on the precise angle and refinement of the Ha. Japanese swords typically feature a convex edge profile (hamaguri-ba), which offers a superior balance of sharpness and durability compared to a simple V-shaped edge. This subtle curvature allows the edge to be incredibly keen while still having enough material behind it to withstand the stresses of cutting. The meticulous work of the master polisher is essential in revealing and refining this perfect edge angle, ensuring that the blade can slice through even resistant materials with astonishing ease and maintain its keenness.

4. The Role of the Master Swordsmith Katanakaji

While the quality of materials and the scientific principles of metallurgy are crucial, the ultimate realization of a Japanese sword's unparalleled cutting ability rests squarely on the shoulders of the master swordsmith, or Katanakaji. Their role transcends mere craftsmanship; it is an intricate blend of artistry, scientific understanding, and spiritual dedication honed over centuries.

4.1 Generations of Accumulated Knowledge

The journey to becoming a Katanakaji is not a short one; it is a lifelong pursuit deeply rooted in tradition and lineage. Unlike modern manufacturing, the art of Japanese sword making has been preserved and perfected through generations of master-apprentice relationships.

- Lineage and Apprenticeship: Knowledge is passed down directly from master to disciple, often within families or established schools. This ensures that the subtle nuances, secret techniques (hi-den), and practical wisdom accumulated over centuries are not lost but rather refined and passed on.

- Years of Dedication: An aspiring swordsmith typically spends many years, sometimes decades, as an apprentice, starting with mundane tasks and gradually learning every facet of the process under the watchful eye of their master. This intense, hands-on training instills a deep understanding of the materials and processes, from the initial smelting of iron sand to the final shaping of the blade.

- Spiritual and Ritualistic Aspects: For many Katanakaji, sword making is not just a profession but a spiritual endeavor. Rituals, prayers, and purification rites are often performed throughout the forging process, reflecting the profound respect for the blade and its purpose. This spiritual dedication is believed to imbue the sword with a unique essence and focus the swordsmith's mind on perfection.

- Adapting and Innovating: While tradition is paramount, master swordsmiths also subtly adapt and innovate within established frameworks. They constantly strive to improve the blade's performance, resilience, and beauty, ensuring the craft continues to evolve while honoring its heritage.

4.2 Precision in Every Step of Creation

From the initial selection of tamahagane to the final shaping of the blade, the swordsmith's hands-on precision and intuitive judgment are indispensable. Every single strike of the hammer, every adjustment in temperature, and every decision on shaping directly impacts the final blade's performance as a cutting tool.

| Stage of Creation | Swordsmith's Precision Role | Impact on Cutting Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Tamahagane Selection & Preparation | Carefully assessing the quality and composition of raw steel blocks, selecting optimal pieces for different parts of the blade based on their carbon content and purity. | Ensures the foundational material has the necessary purity and carbon distribution for a strong, sharp, and resilient edge. |

| Folding and Forging (Orikaeshi Tanren) | Controlling heat, timing, and hammer force during repeated folding to homogenize carbon, remove impurities, and create precise layers within the steel. | Develops the steel's internal structure, enhancing toughness, flexibility, and the ability to hold a razor-sharp edge without breaking under stress. |

| Differential Hardening (Yakiba-ire) | Applying the clay mixture (yakiba) with exact thickness and pattern along the blade, then precisely controlling the quenching temperature and timing in water. | Creates the incredibly hard edge (ha) for superior sharpness and edge retention, while maintaining a resilient, shock-absorbing spine (mune) that prevents brittle fractures. |

| Blade Shaping and Grinding (Sunobe & Hira-zukuri) | Meticulously shaping the blade's overall geometry (sugata), including its curvature (sori), cross-section (shinogi-zukuri), and tip (kissaki), often before the final polishing. | Determines the blade's balance, cutting efficiency through various targets (e.g., for draw cuts), and overall structural integrity. A precise geometry facilitates clean, effective cuts. |

| Final Adjustments and Refinement | Making minute adjustments to the blade's profile, ensuring perfect balance, alignment, and the integrity of the edge before handing it over for expert polishing. | Ensures the blade is perfectly poised for optimal cutting dynamics and provides the best possible foundation for the polisher to reveal its full potential. |

The swordsmith's profound understanding of steel, heat, and form allows them to manipulate the material with unparalleled skill, transforming raw iron sand into a functional work of art. It is this unwavering commitment to perfection at every stage that elevates the Japanese sword beyond a mere weapon to a testament of human ingenuity and dedication to the craft.

5. The Importance of Expert Polishing Togishi

While the swordsmith forges the soul of the blade, it is the expert polisher, known as a Togishi, who brings it to life. This highly specialized artisan is responsible for transforming a rough, unrefined steel bar into a gleaming, functional, and aesthetically stunning work of art. The Togishi's work is not merely about making the sword shiny; it is a critical process that unlocks the blade's inherent cutting capabilities and reveals the intricate beauty hidden within the steel.

5.1 Revealing the Blade's True Potential

The polishing process is a painstaking, multi-stage endeavor, often taking weeks or even months for a single blade. It involves a sequence of progressively finer natural and artificial polishing stones, each designed to refine the surface and remove scratches left by the previous stage. The Togishi meticulously works the blade, using water and various grades of stones, from coarse to extremely fine. This labor-intensive process serves several crucial purposes:

- Surface Refinement: The initial stages remove forging marks and prepare the surface for finer work.

- Blade Geometry Adjustment: The polisher subtly adjusts the blade's contours, ensuring the optimal geometry for cutting, including the sori (curvature), shinogi (ridge line), and niku (blade convexity).

- Revelation of Internal Structure: As the polishing progresses, the Togishi skillfully reveals the hada (grain patterns) within the steel, a testament to the folding and forging process. These patterns, such as Itame (wood grain) or Masame (straight grain), are unique to each blade.

- Hamon Definition: The differential hardening process creates the distinct hamon (temper line). The polisher carefully etches and highlights this line, bringing out its intricate details and variations, making it a prominent feature.

- Aesthetic Enhancement: The final stages of polishing, often using specialized techniques like hazuya and jizuya stones, bring out the luster of the steel and the subtle reflections (utsuri) in the ji (blade body), elevating the sword to a true art piece.

The Togishi's skill lies in their ability to read the steel and understand the swordsmith's intentions, knowing precisely how to manipulate the stones to bring out the best in each unique blade without removing too much material or altering its fundamental structure.

5.2 Enhancing Cutting Performance and Aesthetics

Beyond its artistic significance, the polishing process is directly linked to the sword's cutting performance. A perfectly polished blade is not just beautiful; it is also incredibly functional. The Togishi's final touch on the ha (edge) and kissaki (point) is what creates the razor-sharpness for which Japanese swords are renowned.

The precision of the edge angle, combined with the smooth, low-friction surface created by polishing, allows the blade to slice through targets with minimal resistance. An improperly polished blade, even if forged perfectly, would struggle to perform effectively in cutting tests (Tameshigiri) or real-world applications. The Togishi ensures that the edge is not only sharp but also durable, capable of maintaining its keenness.

The synergy between the swordsmith's forging and the polisher's finishing work is what truly defines a Japanese sword's excellence. The Togishi transforms the raw potential of the steel into a fully realized instrument of cutting precision and an object of profound beauty. This final stage is crucial for both the sword's practical application and its appreciation as a cultural masterpiece.

Here's a comparison illustrating the impact of professional polishing:

| Aspect | Unpolished Blade (Aragane) | Professionally Polished Blade (Togishi-shiage) |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Rough, dark, covered in forging scale and marks. Internal patterns are hidden. | Gleaming, reflective surface revealing intricate hada and a distinct hamon. |

| Sharpness | Dull, unrefined edge; not suitable for cutting. | Razor-sharp, precisely angled edge optimized for clean cuts. |

| Cutting Performance | Poor, high friction, prone to binding or damaging material. | Exceptional, smooth passage through targets due to refined geometry and edge. |

| Aesthetic Value | Raw material, no artistic appeal. | Highly valued as a functional art piece, showcasing the smith's skill. |

| Durability of Edge | Uncertain, potentially brittle or prone to rolling. | Optimized for both sharpness and resilience, ensuring edge retention. |

6. The Practice of Tameshigiri Cutting Tests

6.1 Proving the Blade's Effectiveness

While the meticulous craftsmanship of a Japanese sword is evident in its creation, its ultimate purpose lies in its cutting ability. Tameshigiri (試し斬り), or "test cutting," is the traditional and modern practice of evaluating a sword's sharpness, structural integrity, and the swordsmith's skill by cutting specific targets. Historically, this practice was crucial for verifying a newly forged blade's quality before it was entrusted to a samurai.

The targets used in Tameshigiri have varied over time, reflecting the practical needs of different eras. Traditionally, common materials included bundles of straw (often soaked to simulate flesh and bone density), bamboo, and even cadavers or condemned criminals (known as tsujigiri, though this practice was rare and highly regulated, primarily for testing rather than wanton violence). Today, the most common and ethically accepted target is the tatami omote (畳表), the woven rush matting used for the surface of tatami floors, which is rolled tightly and soaked in water to provide a consistent resistance similar to human tissue.

The effectiveness of a sword in Tameshigiri is not merely about brute force; it's about the blade's geometry, the edge's sharpness, and the wielder's technique. A well-made Japanese sword, when wielded correctly, should cut through targets with minimal resistance, leaving a clean, precise cut. This demonstrates the superior qualities of the blade, from its differential hardening (Hamon) to its optimal blade geometry (Sori, Shinogi, Niku, Kissaki).

6.1.1 Common Tameshigiri Targets and Their Characteristics

| Target Material | Characteristics | What it Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Tatami Omote (Soaked) | Rolled, soaked straw mats; provides resistance similar to soft tissue. | Edge sharpness, blade geometry, wielder's edge alignment (Hasuji). |

| Bamboo | Hard, fibrous material; varies in thickness. | Blade integrity, ability to withstand impact, resistance to chipping or bending, wielder's power and precision. |

| Makiwara (Dry Straw) | Bundles of dry straw; less resistance than soaked tatami. | Basic cutting mechanics, speed, and precision. |

6.2 The Connection Between Sword and Wielder

Beyond evaluating the blade itself, Tameshigiri serves as a critical practice for the martial artist. It is a direct test of the wielder's skill, precision, and understanding of the sword's dynamics. The act of cutting demands perfect alignment of the blade (Hasuji), proper body mechanics, and a deep understanding of the sword's balance and weight distribution. A successful cut is a testament to the harmony between the sword and its user.

For practitioners of traditional Japanese martial arts like Iaido or Kenjutsu, Tameshigiri provides invaluable feedback. It allows them to refine their techniques, understand the subtle nuances of different cuts (e.g., Kesa-giri, Do-giri), and develop the mental focus necessary for effective swordsmanship. The tactile feedback of a clean cut, or the resistance of a poorly executed one, reinforces lessons learned through countless hours of practice.

Ultimately, Tameshigiri bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. It underscores the fact that even the most perfectly crafted Japanese sword requires a skilled hand to unleash its full cutting potential. This practice reinforces the profound connection between the inanimate blade and the living spirit of the wielder, making the sword an extension of their will and mastery.

7. Historical Context and Battlefield Effectiveness

The unparalleled cutting ability of Japanese swords is not merely a theoretical marvel; it was rigorously proven and refined over centuries on the battlefields of Japan. Understanding their historical context reveals how these blades evolved to meet the brutal demands of combat, becoming an extension of the warrior's will and skill.

7.1 Evolution of the Japanese Sword

The journey of the Japanese sword from its earliest forms to the iconic katana is a testament to continuous innovation driven by battlefield necessity. Early Japanese swords, such as the straight, single-edged chokuto from the Kofun period, were primarily designed for thrusting and simple slashing. However, as mounted combat became prevalent and armor evolved, a new design was needed to maximize cutting efficiency.

The development of the curved blade, epitomized by the tachi during the Heian period, marked a revolutionary shift. This curvature, known as sori, allowed for more effective draw cuts (hiki-giri) when drawn from the scabbard, especially from horseback. The momentum of the draw combined with the blade's curvature created a shearing action, allowing it to slice through targets with remarkable ease rather than simply chopping. This design was further refined into the katana during the Muromachi period, a shorter, more practical sword worn edge-up through the obi, facilitating even quicker draw cuts for infantry combat.

The table below outlines the major evolutionary stages of the Japanese sword and their respective advantages in cutting performance:

| Sword Type | Primary Period | Key Characteristics | Cutting Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chokuto | Nara Period (710-794) | Straight, single-edged, often unrefined forging. | Basic thrusting and chopping; limited shearing ability. |

| Tachi | Heian to Muromachi (794-1573) | Longer, pronounced curvature, worn edge-down (cavalry). | Optimized for draw cuts from horseback; excellent for slicing through unarmored targets. |

| Katana | Muromachi to Edo (1336-1868) | Shorter, less curvature than tachi, worn edge-up (infantry). | Quick draw and precise cutting; versatile for both slicing and thrusting in close quarters. |

| Wakizashi / Tanto | Muromachi to Edo (1336-1868) | Shorter companion swords; wakizashi (medium), tanto (dagger). | Close-quarters combat, thrusting into armor gaps, and supplementary cutting. |

7.2 The Samurai and Their Blades

The Japanese sword's reputation for cutting excellence is inextricably linked to the samurai, the warrior class who wielded them. For the samurai, the sword was not merely a tool but an extension of their spirit and a symbol of their status. Their rigorous training in martial arts such as kenjutsu (sword techniques) and iaijutsu (the art of drawing the sword) was designed to fully exploit the blade's inherent cutting capabilities.

On the battlefield, the samurai employed sophisticated techniques that capitalized on the sword's unique properties. The combination of a razor-sharp edge (ha), optimal blade geometry (niku, shinogi), and the spring-like flexibility of the spine allowed samurai to execute powerful, precise cuts. They were trained to target vulnerable points, such as joints, necks, or unarmored areas, to achieve decisive results. The draw cut (hiki-giri), where the blade is pulled across the target as it cuts, was a fundamental technique that maximized the sword's ability to sever flesh, bone, and even thin armor layers.

While often romanticized, the effectiveness of Japanese swords in combat was a practical reality. Historical accounts and records of tameshigiri (cutting tests, often performed on cadavers or bundles of straw) consistently demonstrated the blades' ability to cleanly sever multiple targets with a single, well-executed stroke. This combination of a technologically advanced blade, honed over centuries, and the masterful skill of the samurai who wielded it, solidified the Japanese sword's reputation as a weapon of supreme cutting power on the historical battlefield.

8. Preserving Cutting Excellence Through Maintenance

The exceptional cutting ability of a Japanese sword, forged through centuries of masterful craftsmanship, is not a static quality. It is a living attribute that requires diligent care and, at times, professional restoration to maintain its peak performance and historical integrity. Neglect can quickly degrade the blade, compromising its sharpness, structural soundness, and aesthetic appeal.

8.1 Proper Care and Storage

A Japanese sword is a delicate instrument, susceptible to environmental factors like humidity and temperature fluctuations, as well as the corrosive effects of human touch. Regular and meticulous maintenance is paramount to prevent rust, corrosion, and physical damage, ensuring the blade remains a formidable cutting tool and a preserved work of art.

8.1.1 Cleaning After Handling or Use

Even brief handling can leave behind oils and moisture from the skin, which are highly acidic and can initiate rust on the highly polished steel surface. After any contact, or especially after cutting tests like tameshigiri, immediate cleaning is essential. The traditional cleaning kit, often called an Oteire-Shu, includes specific tools for this purpose:

| Tool/Material | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Uchiko Powder Ball | A small silk ball containing very fine polishing powder (often derived from grinding stones). Used to gently abrade and lift old oil, dirt, and light rust from the blade surface. It leaves a fine, almost invisible layer that helps distribute the new oil. |

| Nuguigami (Rice Paper) | Soft, absorbent rice paper specifically designed for wiping the blade. Used to remove old oil and uchiko powder before applying new oil, and for initial wiping after use. |

| Choji Oil (Clove Oil) | A light, non-acidic mineral oil, often with a hint of clove scent, used to coat the blade. It creates a protective barrier against moisture and oxygen, preventing rust and corrosion. Only a very thin, even layer is required. |

| Brass Hammer (for mekugi) | Used to gently tap out the bamboo mekugi (retaining pin) when disassembling the sword for thorough cleaning or inspection. |

The process typically involves carefully removing the old oil and any residue with nuguigami, applying uchiko powder and gently rubbing it across the blade, wiping the powder off with fresh nuguigami, and finally applying a thin, even layer of choji oil. Never touch the polished surface of the blade (ha or jihada) with bare hands.

8.1.2 Optimal Storage Conditions

Beyond cleaning, the environment in which a Japanese sword is stored significantly impacts its preservation. Stable temperature and humidity are critical. High humidity is the primary catalyst for rust, while rapid temperature fluctuations can cause condensation on the blade. Swords should be stored in a dry, cool place, away from direct sunlight, air vents, or external walls where temperature and humidity swings are more pronounced.

For long-term storage, the sword should ideally be housed in a shirasaya. This is a plain, unlacquered wooden scabbard and handle set, typically made of magnolia wood. Unlike the lacquered and metal-fitted koshirae (the sword's full mounting for use or display), the shirasaya allows the wood to "breathe," naturally regulating moisture and preventing it from being trapped against the blade. The koshirae, while beautiful, is not designed for prolonged storage due to its less breathable materials which can trap moisture and accelerate rust.

Swords should generally be stored horizontally, with the edge (ha) facing slightly upwards to prevent undue pressure on the scabbard, which could eventually warp it or cause the blade to stick.

8.2 The Role of Professional Restoration

Despite the most diligent care, a Japanese sword may eventually require professional attention. This could be due to deep-seated rust, chips (hagire) in the edge, bends in the blade, or simply the natural degradation of the polish over many decades, obscuring the intricate details of the hamon and jihada. Professional restoration is a highly specialized field, crucial for preserving both the functional cutting excellence and the artistic value of these blades.

8.2.1 The Master Polisher (Togishi)

The togishi is arguably the most vital specialist in the preservation chain after the swordsmith. Their work is not merely about making the blade shiny; it is about revealing the true artistry and geometry of the blade, bringing out the subtle patterns of the steel (jihada) and the temper line (hamon) that define its unique character and cutting potential. A skilled polish also ensures the blade's proper cross-section (niku) and edge angle (ha) are maintained, which are fundamental to its cutting performance.

The polishing process is incredibly labor-intensive, involving multiple stages using a series of progressively finer water stones (toishi). Each stone brings out different characteristics of the steel. The final stages involve the use of small finger stones (hazuya and jizuya) and polishing powders to achieve the mirror-like finish on the ji (blade surface) and highlight the hamon.

A blade that has lost its polish (togire) will appear dull, its details obscured, and its cutting efficiency diminished. Only a professional togishi can restore it without damaging the blade's original form or removing too much precious steel.

8.2.2 Other Specialized Craftsmen

Beyond the polisher, a network of highly skilled artisans contributes to the comprehensive restoration of a Japanese sword and its mountings (koshirae):

- Saya-shi (Scabbard Maker): Crafts new saya (scabbards) or repairs existing ones, ensuring a perfect fit that protects the blade. They are also responsible for making custom shirasaya for long-term storage.

- Tsuka-maki-shi (Handle Wrapper): Re-wraps the handle (tsuka) with silk or cotton cord (ito), ensuring a tight, secure grip that is essential for effective cutting and preventing blade slippage during use.

- Kinko-shi (Metalworker): Specializes in the creation and repair of metal fittings such as the tsuba (handguard), fuchi (collar), kashira (pommel), and menuki (ornamental handle decorations).

- Shirasaya-shi (Wood Specialist for Shirasaya): Creates the custom-fitted plain wood scabbard and handle for long-term storage.

Entrusting a valuable Japanese sword to professional restorers is an investment in its longevity, ensuring that its historical significance, artistic beauty, and formidable cutting capabilities are preserved for future generations. These artisans possess generations of accumulated knowledge and precision, understanding the unique characteristics of each blade and applying traditional methods to maintain its excellence.

9. Summary

The unparalleled reputation of the Japanese sword, or katana, for its exceptional cutting ability is not attributed to a single factor but to a complex, harmonious interplay of centuries of metallurgical innovation, masterful craftsmanship, and refined design principles. From its very inception, every stage of a Japanese sword's creation is meticulously orchestrated to achieve superior sharpness, resilience, and effectiveness in severing targets.

At the core of this excellence lies Tamahagane steel, a unique, high-carbon material born from the traditional tatara furnace. Its inherent purity and the subsequent arduous folding and forging process (kitae) meticulously eliminate impurities while homogenizing carbon content and creating countless microscopic layers. This process results in a blade core that is both tough and flexible, encased by an outer layer capable of extreme hardness. This foundational material science is further elevated by the art of differential hardening, known as yakiba. Through the precise application of clay, the blade's edge (ha) is rapidly quenched to achieve Rockwell hardness levels that allow for razor sharpness, while the spine (mune) cools more slowly, remaining resilient and shock-absorbent. The visible result of this process, the distinct hamon line, is a testament to this ingenious balance, preventing the blade from shattering upon impact.

Beyond the material, the masterful blade geometry and design are critical for optimal cutting performance. The characteristic curvature (sori) of the Japanese sword is not merely aesthetic; it is engineered to facilitate the "draw cut," allowing the blade to slice through targets with minimal resistance. Furthermore, the intricate cross-section, including the ridgeline (shinogi) and varying thickness (niku), provides structural integrity while guiding the blade efficiently. The precise shape of the point (kissaki) and the acute edge angle (ha) are meticulously ground to maximize penetration and cutting efficiency, ensuring a clean, decisive cut.

The human element is indispensable. The Katanakaji, or master swordsmith, embodies generations of accumulated knowledge and unparalleled precision, overseeing every step from the selection of Tamahagane to the final shaping. Their skill ensures that the theoretical principles translate into a functional masterpiece. Equally vital is the Togishi, the expert polisher, who painstakingly reveals the blade's true potential. Through a multi-stage process, the Togishi not only enhances the blade's aesthetic beauty but also refines the edge to its ultimate sharpness, ensuring it can perform as intended.

The historical practice of Tameshigiri, or cutting tests, served as the ultimate proving ground for these blades, demonstrating their effectiveness against various targets and solidifying their reputation. This practical validation, combined with the symbiotic relationship between the Samurai warrior and their meticulously crafted blade, cemented the Japanese sword's legacy as a supreme cutting instrument on the battlefield.

Maintaining this cutting excellence requires diligent care and proper storage, safeguarding the blade against corrosion and damage. Professional restoration, when needed, ensures that these historical artifacts retain their functionality and aesthetic value for future generations.

9.1 Key Factors Contributing to Japanese Sword Cutting Excellence

| Key Element | Contribution to Cutting Excellence |

|---|---|

| Tamahagane Steel & Forging | Provides a unique balance of extreme hardness at the edge and underlying resilience throughout the blade via controlled carbon distribution and intricate layering. |

| Differential Hardening (Yakiba) | Creates a razor-sharp, durable cutting edge (ha) while maintaining a flexible, shock-absorbing spine (mune), significantly reducing the risk of breakage during impact. |

| Masterful Blade Geometry | Optimized curvature (sori), cross-section (shinogi, niku), and point (kissaki) are meticulously designed to facilitate efficient draw cuts, minimize drag, and maximize penetration. |

| Katanakaji (Master Swordsmith) | Embodies centuries of inherited knowledge and unparalleled precision, ensuring the theoretical principles of blade design and metallurgy are perfectly executed. |

| Togishi (Expert Polisher) | Painstakingly refines the blade's edge to its ultimate sharpness, reveals its internal structure, and enhances its cutting efficacy and aesthetic beauty. |

| Tameshigiri (Cutting Tests) | Historically and presently validates the blade's practical performance against various targets, serving as the ultimate proof of its superior effectiveness. |

In essence, the Japanese sword's reputation as the world's best cutting instrument is a testament to a holistic approach where material science, artistic design, and human mastery converge. Each component, from the raw steel to the final polish, is optimized not just for sharpness, but for the dynamic forces involved in cutting, making it a pinnacle of edged weapon engineering.

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Related Articles

Leave a comment: