Discover the history and ritual of seppuku (harakiri), its connection to the samurai code of bushido, and the cultural context surrounding this practice. Explore the reasons behind seppuku, including atonement, protest, and junshi (following one's lord). Understand the ritual's evolution, variations, and its portrayal in popular culture.

1. The History of Seppuku and Harakiri

1.1 Origins and Evolution of the Ritual

Seppuku, also known as harakiri, is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. While both terms refer to the same act, seppuku carries more formal and ritualistic connotations, while harakiri is considered more colloquial. The practice emerged during the Heian period (794-1185) of Japanese history amongst the samurai class. Initially, seppuku was primarily performed on the battlefield by defeated warriors to avoid capture and ensure a honorable death. It allowed samurai to maintain control over their fate and demonstrate their courage and loyalty in the face of defeat.

1.2 Seppuku in the Sengoku Period (1467-1615)

The Sengoku period, an era of near-constant warfare, saw a significant rise in the practice of seppuku. During this time, seppuku evolved beyond battlefield suicide. It became a judicially sanctioned form of capital punishment for samurai who had committed offenses deemed worthy of death. It was considered a more honorable form of execution compared to other methods. Furthermore, seppuku was sometimes performed by samurai to demonstrate loyalty to their deceased lord, a practice known as junshi. This practice, while initially voluntary, often became expected and pressured.

1.3 Seppuku in the Edo Period (1603-1867)

The Edo period, a time of relative peace and stability, saw further codification and ritualization of seppuku. The practice became highly formalized, with strict procedures and etiquette governing its performance. While still used as a form of capital punishment, seppuku was also increasingly performed for reasons of atonement or protest. For example, a samurai might commit seppuku to atone for a perceived failure or to protest against the actions of a superior. The role of the kaishakunin, a second who would behead the individual performing seppuku to shorten their suffering, became firmly established during this period. The Edo period also saw the development of different forms of seppuku, each with its own specific rituals and significance.

| Period | Primary Reasons for Seppuku | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Heian Period (794-1185) | Avoiding capture in battle, honorable death | Emergence of the practice amongst samurai |

| Sengoku Period (1467-1615) | Battlefield suicide, judicially sanctioned execution, junshi (following one's lord in death) | Rise in frequency, evolving beyond battlefield practice |

| Edo Period (1603-1867) | Capital punishment, atonement, protest | Formalization and ritualization, establishment of the kaishakunin, development of different forms |

2. Bushido The Samurai Code

Bushido, often translated as "the way of the warrior," was the moral code of the samurai, a powerful warrior class in feudal Japan. It wasn't a formal written code like a legal document, but rather a set of principles and ideals that evolved over centuries, influenced by Zen Buddhism, Confucianism, and Shintoism. Bushido emphasized virtues like loyalty, honor, and self-sacrifice, shaping the samurai's life both on and off the battlefield.

2.1 The Seven Virtues of Bushido

While the specific virtues emphasized in Bushido varied over time and across different regions and clans, seven core tenets are commonly recognized:

| Virtue (Japanese) | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gi (義) | Justice, Righteousness | Doing what is right and just, even if it is difficult. A samurai was expected to have a strong sense of morality and to act with integrity in all situations. |

| Yu (勇) | Courage, Bravery | Facing danger and adversity with fortitude and without fear. Physical courage was essential, but Bushido also emphasized moral courage – the courage to stand up for what is right, even in the face of opposition. |

| Jin (仁) | Benevolence, Compassion | Showing kindness and compassion to others, even enemies. While samurai were fierce warriors, they were also expected to be compassionate and understanding. |

| Rei (礼) | Respect, Courtesy | Treating others with respect and courtesy, regardless of their social standing. This included observing proper etiquette and showing deference to elders and superiors. |

| Makoto or Shin (誠/信) | Honesty, Sincerity | Being truthful and sincere in words and actions. A samurai's word was considered their bond. |

| Meiyo (名誉) | Honor | Maintaining one's honor and reputation above all else. This was considered the most important virtue in Bushido, and a samurai would go to great lengths to protect their honor. |

| Chuugi (忠義) | Loyalty, Duty | Being loyal and devoted to one's lord and superiors. This unwavering loyalty was a cornerstone of the samurai code. |

2.2 How Bushido Influenced Seppuku

Bushido's emphasis on honor, loyalty, and self-sacrifice played a significant role in the practice of seppuku. Seppuku was seen as a way for a samurai to regain their honor if they had acted dishonorably, to demonstrate their loyalty by following their lord in death (junshi), or to protest against injustice. By willingly taking their own life in a ritualized manner, samurai demonstrated their adherence to Bushido's ideals, even in the face of death. The act of seppuku, when performed according to the rituals of Bushido, was not considered suicide in the conventional sense, but rather a form of self-sacrifice and an affirmation of the samurai's commitment to their code.

3. The Seppuku Ritual

3.1 The Role of the Kaishakunin

The kaishakunin played a crucial role in the seppuku ritual. This individual, typically a trusted friend or colleague of the person performing seppuku, was responsible for delivering the kaishaku, a swift decapitating blow intended to shorten the suffering of the individual and ensure a quick and honorable death. The kaishakunin needed to be a skilled swordsman to perform this act precisely and efficiently. A poorly executed kaishaku could cause further pain and dishonor. The selection of a kaishakunin was a significant honor, demonstrating deep trust and respect between the two individuals.

3.2 The Process of Seppuku

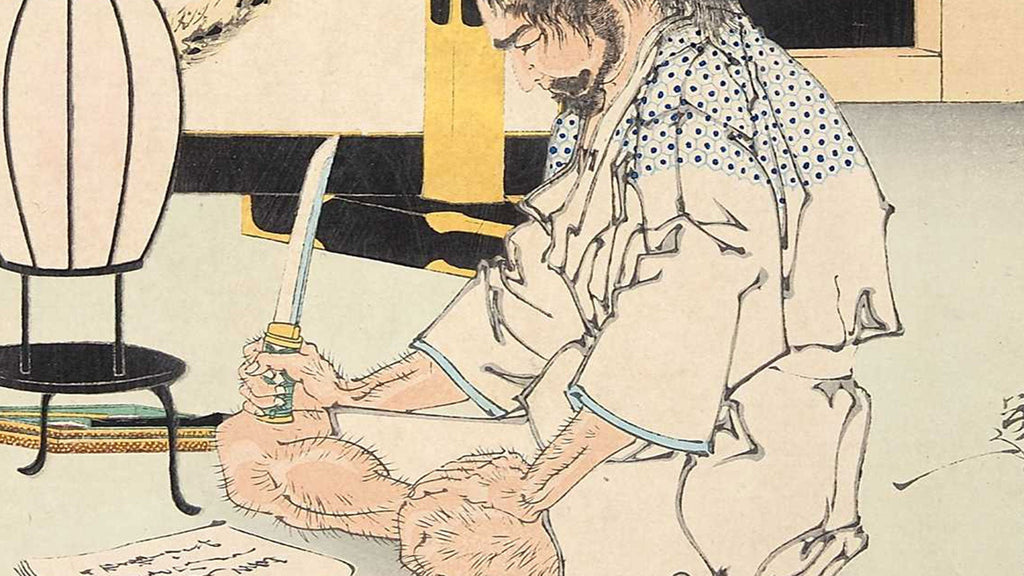

The seppuku ritual was highly formalized and imbued with symbolic meaning. The individual performing seppuku, dressed in white robes, would typically be presented with a ceremonial tantō (dagger), often placed on a sanbo (small stand). They would then write a death poem, a final expression of their thoughts and feelings. After consuming a ceremonial cup of sake, the individual would make a small incision in their abdomen, a symbolic gesture signifying the opening of their spirit. The kaishakunin would then perform the kaishaku, severing the head. In some instances, the individual would perform a deeper cut, but the kaishaku remained the intended method of ending the ritual.

3.3 Different Forms of Seppuku

There were several different forms of seppuku, each with its own specific ritual elements and significance. These variations often reflected the social status of the individual and the circumstances surrounding their death.

| Form of Seppuku | Description |

|---|---|

| Jumonji giri | A more extensive form of seppuku involving a horizontal cut after the initial vertical incision, creating a cross-shaped wound. |

| Funshi | Seppuku performed to demonstrate loyalty to one's lord, often following their death. This practice, known as junshi, was later banned. |

| Kanshi | Seppuku performed to protest an injustice or demonstrate strong disapproval of a superior's actions. |

It is important to note that the specific details of the seppuku ritual could vary depending on the time period, region, and the individual's social status. However, the core elements of the ritual, including the presence of the kaishakunin and the symbolic act of self-disembowelment, remained consistent.

4. Seppuku in Popular Culture

4.1 Seppuku in Literature and Film

Seppuku, often portrayed dramatically, has become a recurring theme in various forms of media, sometimes accurately, sometimes less so. Its depiction often serves as a narrative device to highlight themes of honor, sacrifice, and cultural differences. Examples of its portrayal can be found in:

| Medium | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Film | The Last Samurai (2003) | While fictionalized, the film depicts seppuku within the context of the Meiji Restoration and the decline of the samurai way of life. |

| Film | Seven Samurai (1954) | Though not centrally focused on seppuku, the film portrays the samurai code and hints at the possibility of ritual suicide under certain circumstances. |

| Film | Hara-Kiri (1962) | This Japanese film (also known as Seppuku) critically examines the societal pressures and hypocrisy surrounding the ritual. |

| Literature | Shogun by James Clavell (1975) | This novel offers a Western perspective on feudal Japan, including descriptions of seppuku and its cultural significance. |

| Literature | Taiko by Eiji Yoshikawa (1967) | This historical novel depicts the life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a prominent figure in Japanese history, and includes instances of seppuku within the narrative. |

4.2 Misconceptions and Sensationalism

Popular culture often simplifies or exaggerates aspects of seppuku, leading to several misconceptions. It's crucial to differentiate between dramatic portrayals and the historical reality:

- Overemphasis on the Gruesomeness: While undoubtedly a violent act, popular culture sometimes fixates on the graphic nature of seppuku, potentially overshadowing its cultural and historical context.

- Romanticized View of the Samurai: The samurai are often romanticized as noble warriors adhering strictly to bushido. While honor was important, the reality of samurai life was more complex and nuanced.

- Ignoring the Socio-Political Context: Seppuku was not always a freely chosen act. Social pressure, political maneuvering, and coercion played a significant role in many instances.

- Oversimplification of Bushido: Bushido is often portrayed as a monolithic code. In reality, its interpretation and application varied across time and different samurai clans.

- Conflation with Harakiri: While the terms are often used interchangeably, some scholars argue that subtle distinctions exist between "seppuku" and "harakiri" in terms of formality and social context.

By understanding these potential pitfalls, we can appreciate the complexities of seppuku and its representation in popular culture while maintaining a critical perspective on its historical accuracy.

5. Reasons for Seppuku

5.1 Seppuku as a Form of Atonement

Seppuku could be performed as a form of self-punishment for perceived failures or transgressions, allowing a samurai to restore their honor and avoid the disgrace of execution by another. This act demonstrated a strong sense of responsibility and adherence to the samurai code of Bushido. It was considered a way to atone for bringing shame upon oneself, one's family, or one's lord.

5.2 Seppuku as a Form of Protest

In some cases, seppuku was used as a powerful form of protest against unjust actions by superiors or the government. By taking their own lives, samurai could express their dissent and draw attention to the perceived injustice. This form of seppuku often carried significant political weight and could serve as a catalyst for change or at least as a powerful indictment of the status quo. One famous example is the seppuku of 47 ronin following their lord Asano Naganori's forced seppuku.

5.3 Seppuku to Follow One's Lord (Junshi)

Junshi, meaning "following in death," was the practice of retainers committing seppuku upon the death of their lord. This act was seen as the ultimate expression of loyalty and devotion. It was particularly prevalent during the Sengoku period but became increasingly restricted during the Edo period due to concerns about social stability. Junshi highlighted the intense bond between a lord and their samurai and the importance of loyalty within the feudal system.

| Reason | Description | Bushido Value |

|---|---|---|

| Atonement | Self-punishment for perceived failures or transgressions to restore honor. | Responsibility, Honor |

| Protest | A powerful statement against unjust actions by superiors. | Justice, Courage |

| Junshi (Following One's Lord) | An act of ultimate loyalty and devotion upon the death of one's lord. | Loyalty, Devotion |

While these are the most common reasons, seppuku could also be performed under other circumstances, such as being ordered by one's lord as a form of capital punishment or to avoid capture in battle. The act of seppuku, regardless of the reason, was deeply intertwined with the samurai code of Bushido and its emphasis on honor, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. Understanding the various motivations behind seppuku offers valuable insight into the complex social and cultural landscape of samurai Japan.

6. Summary

Seppuku (also known as harakiri), a form of ritual suicide, remains a complex and often misunderstood aspect of Japanese history and the samurai warrior culture. Strongly tied to the samurai code of bushido, seppuku was more than just a form of taking one's own life; it was a deeply symbolic act governed by strict rituals and imbued with cultural meaning.

This practice evolved over centuries, from its origins as a battlefield practice to a highly ritualized act performed for a variety of reasons. During the Sengoku and Edo periods, seppuku became increasingly codified, reflecting the evolving social and political landscape of Japan.

Bushido, the samurai code, heavily influenced the practice of seppuku. The seven virtues of bushido—gi (justice), yu (courage), jin (benevolence), rei (respect), makoto/shin (honesty), meiyo (honor), and chuugi (loyalty)—provided the ethical framework within which seppuku was understood and justified. A samurai might perform seppuku to atone for perceived failures, to protest injustice, or to follow their lord in death (junshi).

The seppuku ritual itself was highly formalized, often involving a kaishakunin, a second who would decapitate the individual performing seppuku to shorten their suffering and ensure a swift and honorable death. Different forms of seppuku existed, varying in the specific method and instruments used.

| Term | Meaning | Connection to Seppuku |

|---|---|---|

| Bushido | "Way of the Warrior"; the samurai code of conduct | Provided the ethical framework for seppuku |

| Kaishakunin | "Second"; the individual who decapitates the person performing seppuku | Ensured a swift and honorable death |

| Junshi | Following one's lord in death | A common reason for performing seppuku |

| Sengoku Period | Period of warring states in Japan (1467-1615) | Saw the widespread practice of seppuku on the battlefield |

| Edo Period | Period of relative peace and stability in Japan (1603-1867) | Seppuku became increasingly ritualized |

While seppuku continues to be depicted in popular culture, it is crucial to understand the historical context and cultural nuances surrounding this practice to avoid misconceptions and sensationalism. Seppuku represents a complex intersection of samurai culture, the bushido code, and the social and political realities of historical Japan. It serves as a stark reminder of the importance of honor, loyalty, and sacrifice in the samurai worldview.

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Related Articles

Leave a comment: