Explore Yukio Mishima's life, his embrace of the Bushido code, and the profound reasons behind his ritualistic harakiri. Understand his critique of modern Japan and the enduring legacy of his dramatic final act.

1. Understanding Yukio Mishima: A Literary and Political Figure

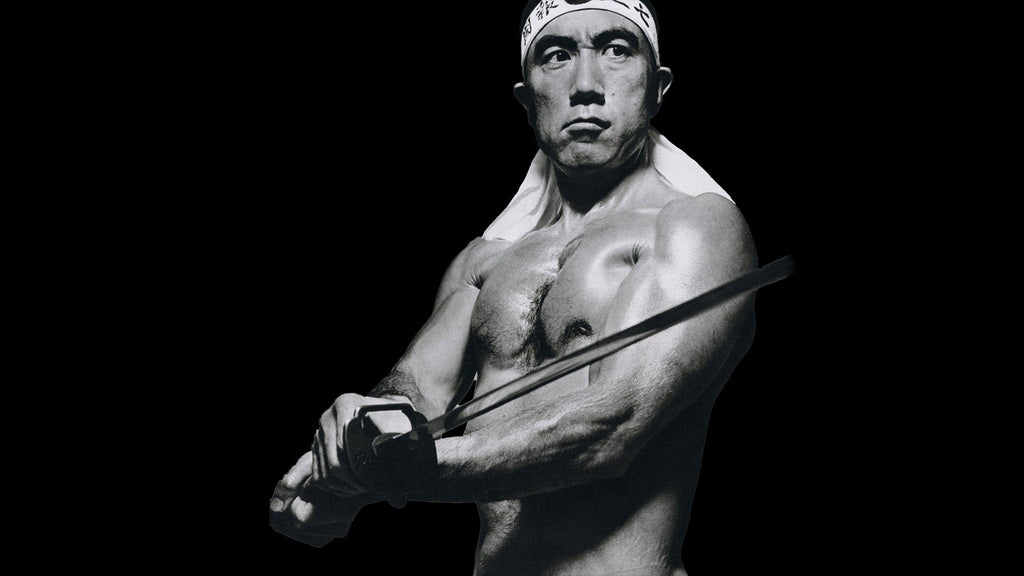

Yukio Mishima, born Kimitake Hiraoka, remains one of the most enigmatic and controversial figures in 20th-century Japanese literature and politics. Celebrated for his prolific and diverse literary output, which earned him multiple nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Mishima was equally known for his fervent nationalism, traditionalist views, and the dramatic, ritualistic nature of his death. To comprehend the motivations behind his final act of harakiri, it is essential to first delve into his formative years, intellectual development, and the societal landscape of post-war Japan that profoundly shaped his worldview.

1.1 Early Life and Literary Beginnings

Born in Tokyo on January 14, 1925, Kimitake Hiraoka's childhood was marked by a strict upbringing under his paternal grandmother, Natsuko, who largely isolated him from other children. This period of confinement fostered a rich inner world and an early inclination towards literature and the arts. Despite a delicate constitution in his youth, his intellect was undeniable. He attended the prestigious Gakushuin (Peers' School), an elite institution where he distinguished himself academically and began to explore his literary talents.

His literary career commenced remarkably early. At the age of 19, he published his first significant work, Hanazakari no Mori (Forest in Full Bloom), a collection of short stories, under the pseudonym Yukio Mishima. This pen name, adopted to conceal his literary pursuits from his family, would soon become synonymous with a unique voice in Japanese letters. Mishima's early works often explored themes of beauty, death, and the complexities of human desire, frequently with a lyrical and evocative prose style.

His breakthrough came with the 1949 novel Kamen no Kokuhaku (Confessions of a Mask), a semi-autobiographical work that candidly explored his struggles with identity, repressed homosexuality, and a profound fascination with death and violence. The novel's raw honesty and psychological depth immediately established him as a major literary force in post-war Japan. From this point, Mishima's career flourished, producing a vast body of work that included novels, plays, essays, and short stories, cementing his reputation as one of Japan's most important writers.

| Year | Title (English) | Title (Japanese) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | Forest in Full Bloom | Hanazakari no Mori | First significant publication under the pseudonym "Yukio Mishima," showcasing early literary talent. |

| 1949 | Confessions of a Mask | Kamen no Kokuhaku | Breakthrough novel, semi-autobiographical, exploring themes of identity, desire, and death, establishing his literary prominence. |

| 1950 | Thirst for Love | Ai no Kawaki | A psychological novel exploring destructive passion and the dark side of human relationships. |

| 1951 | Forbidden Colors | Kinjiki | A controversial novel further exploring themes of homosexuality, societal hypocrisy, and aestheticism. |

1.2 Philosophical and Aesthetic Influences

Mishima's intellectual and artistic development was shaped by a rich tapestry of influences, blending classical Japanese aesthetics with Western philosophical and literary traditions. He was deeply immersed in classical Japanese literature, Noh theater, and Kabuki, which instilled in him a profound appreciation for form, ritual, and the tragic beauty inherent in the ephemeral nature of life (mono no aware).

Simultaneously, Mishima avidly consumed Western literature and philosophy. Figures such as Oscar Wilde, Thomas Mann, and Rainer Maria Rilke influenced his aestheticism and romantic sensibility. Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy, particularly the concept of the "will to power" and the glorification of strength and self-overcoming, resonated deeply with Mishima's growing fascination with physical perfection and heroic ideals.

A pivotal aspect of Mishima's philosophy was his obsession with the body and masculinity. After a sickly youth, he embarked on an intense regimen of bodybuilding and martial arts (kendo, karate) in his late twenties. This was not merely a physical pursuit but a philosophical one, documented in his seminal non-fiction work, Taiyō to Tetsu (Sun and Steel). In this book, Mishima articulated his belief that the body was intrinsically linked to the spirit, and that physical discipline was essential for artistic and spiritual expression. He saw the body as a temple, a tool for achieving an idealized self, and a means to resist the perceived spiritual decay of modern Japan.

1.3 Post-War Japan and Mishima's Disillusionment

The backdrop against which Mishima's philosophy evolved was the dramatic transformation of Japan following its defeat in World War II. The American occupation brought about sweeping changes, including a new democratic constitution, economic reforms, and a concerted effort to dismantle Japan's militaristic past. While many Japanese embraced these changes, Mishima viewed them with profound skepticism and growing disillusionment.

He perceived a catastrophic erosion of traditional Japanese values and the national spirit. For Mishima, the post-war era represented a fundamental betrayal of Japan's heritage, characterized by the abandonment of the Emperor's divine status, the decline of the samurai ethic (Bushido), and a pervasive shift towards materialism and Western consumerism. He lamented what he saw as the feminization and intellectualization of Japan, believing the nation had lost its unique cultural identity and its warrior soul.

Mishima was particularly critical of the pacifist ideals that permeated post-war Japanese society, viewing them as a sign of weakness and a departure from the heroic virtues he admired. This deep-seated discontent fueled his increasingly radical political views and his fervent desire to restore what he believed was Japan's true essence and imperial sovereignty. His literary works, even those seemingly unrelated to politics, often subtly reflected this underlying anxiety about Japan's future and its perceived loss of a glorious past, setting the stage for his eventual dramatic political activism.

2. The Bushido Code: Principles of the Warrior Way

2.1 Origins and Evolution of Bushido

The term Bushido, literally "the way of the warrior," refers to the unwritten moral code and philosophy that guided the samurai, the warrior class of feudal Japan. While its roots can be traced back to the Kamakura period (1185-1333) with the rise of the samurai, Bushido was not a formalized written code in its early stages but rather a set of principles passed down through generations.

Its development was profoundly influenced by a synthesis of various philosophical and religious traditions:

- Zen Buddhism: Contributed to the samurai's stoicism, discipline, and acceptance of death. The practice of meditation fostered mental clarity and focus, crucial for a warrior.

- Shintoism: Instilled loyalty to the emperor and the homeland, reverence for nature, and a sense of purity and ritual.

- Confucianism: Provided the ethical framework, emphasizing loyalty to one's lord, filial piety, righteous conduct, and the importance of education and moral integrity.

Over centuries, these influences coalesced into a distinct code of conduct. While never codified into a single document during the height of the samurai era, its principles were reflected in various historical accounts, family precepts, and martial arts teachings. Later, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, works like Nitobe Inazō's Bushido: The Soul of Japan played a significant role in popularizing and formalizing Bushido for a Western audience, often emphasizing its ethical and spiritual dimensions.

2.2 Key Virtues of Bushido: Honor, Loyalty, and Self-Discipline

At the heart of Bushido lay a set of virtues that dictated a samurai's behavior, both on and off the battlefield. These principles were not merely abstract ideals but practical guidelines for living a life of integrity, courage, and purpose. Honor (Meiyo) was paramount, often considered more valuable than life itself, leading to a strong emphasis on maintaining one's reputation and dignity.

The core virtues of Bushido include:

| Virtue (Japanese) | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 義 (Gi) | Rectitude / Righteousness | The ability to make decisions based on what is morally right, even in the face of adversity. It is the most stringent virtue, ensuring justice and fairness. |

| 勇 (Yū) | Courage | Not just physical bravery, but heroic courage that involves living righteously and facing challenges with resolve. It is about acting with intelligence and strength. |

| 仁 (Jin) | Benevolence / Compassion | A deep sense of empathy and compassion towards others, especially the weak or less fortunate. A true warrior was expected to show mercy and kindness. |

| 礼 (Rei) | Respect / Politeness | Treating others with utmost courtesy and respect, regardless of their status. This virtue underscored the importance of proper etiquette and social harmony. |

| 誠 (Makoto) | Honesty / Sincerity | Speaking the truth and acting with integrity. A samurai's word was his bond, and deception was considered dishonorable. |

| 名誉 (Meiyo) | Honor | The supreme virtue, signifying one's reputation and dignity. Losing honor was often considered worse than death, and it dictated many samurai actions, including ritual suicide. |

| 忠義 (Chūgi) | Loyalty | Unwavering devotion and allegiance to one's lord, family, and country. This was a cornerstone of the feudal system and a samurai's primary duty. |

| 自制 (Jisei) | Self-Control / Self-Discipline | The ability to control one's emotions, desires, and impulses. This stoicism was crucial for maintaining composure in battle and making rational decisions. |

These virtues fostered a warrior ethos that valued not only martial prowess but also moral uprightness, intellectual cultivation, and a profound sense of duty. The concept of giri (duty or obligation) often intertwined with these virtues, guiding a samurai's actions and choices, sometimes leading to tragic dilemmas between personal desires and societal expectations.

2.3 Bushido's Resurgence in Modern Japan

While the samurai class was abolished with the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the principles of Bushido did not vanish. Instead, they underwent a significant transformation and resurgence, adapting to new political and social landscapes. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bushido was reinterpreted and promoted as a national ideology, particularly during periods of rising nationalism and militarism.

- National Identity: Bushido was leveraged to foster a sense of national unity, discipline, and loyalty to the Emperor, becoming a core component of moral education in schools and military training.

- Post-War Re-evaluation: Following Japan's defeat in World War II, Bushido's association with militarism led to a period of decline and critical re-evaluation. Many viewed it as a dangerous ideology that had contributed to the nation's wartime atrocities.

-

Contemporary Relevance: Despite its complex history, Bushido has experienced a nuanced resurgence in modern Japan. Its emphasis on discipline, loyalty, and self-improvement finds echoes in various aspects of contemporary society:

- Business Ethics: Concepts of loyalty to the company, diligence, and integrity are often framed in terms of modern Bushido.

- Martial Arts: Traditional Japanese martial arts like Kendo, Judo, and Aikido continue to teach and embody Bushido's virtues of respect, discipline, and perseverance.

- Popular Culture: Elements of Bushido are frequently explored in Japanese literature, film, manga, and anime, often romanticizing the samurai ideal or examining its moral complexities.

For figures like Yukio Mishima, Bushido represented a vital link to Japan's traditional values and a spiritual antidote to what he perceived as the corrupting influences of Westernization and materialism in post-war Japan. His embrace of the warrior ideal was deeply rooted in his interpretation of these enduring principles.

3. Harakiri and Seppuku: The Ritual of Honorable Death

In the lexicon of Japanese martial tradition, few terms evoke as much solemnity and profound cultural significance as harakiri and seppuku. Often used interchangeably in common parlance, these terms refer to the ritualistic act of self-disembowelment, a practice deeply intertwined with the samurai code and the pursuit of honor. While "harakiri" (腹切り) literally means "belly cutting" and is the more colloquial term, "seppuku" (切腹) is the more formal and respectful term, using the same kanji characters but in a different order, emphasizing the ritualistic aspect.

3.1 Historical Context and Purpose of Seppuku

The origins of seppuku can be traced back to the feudal era of Japan, particularly among the samurai class, emerging prominently during the Sengoku period (15th-17th centuries). It was not merely a form of suicide but a highly ritualized act with specific purposes, serving as the ultimate expression of honor, loyalty, and atonement. Samurai might perform seppuku for various reasons:

- To Avoid Capture: Rather than face the ignominy of capture by an enemy, which could lead to torture or public execution, a samurai would choose seppuku to preserve his honor and that of his family line.

- To Atone for Failure or Crime: If a samurai committed a serious offense or failed in a duty, seppuku was often the prescribed punishment or a voluntary act to take responsibility and restore honor, even in death.

- To Protest or Express Disagreement: On rare occasions, a samurai might perform seppuku as a powerful form of protest against a lord's unjust actions or policies, hoping to influence a change.

- To Follow One's Lord in Death (Junshi): Known as junshi (殉死), this practice involved a retainer committing seppuku upon the death of their lord, demonstrating ultimate loyalty. While later discouraged and even outlawed, it was a significant aspect of early samurai culture.

- As a Form of Capital Punishment: For samurai, seppuku was considered a more honorable form of execution than beheading by an executioner, allowing the condemned to die with dignity and retain their warrior status.

This practice underscored the samurai's profound belief that honor was more valuable than life itself, and that a controlled, dignified death was preferable to a life lived in shame.

3.2 The Ritualistic Process and Its Symbolism

Seppuku was a meticulously choreographed ritual, performed with great solemnity and precision. The process was designed to demonstrate the samurai's courage, self-control, and unwavering resolve in the face of death. Key elements included:

- Preparation: The samurai would typically purify himself by taking a ritual bath, dress in a white kimono (the color of purity and death), and often compose a jisei (辞世), a death poem, expressing his final thoughts.

- The Weapon: A short sword, usually a tanto or wakizashi, was placed before him, sometimes on a special tray.

- The Act: The samurai would traditionally plunge the blade into the left side of his abdomen, draw it across to the right, and then often make an upward cut. This act, while excruciating, was meant to demonstrate incredible willpower.

- The Kaishakunin: Central to the ritual was the kaishakunin (介錯人), a trusted second who stood ready to deliver a swift, decapitating blow with a katana the moment the samurai began the disembowelment. The purpose of the kaishakunin was to ensure a quick and merciful end, preventing prolonged suffering and preserving the dignity of the act. The timing of this blow was crucial and required immense skill and sensitivity.

The symbolism embedded in seppuku is profound. The abdomen, or hara (腹), was traditionally believed to be the seat of the soul, emotions, and will in Japanese culture. Therefore, opening the abdomen was seen as revealing one's true spirit and sincerity, proving one's courage and purity of intent to the onlookers and the gods. It was a final, powerful declaration of one's inner character.

3.3 Seppuku in Japanese Culture and Literature

Though the practice of seppuku was officially outlawed in Japan in 1873, its legacy continues to resonate deeply within Japanese culture and literature. It remains a powerful symbol of the samurai spirit, embodying the ultimate commitment to honor, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. It is often presented as the epitome of Bushido's core tenets.

The ritual has been immortalized in countless historical accounts, legends, and artistic works. One of the most famous examples is the story of the Forty-Seven Ronin (Chūshingura), where the loyal retainers avenge their master's death and then collectively commit seppuku, becoming enduring heroes in Japanese folklore. This tale, adapted into numerous plays, films, and novels, reinforces the cultural narrative of seppuku as an honorable and heroic act.

| Term | Japanese Script | Meaning/Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Harakiri | 腹切り | Colloquial term for self-disembowelment; literally "belly cutting." |

| Seppuku | 切腹 | Formal, respectful term for the ritualistic act of honorable self-disembowelment. |

| Kaishakunin | 介錯人 | The "second" who performs the decapitation to ensure a swift and merciful death during seppuku. |

| Jisei | 辞世 | A death poem, often composed by the samurai before performing seppuku. |

| Junshi | 殉死 | The act of a retainer committing seppuku upon the death of their lord, demonstrating ultimate loyalty. |

| Hara | 腹 | The abdomen, traditionally considered the seat of the soul, emotions, and will. |

| Tanto / Wakizashi | 短刀 / 脇差 | Short swords used for the act of disembowelment. |

Despite its violent nature, seppuku is not viewed solely as an act of despair but often as a courageous demonstration of spiritual strength and adherence to an ethical code. Its enduring presence in the cultural imagination speaks to the profound value placed on honor, duty, and self-mastery within traditional Japanese thought, elements that would deeply influence figures like Yukio Mishima.

4. Mishima's Embrace of Bushido and the Warrior Ideal

4.1 The Aesthetic of Death and Mishima's Philosophy

Yukio Mishima’s profound fascination with death was not morbid but deeply intertwined with his aesthetic philosophy and his interpretation of the Bushido code. For Mishima, the concept of a beautiful death, particularly one chosen voluntarily and honorably, represented the pinnacle of human existence and artistic expression. He viewed the physical body as a transient vessel, and its ultimate perfection could only be realized through an act of supreme will, often culminating in sacrifice. This belief resonated strongly with the samurai ideal of facing death without fear, understanding life's impermanence, and prioritizing honor above all else.

Mishima engaged in rigorous physical training, including bodybuilding and martial arts, not merely for health but as a means to sculpt his body into a work of art, a vessel prepared for a decisive, meaningful end. He believed that the true essence of beauty lay in the tension between life and death, and that physical perfection, when combined with the readiness for sacrifice, achieved a transcendent quality. His literary works, such as Confessions of a Mask and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, often explored themes of self-destruction, purity, and the pursuit of an absolute aesthetic, frequently through violent or extreme acts. This philosophical stance led him to advocate for a "pure act" – a decisive, unmediated action that bypassed intellectualization and embraced a raw, unadulterated commitment to one's ideals, even if it meant self-annihilation.

4.2 The Shield Society Tatenokai and Its Purpose

Mishima’s philosophical convictions were not confined to his literary output; they materialized in his political activism, most notably through the formation of the Tatenokai, or Shield Society. Established in 1968, this private paramilitary group was a direct manifestation of Mishima’s desire to embody the warrior ideal in modern Japan and to actively counter what he perceived as the nation's spiritual decline. The Tatenokai comprised a small, hand-picked group of young, right-wing students who shared Mishima's fervent nationalism and his disillusionment with post-war Japan.

The primary purpose of the Tatenokai was multifaceted:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Ideological Foundation | To uphold and defend the Emperor (Tennō) as the spiritual and cultural heart of Japan, believing him to be the embodiment of national identity, rather than merely a symbolic figure. |

| Countering Decline | To resist the perceived moral decay, spiritual emptiness, and loss of traditional Japanese values that Mishima attributed to the pervasive influence of Westernization and the post-war pacifist constitution. |

| Paramilitary Training | To serve as a private militia, receiving training from the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) to develop military discipline and skills. Their stated aim was to be a last line of defense in the event of a communist uprising or an external threat, supporting the JGSDF. |

| Embodiment of Bushido | To live by and demonstrate the principles of the Bushido code in a contemporary setting, emphasizing honor, loyalty, self-discipline, and a readiness for self-sacrifice in service of the nation. |

Mishima personally led the Tatenokai, overseeing their training, delivering ideological lectures, and actively participating in their activities. The society was a tangible symbol of his commitment to a revived nationalist spirit and his belief that a return to the warrior ethos was essential for Japan's future.

4.3 Mishima's Critique of Post-War Japan and Westernization

Yukio Mishima was a vocal and passionate critic of post-World War II Japan, viewing the nation's trajectory with profound disillusionment and despair. His critique centered on what he perceived as a fundamental loss of Japanese identity, pride, and spiritual vitality, largely due to the imposition of a Westernized democratic framework and the abandonment of traditional values.

His primary target was the post-war constitution, particularly Article 9, which renounced Japan's right to maintain military forces and wage war. Mishima saw this as an emasculation of the nation, stripping it of its historical warrior spirit and leaving it vulnerable and without a true sense of purpose. He vehemently advocated for a revision or outright abolition of this "pacifist" constitution, believing it prevented Japan from reclaiming its rightful place as a sovereign and self-respecting nation.

Beyond the constitution, Mishima railed against the pervasive influence of Western culture, which he believed was eroding traditional Japanese aesthetics, spiritual depth, and the unique national character. He saw the influx of Western democratic ideals, consumerism, and popular culture as leading to a society that was:

- Spiritually Empty: Lacking the profound spiritual connection and aesthetic appreciation that characterized pre-war Japan.

- Materialistic: Obsessed with economic prosperity and comfort at the expense of honor, duty, and sacrifice.

- Complacent: Content with its new-found peace and prosperity, forgetting the sacrifices of its ancestors and losing its will to defend its heritage.

- Disconnected from its Past: Forgetting the Bushido code, the Emperor's divine status, and the samurai tradition that had historically defined Japanese identity.

Mishima longed for a return to a more traditional, heroic Japan, where the Emperor was revered as a living deity, and the warrior spirit of Bushido guided the nation's ethos. His writings and actions were a desperate plea for Japan to awaken from what he saw as a spiritual slumber and reclaim its authentic self, even if it required a violent, shocking act to ignite that reawakening.

5. The Ichigaya Incident: Mishima's Final Stand

On November 25, 1970, Yukio Mishima executed a meticulously planned act of defiance and self-sacrifice that would forever be etched into Japanese history. This event, known as the Ichigaya Incident, was not merely a suicide but a final, dramatic statement against what he perceived as the moral decay and spiritual emptiness of post-war Japan. It was the culmination of his philosophical convictions, his artistic expressions, and his deep-seated disillusionment.

5.1 Preparations and The Coup Attempt

For months, if not years, Mishima had been preparing for this ultimate act. His private army, the Shield Society (Tatenokai), composed of young, nationalist students, was ostensibly formed for self-defense and traditional martial arts training, but it also served as the instrument for his final political theater. The target of his coup attempt was the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) Eastern Army Headquarters in Ichigaya, Tokyo, a symbolic bastion of the nation's military power.

On the fateful day, Mishima, accompanied by four key members of the Shield Society—Masakatsu Morita, Hiroyasu Koga, Masayoshi Koga, and Kenji Ogawa—arrived at the Ichigaya base under the pretext of a routine visit to General Kanetoshi Mashita, the commanding general. Once inside the general's office, the group barricaded the doors and took General Mashita hostage, demanding that the soldiers of the JSDF assemble in the parade ground below to hear Mishima's address.

The initial phase of the coup relied on surprise and intimidation. Mishima had hoped that his dramatic action would ignite a spark of nationalistic fervor within the JSDF, leading them to rise up against the pacifist constitution and restore the Emperor's divine authority. However, the soldiers, confused and disbelieving, remained largely unresponsive, viewing the situation as an inexplicable and bizarre spectacle rather than a genuine call to arms.

5.2 The Speech and The Call to Action

From a balcony overlooking the parade ground, Mishima delivered his impassioned speech to approximately 1,000 JSDF soldiers. His voice, amplified by a loudspeaker, boomed across the compound, but it was largely drowned out by the noise of helicopters and the jeers of the bewildered troops. Mishima's address was a desperate plea for the JSDF to reject the post-war constitution, which he saw as having stripped Japan of its national identity and martial spirit. He implored them to reassert the true spirit of Bushido and restore the Emperor's rightful place as a living deity, rather than a mere symbol.

He criticized the JSDF for their perceived subservience to foreign powers and their failure to embody the traditional warrior ethos. He called for a constitutional revision that would allow Japan to regain its military sovereignty and honor. However, his words failed to resonate. The soldiers, far from being inspired, responded with ridicule and indifference, shouting for him to come down. This hostile reception confirmed the failure of his audacious gamble to incite a nationalist uprising.

5.3 The Act of Seppuku and Its Aftermath

5.3.1 The Ritual Execution

Upon realizing the futility of his speech, Mishima retreated back into General Mashita's office. There, in a final act of adherence to the ancient warrior code, he prepared to perform seppuku, the ritual suicide by disembowelment. This was not a spontaneous act but the culmination of his life's philosophy, a dramatic and aestheticized death that he had contemplated and written about extensively.

Mishima knelt on the floor, donned a white headband, and plunged a ceremonial dagger into his abdomen. His chosen kaishakunin, Masakatsu Morita, was tasked with the beheading, a swift and clean cut to end the suffering and ensure an honorable death. However, Morita, overwhelmed by the moment, failed to deliver the fatal blow effectively, striking Mishima's shoulder twice. It was then that Hiroyasu Koga, another Shield Society member, stepped in and successfully performed the decapitation, bringing Mishima's life to an end.

Immediately afterward, Morita also performed seppuku, with Koga again acting as his kaishakunin. The remaining two members of the Shield Society, Masayoshi Koga and Kenji Ogawa, surrendered to the authorities.

| Key Figures in the Ichigaya Incident | Role | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Yukio Mishima | Leader of the coup attempt, primary performer of seppuku | Died by seppuku |

| Masakatsu Morita | Shield Society member, Mishima's first kaishakunin, then performed seppuku | Died by seppuku |

| Hiroyasu Koga | Shield Society member, Mishima's and Morita's successful kaishakunin | Arrested, imprisoned |

| Masayoshi Koga | Shield Society member | Arrested, imprisoned |

| Kenji Ogawa | Shield Society member | Arrested, imprisoned |

| General Kanetoshi Mashita | Commanding General of JSDF Eastern Army Headquarters | Hostage, released unharmed |

5.3.2 Public Reaction and Media Coverage

The news of Mishima's seppuku sent shockwaves across Japan and the world. The act, so anachronistic in modern times, was met with a mixture of bewilderment, horror, and a degree of grudging admiration. Media outlets globally scrambled to cover the unprecedented event, attempting to make sense of a celebrated literary figure's violent and ritualistic death.

In Japan, the incident sparked intense debate. Many viewed Mishima's actions as the desperate act of a madman, an extremist out of touch with contemporary society. Others, particularly those on the political right, saw him as a tragic hero who had sacrificed himself for his nation's honor, a true embodiment of the Bushido spirit in an era that had forgotten it. His death forced a national introspection on identity, tradition, and the legacy of World War II.

The Ichigaya Incident remains one of the most dramatic and controversial events in modern Japanese history, cementing Mishima's legacy not just as a writer, but as a complex and enigmatic figure who chose a spectacular, violent end to convey his final message.

6. Legacy and Interpretation: The Enduring Impact of Mishima's Death

6.1 Mishima's Place in Japanese Literature and Politics

Yukio Mishima, born Kimitake Hiraoka, remains one of Japan's most celebrated and controversial literary figures. His prolific output spanned novels, plays, essays, and poetry, earning him three nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Works such as Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and the ambitious tetralogy The Sea of Fertility showcased his profound psychological insight, aesthetic sensibility, and mastery of language. His literary legacy is characterized by its exploration of themes like beauty, death, sexuality, identity, and the conflict between traditional Japanese values and post-war Westernization. He meticulously crafted a public persona that blurred the lines between art and life, culminating in his dramatic final act.

In the political sphere, Mishima was a staunch traditionalist and nationalist who lamented what he perceived as Japan's spiritual decline and abandonment of its imperial heritage following World War II. He advocated for a return to the Emperor's spiritual authority and a rearmament of Japan, forming his private militia, the Tatenokai (Shield Society), to embody his ideals. His political activism, though often dismissed as eccentric, was a serious and deeply felt critique of the post-war pacifist constitution and the perceived erosion of Japanese identity. His death, therefore, was not merely a personal tragedy but a highly publicized political statement that forced a deeply uncomfortable self-reflection upon the nation.

6.2 Debates Surrounding His Actions and Motivations

Mishima's ritual suicide at the Ichigaya Incident ignited a firestorm of debate that continues to this day, polarizing opinions both in Japan and internationally. Was his final act a genuine political protest, a calculated performance, or the tragic culmination of personal psychological struggles? Critics and admirers alike grapple with these questions:

- Political Act vs. Theatrical Performance: Many view his coup attempt as ill-conceived and destined to fail, leading some to interpret it as a meticulously staged, albeit deadly, piece of performance art designed to solidify his legacy. Others contend it was a desperate, sincere attempt to awaken Japan to its perceived spiritual crisis.

- Mental State and Intent: Speculation abounds regarding Mishima's psychological health. Was he driven by a deep-seated death wish, a desire for martyrdom, or an unwavering commitment to his ideological convictions? His fascination with death and violence, evident throughout his literary works, is often cited as evidence of a complex internal landscape.

- The "Last Samurai" vs. "Madman" Dichotomy: To some, Mishima embodied the ultimate samurai ideal, a man of honor willing to sacrifice his life for his beliefs and nation, standing against the tide of modernity. To others, he was an extremist, a deluded narcissist whose actions were irrational and dangerous.

- Aesthetic vs. Ideological Purity: His final act is often seen as the ultimate fusion of his aesthetic philosophy and political ideology. The dramatic setting, the carefully chosen uniform, and the ritualistic nature of his death underscore his belief in the **beauty of sacrifice and the purity of conviction**.

These debates highlight the enduring complexity of Mishima's character and the difficulty in neatly categorizing his motivations, which were undoubtedly a confluence of personal, artistic, and political forces.

6.3 The Symbolic Power of His Final Act

Mishima's seppuku on November 25, 1970, transcended a mere news event to become a powerful, enduring symbol in Japanese and global culture. It was an act designed to shock, to provoke, and to leave an indelible mark, and in that, it undeniably succeeded.

His death is widely interpreted as:

| Symbolic Interpretation | Meaning and Impact |

|---|---|

| A Rejection of Post-War Japan | Mishima's act was a **violent repudiation of the perceived spiritual emptiness, materialism, and Westernization** that he believed had corrupted post-war Japan. It was a final, desperate plea for a return to traditional values, national pride, and the martial spirit of Bushido. |

| The Embodiment of Bushido | For many, Mishima's seppuku was the ultimate expression of the Bushido code in a modern context. It represented honor, loyalty to the Emperor, and a willingness to die for one's beliefs, thus serving as a **stark reminder of a warrior ethos** that he felt Japan had forgotten. |

| An Artistic Statement | Given his lifelong obsession with death, beauty, and the fusion of art and life, his seppuku is often seen as his final, most dramatic work of art—a **carefully choreographed tragedy designed to perfect his life's narrative**. It was the ultimate aesthetic act, making his death inseparable from his literary and philosophical output. |

| A Prophetic Warning | For some, Mishima's act was a prophetic warning against the dangers of cultural amnesia and the loss of national identity. He foresaw a future where Japan's unique spirit would be diluted, and his death was a **desperate attempt to awaken his countrymen**. |

| A Figure of Contradiction | Mishima's legacy is marked by profound contradictions: a bodybuilder who embraced delicate aesthetics, a nationalist who admired Western literature, and a man who sought to restore traditional values through a shockingly modern act. His death perfectly encapsulated these paradoxes, making him an **enduring enigma in Japanese cultural history**. |

Ultimately, Yukio Mishima's final act of harakiri, steeped in the principles of Bushido, continues to resonate as a **profound and unsettling challenge to post-war Japanese society** and a powerful, if controversial, testament to one man's unwavering commitment to his ideals. His life and death remain a focal point for discussions on nationalism, identity, aesthetics, and the complex relationship between art and political action.

7. Summary

The life and dramatic death of Yukio Mishima encapsulate a profound exploration of traditional Japanese values, particularly the Bushido code, in stark contrast to the perceived decline of post-war Japan. A prolific and controversial literary and political figure, Mishima's journey was marked by a deep disillusionment with Westernization and a fervent desire to rekindle the spirit of ancient Japan. His philosophical and aesthetic influences were heavily rooted in a romanticized vision of the samurai warrior and an embrace of the aesthetic of death, which he saw as the ultimate expression of beauty and purity.

The Bushido code, the way of the warrior, served as the bedrock of Mishima's convictions. Originating from the samurai class, Bushido emphasizes virtues such as honor (gi), courage (yu), benevolence (jin), respect (rei), honesty (shin), loyalty (chū), and self-control (mei). Mishima believed that these principles, once central to Japanese identity, had been eroded, leading to a spiritual void. His critique of post-war Japan and its embrace of a pacifist, materialist existence was a direct call for a return to these martial and spiritual ideals. He embodied this conviction through his writing, his physical training, and the formation of the Shield Society (Tatenokai), a private militia dedicated to protecting the Emperor and traditional Japanese culture.

The ritual of harakiri, or seppuku, an honorable form of ritual suicide, stands as the tragic climax of Mishima's life. Historically, seppuku was performed by samurai to restore honor, avoid capture, or protest injustice, signifying an ultimate act of self-discipline and loyalty. Mishima viewed this act not merely as death, but as a profound statement—a final, defiant gesture against what he perceived as the spiritual death of his nation. His fascination with this ritual, evident in his literature, culminated in his own public act.

On November 25, 1970, Mishima executed the meticulously planned Ichigaya Incident. After seizing the headquarters of the Japan Self-Defense Forces in Ichigaya, he delivered a passionate, yet ultimately futile, speech to the gathered soldiers, urging them to rise up and restore the Emperor's power and Japan's martial spirit. Failing to incite a coup, Mishima then performed seppuku, assisted by his Shield Society members. This shocking act of ritual execution, broadcast globally, cemented his place as a figure of immense controversy and fascination.

Mishima's legacy remains complex and deeply debated. He is remembered as both a literary genius, a three-time Nobel Prize nominee, and a radical right-wing nationalist whose final act was a desperate, symbolic protest. His death continues to provoke discussions about Japanese identity, the clash between tradition and modernity, and the ultimate sacrifice for one's beliefs. His life, and particularly his final harakiri, serve as a powerful testament to his unwavering commitment to the Bushido code and his profound despair over the perceived loss of Japan's ancient soul.

| Key Element | Mishima's Connection and Significance |

|---|---|

| Yukio Mishima | A renowned author and political activist who became a symbol of resistance against post-war Japan's Westernization and perceived spiritual decline. His life culminated in a dramatic act of protest. |

| Bushido Code | The core philosophy that guided Mishima's life and actions, emphasizing honor, loyalty, self-discipline, and courage. He believed its revival was essential for Japan's national spirit. |

| Harakiri/Seppuku | The ritualistic honorable suicide performed by Mishima. For him, it was not merely an end but the ultimate expression of his convictions, a symbolic protest, and a final act of adherence to the warrior ideal. |

| Ichigaya Incident | The meticulously planned event on November 25, 1970, where Mishima attempted to incite a military coup before performing seppuku, marking his final stand and public statement. |

| Legacy | Mishima remains a polarizing figure whose death continues to spark debate about nationalism, tradition, modernity, and the role of the individual in shaping national identity. |

Want to buy authentic Samurai swords directly from Japan? Then TOZANDO is your best partner!

Related Articles

Leave a comment: